**TL;DR: Because of abundant cosmic material and gravitational dynamics in the early protoplanetary disk, multiple worlds were able to form around our Sun, giving rise to the rich variety of planets we see today.

How Stellar Disks Become Planetary Nurseries

The story begins with a nebula—a vast cloud of gas and cosmic dust left behind by older stars. This cloud contained hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements, which are the essential building blocks of planets.

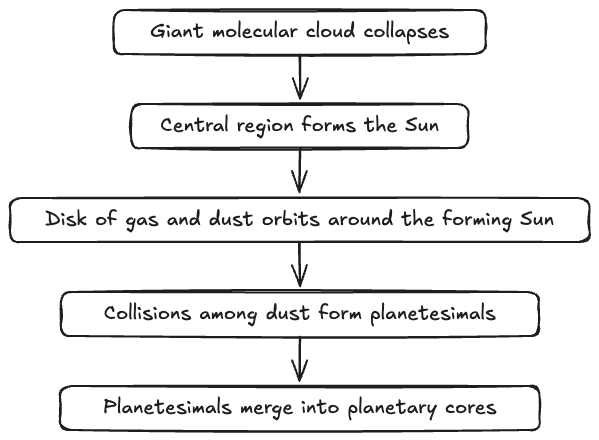

Over time, a region of the nebula began to collapse under its own gravity. Imagine taking a giant, fluffy blanket (the nebula) and gradually pulling in its corners until it becomes a tight, spinning bundle. In our solar system, that “bundle” became the Sun, surrounded by a rotating protoplanetary disk of leftover material.

As the disk swirled, collisions and clumping occurred among the dust grains within it, eventually creating larger “pebbles,” then “boulders,” and finally planetesimals (small, asteroid-like bodies). These planetesimals merged, shattered, and merged again, forging what would become the cores of planets.

Why So Much Material in One Place?

You might wonder why there was enough material for so many planets. The Sun formed at the center, pulling much of the gas inward. However, a significant amount of debris remained in orbit, never falling into the star. That leftover matter spread out in the disk, becoming the seeds of our eight known planets, as well as dwarf planets, asteroids, and countless smaller bodies.

If Earth were the size of a basketball, the total mass of the protoplanetary disk before the planets formed would be like a massive warehouse stacked high with basketballs—plenty of material to shape multiple worlds.

Diagram: The Protoplanetary Disk Formation

Diagram: How the solar system formed from a collapsing nebula

The Nebular Hypothesis and Its Lasting Influence

Scientists describe this process through the nebular hypothesis, proposed centuries ago and refined through modern data. It states that planetary systems emerge from a rotating disk of gas and dust around a nascent star. Our solar system’s multitude of planets can be traced back to the energetic swirling and sorting of these materials in the disk.

Because our nebula was relatively large, the Sun didn’t gobble up every speck of dust. Sizable amounts remained, allowing multiple planetary embryos to form. Had the original cloud been smaller, or if the star had been more voracious, we might have ended up with fewer planets.

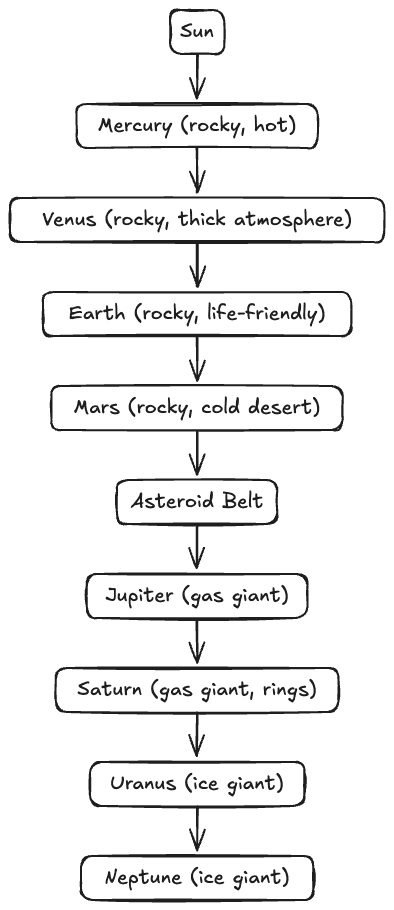

Inner Worlds vs. Outer Giants

One major reason we see such variety—and quantity—of planets is the temperature gradient in the protoplanetary disk. Near the Sun, it was far too hot for volatile substances like water and methane to remain solid. Only rocky materials (silicates and metals) could condense there, resulting in the terrestrial planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

