TL;DR: We have 365 days in a year because Earth completes one orbit around the Sun in roughly that timeframe, refined over centuries of astronomical observations and calendar reforms.

The Ancient Roots of Our 365-Day Year

Early civilizations noticed that the Sun’s position in the sky changed gradually over time. They observed that certain star constellations reappeared each year at about the same point in the calendar, suggesting that one full cycle of solar events took around 365 days.

From the banks of the Nile to the plains of Mesopotamia, ancient stargazers recognized the annual patterns that governed planting and harvest seasons. Tracking these solar movements was far from mere curiosity; it was essential for survival. Crops needed to be sown and harvested at just the right moments, and these communities soon discovered that a near-365-day cycle aligned with seasonal markers.

Early Observations and Cultural Significance

As soon as humans connected the length of a year with celestial cues, the calendar became a powerful tool. In Ancient Egypt, the Nile’s flooding—crucial for agriculture—became synchronized to a 365-day system. Meanwhile, Mesopotamian priests observed how solar and lunar cycles influenced religious festivals. In both societies, the year was more than a cycle; it was linked to spiritual events, weather predictions, and daily life.

The challenge, however, lay in matching these calendars to the true solar year. Early estimations were slightly off. Over many decades, these errors would accumulate, causing the seasons to drift away from their usual months. As we’ll see, this drift would become a recurrent problem, prompting repeated corrections and reforms.

Earth’s Journey Around the Sun

A year, in the astronomical sense, is the time it takes for our planet to make one complete revolution around the Sun. This path is not perfectly circular; Earth follows an elliptical orbit, meaning the distance from the Sun varies slightly throughout the year. Despite this slight ellipse, our orbital period remains remarkably consistent, hovering around 365.25 days.

Orbital Dynamics and the Concept of a Tropical Year

When we discuss Earth’s annual cycle in everyday terms, we usually mean a tropical year, which is the time between two vernal (spring) equinoxes. This alignment is crucial for maintaining consistency with our seasons. After all, we want each year’s March equinox to happen around the same date on our calendar, ensuring that spring in the Northern Hemisphere (and autumn in the Southern Hemisphere) stays aligned with our notion of months.

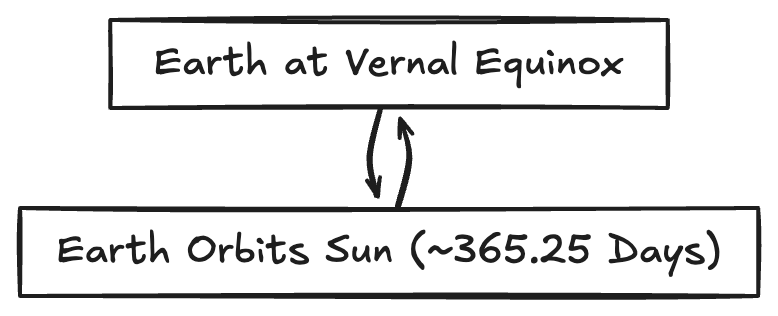

Diagram: Earth’s Year in Perspective

In this simplified diagram, Earth completes one loop around the Sun in ~365.25 days. The path is elliptical, but we illustrate it simply here, focusing on the core idea of one full orbit. Each equinox occurs as Earth’s tilt and position align, dictating the transition from one season to the next.

Rotation vs. Revolution

It’s easy to confuse Earth’s rotation (the time it takes to spin once on its axis, about 24 hours) with its revolution (the time it takes to go around the Sun). Rotation defines our day, while revolution defines our year. If Earth’s rotation period were different, we’d still have about the same length of year, just with more or fewer days.

The Role of Earth’s Tilt and Seasons

A major factor in the seasons is Earth’s axial tilt, about 23.5° relative to the plane of its orbit. This tilt causes one hemisphere to receive more direct sunlight at certain points in Earth’s orbit, creating summer in that hemisphere, and less direct sunlight, creating winter in the other. Over the course of one revolution, each hemisphere experiences a full cycle of seasonal changes, making the ~365-day year an intuitive framework.

Equinoxes and Solstices as Seasonal Markers

- Equinoxes: When the Sun’s rays shine directly over Earth’s equator. Day and night are nearly the same length.

- Solstices: When the Sun’s rays reach the farthest point north or south. One hemisphere experiences summer solstice, while the other experiences winter solstice.

The regularity of these equinoxes and solstices has guided us to define a year that lines up with seasonal rhythms. If it took significantly less or more time for Earth to orbit the Sun, our entire calendar would shift—and so would our daily routines.