Farther out, conditions were cooler, allowing ices and gases to remain stable. This region produced the gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn) and the ice giants (Uranus and Neptune). Because there was so much gas in the outer disk, these planets grew rapidly and reached enormous sizes.

The Role of Jupiter in “Clearing the Neighborhood”

Jupiter, our largest planet, exerted strong gravitational influences, shaping orbits and throwing smaller objects into new trajectories. This interplay contributed to the formation of the asteroid belt—a region where leftover rocky chunks circle the Sun between Mars and Jupiter. It’s likely that Jupiter’s presence prevented another Earth-sized planet from forming there, further underscoring how dynamic gravitational interactions can define which and how many worlds exist.

Diagram: Planetary Layout from the Sun Outward

Diagram: From the scorching inner solar system to the icy outer reaches

Leftover Worlds, Dwarf Planets, and More

We officially recognize eight planets, but our solar system contains many other interesting objects. Pluto, once called the ninth planet, was reclassified as a dwarf planet. Alongside Pluto, there are other dwarf planets like Ceres in the asteroid belt and Eris in the outer solar system.

Many researchers suspect there could be hundreds of such dwarf worlds in the distant Kuiper Belt and possibly the Oort Cloud. These aren’t typically counted among the “main planets,” but they highlight that the process of planet formation can generate a wide range of celestial bodies, some big enough to be called dwarf planets, others too small to qualify.

Why Didn’t Everything Merge Into One Planet?

Planetesimals grew where local gravity favored coalescence, but they also orbited a massive star (the Sun). Different neighborhoods in the protoplanetary disk could form multiple “growth hubs,” each eventually becoming a full-fledged planet.

The disk itself wasn’t perfectly uniform—subtle variations in density and composition gave different regions unique opportunities for building planetary cores. Hence, multiple accumulation points developed, each swirling into distinct orbits.

Cosmic Collisions and Planetary Diversification

The early solar system was bombardment central—think of a demolition derby in space. Collisions between embryonic planets (called protoplanets) could sometimes merge them into bigger worlds, or in other cases, shatter them into debris that later coalesced into smaller bodies.

For example, scientists suspect Earth’s Moon formed when a Mars-sized object crashed into our planet, ejecting a ring of material that ultimately shaped the Moon. Similarly, Uranus’s sideways tilt may be the result of a giant impact that knocked its axis off-kilter.

Collisions didn’t just create orbits and spin orientations; they also scattered smaller planetesimals across the solar system. Some ended up in the Kuiper Belt, others in the Oort Cloud, and many were pulled into the Sun or ejected into interstellar space.

Exoplanets: A Wider Lens on Why Our Solar System Has Many Planets

Observing exoplanets (worlds orbiting other stars) helps us see that multi-planet systems are common across the galaxy. Some stars have even more than eight planets.

Our solar system sits somewhere in the middle of the exoplanet zoo—some exosystems form “hot Jupiters” (gas giants hugging their star), others boast super-Earths that might not exist here. The diversity found among exoplanets drives home the idea that if you have enough gas and dust circling a star, multiple planets are often the natural outcome.

Are We Typical or Special?

In many exoplanet systems, big planets migrate inward over time. Our Jupiter may have partially migrated, but not so drastically that it consumed or flung away all the rocky matter near the Sun (the Grand Tack hypothesis). This somewhat stable positioning gave our system room for multiple planets—both rocky and giant—to thrive.