Charting the Calendar: How 365 Became Official

Although the solar year is about 365.25 days, ancient societies tried to fit this into neat cycles. Early calendars blended lunar months with solar observations, but matching these two cycles was notoriously difficult. The Moon’s orbit around Earth takes roughly 29.5 days, leading to about 354 days in a twelve-month lunar calendar, creating a mismatch with the solar year.

The Julian Calendar Reform

By the 1st century BCE, the Roman calendar was out of alignment with the seasons by several months. Julius Caesar introduced the Julian calendar, which aimed to fix this drift. It established a year of 365 days with an extra day, called leap day, every four years. The average year length was thus 365.25 days, which was very close to the real solar year.

Yet, the Julian calendar still had a slight discrepancy. The true solar year is approximately 365.2422 days—meaning the Julian system was off by about 11 minutes per year. Over centuries, this gradual drift accumulated.

The Gregorian Adjustment

By the 16th century, the Julian calendar had drifted about 10 days from the actual equinox. Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar in 1582, which added a refined rule to the leap year concept:

- Every year divisible by 4 is a leap year.

- Except years divisible by 100, which are not leap years.

- Except those divisible by 400, which remain leap years.

This approach yields an average year of 365.2425 days, matching the tropical year even more closely. Today, most of the world uses this Gregorian system, which explains how we get 365 days in a common year and 366 days in a leap year, ensuring minimal seasonal drift.

Peeling Back the Layers of Accuracy

Even with the Gregorian reforms, the calendar is an approximation of the tropical year. Over extremely long periods, Earth’s orbit and tilt can shift. But for all practical purposes, 365 days (and an extra day added periodically) holds our seasons steady and keeps our daily lives in sync with the natural world.

Precession and Other Astronomical Nuances

Earth’s axis itself wobbles over millennia in a movement called precession. Imagine a spinning top that slowly traces a circle with its tip. This wobble takes about 26,000 years, gradually altering the alignment of Earth’s poles and the equinoxes. These changes happen on timescales far beyond a single lifetime, yet they confirm that our timekeeping systems must remain flexible to maintain accuracy over millennia.

The Influence of Culture and Observation

Cultural beliefs have shaped calendars just as much as astronomy. In many ancient societies, religious festivities or dynastic celebrations influenced how days were counted. Solar eclipses, harvest times, or the rising of certain bright stars (like Sirius in Ancient Egypt) were key signals for marking the new year.

Even today, our sense of what a year “should be” is deeply rooted in tradition. While scientists refine astronomical measurements, the average person expects winter to fall in December and summer to fall in July (in the Northern Hemisphere)—an expectation shaped by centuries of cultural usage.

When Earth Was a Basketball: Scale and Distance

To visualize Earth’s year more concretely, imagine Earth as a basketball (about 24 cm in diameter). In this comparison:

- The Sun would be roughly 25 meters (80 feet) away.

- Earth would revolve around the Sun at speeds that seem unimaginable for a basketball, but it would still complete its “lap” in about 365 “days.”

In this analogy, you see how small Earth appears next to the vastness of space. The “path” it takes around our Sun is enormous, yet it remains consistent enough that the time it takes to complete one orbit stays roughly stable year after year.

Why 365, Not 360 or 400?

Many might wonder: Why didn’t ancient astronomers or modern scientists opt for a rounder number like 360 or 400 days? A 360-day year would simplify many calculations, but it wouldn’t align well with Earth’s actual solar cycle. After just a few years, the seasons would shift so dramatically that calendars would lose all semblance of consistency.

A 400-day year, likewise, is too large. We’d constantly misalign with the real seasons, and eventually, it would be a winter’s day in August and a summer afternoon in February. Over millennia, small inaccuracies accumulate, but large mismatches make a calendar useless.