Overall, we seem unique in details but not in the broad capability of forming numerous worlds. We have a good number of planets, but not so many that they destabilize each other’s orbits, allowing our solar system to remain stable for billions of years.

The Protoplanetary Disk’s Legacy

Every piece of cosmic real estate in our solar system—from the scorching surface of Mercury to the icy outskirts beyond Neptune—shares roots in the same swirling disk of dust and gas. That disk’s size, mass distribution, chemical composition, and dynamics enabled the birth of multiple planetary bodies.

Had that primordial disk been smaller or had it dissipated quicker, we might only have had a handful of planets. Conversely, a more massive disk could have formed even bigger or more numerous planets—though extreme gravitational tussles might then destabilize the system, potentially flinging planets out into interstellar space.

Under the Hood: Orbital Resonances and Gravitational Locks

Much of the solar system’s structure is influenced by orbital resonances, which occur when planets or smaller bodies orbit in integer ratios (for example, a 2:1 resonance if one planet completes two orbits for every one orbit of another). Jupiter’s moons, for instance, show classic examples of resonance, helping them stay locked in stable orbits.

In the broader solar system, such resonances can shepherd asteroids into specific paths, maintain the edges of planetary rings, and keep multiple planets from colliding. Thanks to these delicate gravitational “dance routines,” our system can maintain multiple stable orbits over eons.

A Domino Effect in Space

Early in the solar system’s development, one object’s slight orbital change could trigger shifts in another’s path, leading to a chain reaction. This cascade of influences eventually settled into a relatively balanced arrangement we see today. If we had fewer initial planetesimals, or if one giant planet had migrated aggressively, we might be telling a different story about a system with fewer, or more scattered, worlds.

Does Having Many Planets Impact Life?

Earth is our only known haven for life, but could the number of planets in our solar system have played a role in our planet’s habitability? Some scientists propose that Jupiter acted as a cosmic shield, intercepting or deflecting dangerous comets. Alternatively, Jupiter’s presence might have also hurled some comets inward, delivering water and organic compounds to Earth.

In either scenario, it appears the configuration of multiple planets helped shape the environment on Earth. We can’t say definitively that life requires many planets, but our own evolution is intertwined with these complex gravitational relationships.

Myth-Busting Planetary Formation

Myth: The Sun Simply “Spit Out” Planets

A long-discarded idea suggested planets might have been flung off the Sun like sparks. Modern astronomy, however, shows that stars can’t just “spit out” lumps of matter. Reality: The nebular hypothesis, with a swirling protoplanetary disk, is currently the best-supported explanation for how multi-planet systems arise.

Myth: Our Solar System Has Nine Planets, Including Pluto

Reality: In 2006, Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet by the International Astronomical Union. The solar system thus retains eight official planets, with many other dwarf planets recognized in the Kuiper Belt and beyond.

Myth: Planetary Formation Is Always Neat and Orderly

Reality: Early solar systems are chaotic and violent. Planetesimals and protoplanets collide, combine, or get ejected. Our final arrangement looks orderly, but it’s the result of billions of years of chaotic cleaning up.

The Many Surprises in Our Outer Frontiers

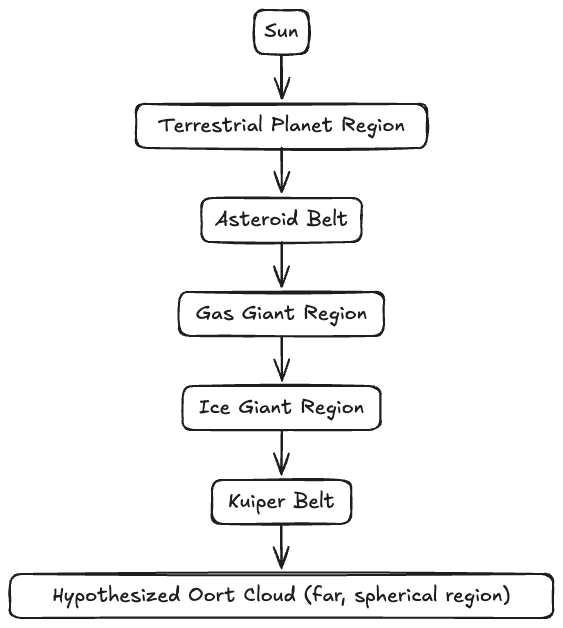

We often think of “the solar system” as just the main planets. But the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud expand our realm significantly. The Kuiper Belt is a disk-like zone of icy bodies beyond Neptune’s orbit—Pluto is a prime resident. The Oort Cloud may form a vast, spherical shell of cometary material enveloping everything.

These outer regions are remnants of that protoplanetary disk that never coalesced into full-fledged planets. They remind us that “so many planets” is a bit of an understatement, given how much else orbits our Sun in smaller orbits or scattered populations.

Diagram: Zones of the Solar System

Diagram: Inner to outer solar system, with multiple populations of objects

Common Questions About Why We Have So Many Planets

Why don’t all stars have multiple planets?

While most stars we’ve observed harbor exoplanets, not all have many. Some stars lose their protoplanetary disks quickly, or gravitationally disruptive events strip away planetary material. A star’s mass, metallicity, and environmental factors influence how many planets can form.

If Earth is rocky, why are the outer planets mostly gas?

It’s all about the frost line, the region in the disk beyond which ices can remain stable. This critical boundary allowed outer planet cores to grow larger and capture thick layers of hydrogen and helium, forming the gas and ice giants.

Could there be a hidden “Planet Nine”?

Some astronomers suspect a massive object in the far outer solar system. If it exists, it might be a Neptune-sized planet or something smaller. We’re still searching.

How many dwarf planets are out there?

Possibly hundreds. Pluto, Ceres, Haumea, Makemake, and Eris are confirmed dwarf planets, but many more in the Kuiper Belt and beyond may qualify.

Do all multi-planet systems look like ours?

Not at all. Exoplanet surveys reveal systems with super-Earths, hot Jupiters, or multiple Neptune-sized worlds orbiting in tight formation. Ours is just one variation among many.

Debris Disks, Asteroids, and the Scars of Formation

The solar system also tells its story through asteroids, meteoroids, and comets—remnants that never formed into planets. The distribution of these tiny worlds, from near-Earth asteroids to distant comets, speaks volumes about early gravitational scuffles.

Some debris got locked in orbital resonances with Jupiter (the Trojan asteroids), while other fragments ended up in highly eccentric orbits, crossing paths with Earth occasionally as meteors. The presence of such debris underscores that building multiple planets is a messy process, leaving behind cosmic crumbs.

Why Eight Planets and Not Ten or Twelve?

In the grand cosmic sense, there’s no universal rule that a star must have exactly eight major planets. Our solar system’s final lineup was shaped by:

- Solar mass and disk size

- Migration of giant planets

- Resonances and collisions

- Stabilizing or destabilizing encounters

If conditions had been slightly different, we might have ended with fewer or more major planets. The fact that eight wound up in stable orbits for billions of years is a testament to the delicate balance of cosmic processes.

The Grand Tack Hypothesis: A Giant Planet Dance

One explanation for the distribution of our planets is the Grand Tack hypothesis. It proposes that Jupiter initially migrated inward (toward the Sun), then reversed course (the “tack”) when it interacted gravitationally with Saturn.

This movement may have disrupted or ejected countless planetesimals in the inner disk. It also allowed a narrower zone for rocky planets to form, explaining why we only have four inner worlds instead of a larger batch. When Saturn formed and nudged Jupiter outward, it set the stage for the final architecture.

Could We Lose or Gain a Planet Over Time?

Planetary orbits are generally stable, so we don’t expect to suddenly “gain” a planet. Could we lose one? If a huge interstellar object passed by or if some gravitational event knocked a planet out of orbit, it’s theoretically possible, but extremely unlikely.