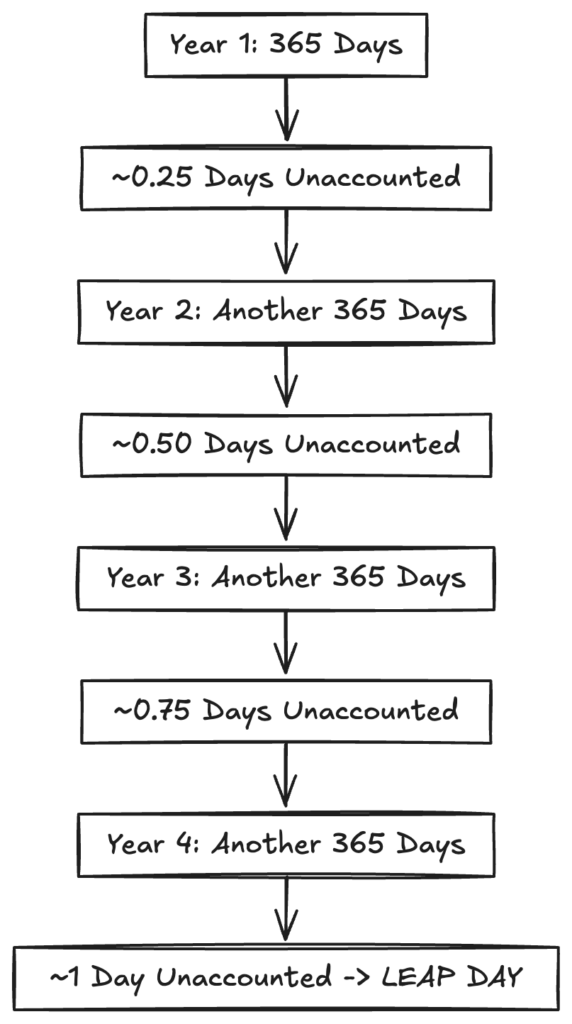

The Leap Year Mechanism: Why We Need It

To handle that extra quarter day (0.2422 to be more precise), we introduce leap years. The year 365 is slightly shorter than the solar year, so we add a day to the calendar every four years. However, because the real fraction is slightly less than 0.25, we skip leap days in most century years. Yet we keep them if the century is divisible by 400.

This system ensures that over the course of 4 centuries—146,097 days total—we maintain near-perfect alignment between the calendar year and the tropical year.

Myth-Busting the Idea of a Perfect Calendar

Myth: There is a single perfect way to measure a year that never changes.

Reality: Although the tropical year is about 365.2422 days, even that number can shift due to variations in Earth’s orbit, gravitational interactions with the Moon, and the gradual slowdown of Earth’s rotation. The Gregorian calendar does a fantastic job overall, but “perfect” is relative to how you measure time.

Myth: All cultures see the year exactly the same.

Reality: Many communities still use lunar calendars, or combinations of lunar and solar cycles (lunisolar calendars). The Islamic Hijri calendar is purely lunar, with 12 months of 29 or 30 days, totaling about 354 or 355 days per year. Meanwhile, the Jewish calendar is lunisolar, occasionally inserting a leap month to keep festivals in line with the seasons.

Comparing Earth’s Year to Other Planets

A year on another planet is the time it takes that planet to orbit the Sun once. For instance:

- Mercury: About 88 Earth days

- Venus: About 225 Earth days

- Mars: About 687 Earth days

- Jupiter: About 12 Earth years

- Saturn: About 29 Earth years

Thus, “365 days” is purely Earth-centric. If you traveled to Mars, you’d wait an additional 322 Earth days to declare “one Martian year.”

Calendar Innovations and Alternative Proposals

While the Gregorian calendar is widely adopted, various proposals aim to simplify or reorganize the months and weeks. Some propose a 13-month calendar with each month containing 28 days, plus 1 or 2 extra days that don’t belong to any week. These suggestions, however, have rarely caught on, because habit, tradition, and global unity keep the Gregorian system firmly in place.

The International Fixed Calendar Concept

This concept sets each month to exactly 28 days, creating 13 months for a total of 364 days, plus one or two leftover days (often labeled “Year Day”). Despite simplifying date calculations, it struggles to gain traction due to the massive socio-cultural upheaval it would require.

Beyond the Gregorian Year

In scientific fields, especially astronomy, specialized time standards are used. For instance, Julian Dates count days continuously from January 1, 4713 BCE, simplifying calculations for observational data. Another concept is the sidereal year, measuring Earth’s orbit relative to distant stars rather than the Sun. Each approach serves a unique purpose, highlighting that a “year” can mean different things depending on the context.

Small Shifts, Big Impacts

Even minor deviations in Earth’s orbital period can have intriguing consequences. Over the centuries, entire ecosystems have adapted to the 365-day timeframe, from migrating birds to seasonal plant cycles. A consistent year fosters predictable seasonal shifts, supporting the global tapestry of life.

Common Misconceptions About 365 Days

Myth: The Sun Orbits the Earth

This ancient misconception arises from our daily experience of seeing the Sun move across the sky. We know from centuries of scientific research that Earth orbits the Sun, not the other way around, and the ~365 days is the duration of that orbit.