In the distant future, the Sun will evolve into a red giant, potentially engulfing the inner planets. But that scenario lies billions of years away. For now, our eight worlds keep circling as they have for eons.

Life on the Margins: Moons That Rival Planets

Some moons in our solar system are remarkable enough to be considered “worlds” in their own right—like Jupiter’s Europa (an icy moon with a subsurface ocean) or Saturn’s Titan (the only known moon with a dense atmosphere).

Their existence illustrates how “planetary” characteristics aren’t limited to objects orbiting the Sun directly. If we include these diverse moons, our solar system’s tally of “interesting worlds” grows far beyond eight.

Myth-Busting the Planet Count

Myth: Eight Planets Means “Barren” Elsewhere

Reality: Even though we say “eight planets,” we have an abundance of dwarf planets, thousands of known asteroids, billions of comets in the Oort Cloud, and over 200 known moons. Our system is anything but barren.

Myth: Having Many Planets Is Inherently Better

Reality: “Better” is a value judgment. Some star systems have fewer planets that might be more massive or more stable. Ours is well-suited for our existence, but that doesn’t necessarily apply to all forms of life or every star system out there.

Summary of Why Our Solar System Has So Many Planets

- Abundant Material: The nebula that birthed the Sun left a large, rotating protoplanetary disk of gas and dust.

- Disk Dynamics: Collisions and gravitational clumping in multiple “zones” yielded distinct planetary embryos.

- Thermal Gradients: Inner regions formed rocky planets; outer regions formed gas and ice giants.

- Giant Planet Influences: Jupiter and Saturn played major roles in shaping orbital resonances and clearing paths.

- Stability Over Time: The system eventually settled into long-lasting orbits, with eight major planets “surviving” the early chaos.

- Commonality Across the Cosmos: Exoplanet studies show multi-planet systems are relatively normal—our solar system’s planet count reflects typical outcomes of star formation.

FAQ Section

Why do scientists say we have eight planets instead of nine?

Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet due to new criteria set by the International Astronomical Union, which require a planet to clear its orbital neighborhood. Pluto shares its region with many Kuiper Belt objects, so it’s no longer considered a main planet.

Where do dwarf planets fit in?

Dwarf planets like Pluto and Ceres formed under similar processes but didn’t clear their neighborhoods. They still reflect the same basic mechanism of accretion in the protoplanetary disk.

Could we have missed a planet?

Astronomers have mathematical hints pointing to a possible Planet Nine beyond Neptune, but no direct observation yet. If it exists, it would likely be massive and orbit extremely far out.

How does gravity keep multiple planets stable?

Each planet follows a path balanced by the Sun’s gravitational pull and its orbital velocity. Orbital resonances and distance keep planets from smashing into each other.

Do more planets mean more chances for life?

Not necessarily. Life depends on habitability factors—temperature, water, a stable environment—rather than just planet count. However, giant planets can influence the frequency of impacts and the distribution of water-bearing comets, indirectly affecting habitability.

Final Thoughts on Planet Formation

Multiple planets aren’t a cosmic accident. They emerge from natural processes in the protoplanetary disk, shaped by collisions, orbital dynamics, and star-driven chemistry. Our solar system’s eight main planets—plus countless smaller objects—show how varied outcomes can be when nature sculpts cosmic matter around a new star.

In the bigger picture, having many planets may be more the rule than the exception, given the diversity of exoplanetary systems. It’s a testament to the universe’s prolific creativity that so many worlds can form from the same swirl of gas and dust.

Read More

- The Planet Factory: Exoplanets and the Search for a Second Earth by Elizabeth Tasker (Amazon)

- Five Billion Years of Solitude: The Search for Life Among the Stars by Lee Billings (Amazon)

- The Formation of the Solar System by M.M. Woolfson (Amazon)

- NASA Exoplanet Archive

- European Space Agency – Planetary Science

These resources delve deeper into how planets emerge, why solar systems vary, and what the latest exoplanet research tells us about our cosmic neighborhood.