Myth: Earth’s Orbit Is a Perfect Circle

While our orbit is nearly circular, it’s actually elliptical. We’re slightly closer to the Sun during perihelion (around early January) and a bit farther away during aphelion (around early July). This elliptical shape doesn’t change the length of the year drastically; it simply shifts the intensity of seasons a bit.

Myth: Daylight Hours Are Always the Same Each Year

Seasonal patterns do repeat, but micro-changes—like leap years, atmospheric conditions, or slight shifts in Earth’s tilt—can cause subtle variations in daylight hours. However, these changes are so small that most people never notice them.

The Human Connection to the Year

We often measure our lives in years, marking birthdays and anniversaries. So 365 days (or 366, if leap year) becomes deeply personal. Because the Earth-Sun relationship underlies so many daily and seasonal events, each orbit is laced with sentiment and memory.

Celebrations and Festivals

Human festivals usually revolve around these natural cycles:

- Harvest festivals timed to autumn in many cultures.

- Spring festivals like Nowruz, heralding the rebirth of nature.

- Winter traditions such as Christmas or Hanukkah, which coincide with or near the winter solstice in the Northern Hemisphere.

These seasonal celebrations are interconnected with the notion of a 365-day year, reinforcing cultural rhythms across continents.

Seasonal Drift and Long-Term Calendrical Adjustments

The slight mismatch in day count means that we rely on periodic corrections to stay synchronized with the astronomical year. Over decades, if we didn’t add leap days, our calendar would drift, and winter would slowly march toward summer months.

Diagram: Calendar Drift Without Leap Years

Without these corrections, a calendar can drift by about one day every four years, a noticeable offset over decades and centuries.

How Timekeeping Shapes Societies

The concept of a 365-day year influences everything from school schedules to fiscal years. In many cultures, children enter new “grades” at roughly the same time each year. Organizations issue annual reports and budgets, aligning with 12-month cycles. Even major sports seasons revolve around these intervals, shaping entire economies and social calendars.

Innovations in Timekeeping

Technological advancements like atomic clocks and GPS push our ability to measure time ever more precisely. While we still use 365 days as our practical yardstick, the scientific community can measure Earth’s rotation and orbital period with mind-boggling accuracy, refining these numbers as needed.

The Psychology of a Year

Human beings naturally seek patterns and cycles. We anchor our goals—like New Year’s resolutions—to these repeated intervals. We also measure personal growth and reflect on achievements at year’s end. The number 365 becomes woven into our collective psyche, an anchor that unifies global cultures, whether or not people consciously think about Earth’s orbit.

The Importance of Day Count Consistency

If the length of a year changed dramatically, it would disrupt everything from farming cycles to crucial climate models. Scientists rely on stable data to predict phenomena like El Niño or monsoon seasons. A consistent year length ensures predictable solar radiation patterns, vital for life on Earth.

The Subtle Adjustments in Our Calendar’s Future

Given the slow changes in Earth’s rotation and orbit, extremely long-term forecasts suggest that future civilizations might need to introduce new calendar tweaks. For instance, a day might be added or removed over thousands of years if Earth’s rotation continues to slow. However, these are problems for far-future humans.

The Ongoing Quest for Accuracy

Timekeeping agencies, like the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), occasionally add “leap seconds” to keep official time in sync with Earth’s rotation. Though this affects clocks more than calendars, it underscores that our planet’s movements are not perfectly stable. Even so, we can expect 365 days (with leap year adjustments) to remain our best approach for the foreseeable future.

Bridging Science and Daily Life

One of the beauties of the 365-day year is how it merges the cosmic and the commonplace. Even if you rarely ponder orbital mechanics, your everyday routines—from summer vacations to winter holidays—reflect the journey Earth takes around the Sun. Knowledge of why we have 365 days weaves astronomy into normal life.

The Tangible Ties to Seasons

That intangible feeling of each season’s arrival is literally Earth’s tilt and orbit in action. From budding flowers in spring to the longer nights of winter, these experiences tie our sense of time to ancient cosmic rhythms.

FAQ Section

What if we used a 360-day year?

We would drift out of sync with the real solar year, quickly causing seasons to appear earlier in the calendar. In just a few decades, winter might fall in what used to be late autumn, creating confusion for agriculture, festivals, and daily life.

How did ancient people measure days without modern tools?

Ancient civilizations closely observed the Sun, Moon, and stars—sometimes using rudimentary sundials and water clocks. Over many generations, they refined their observations, aligning them with solstices, equinoxes, and noticeable star alignments.

Why are some calendars lunar, some solar, and some lunisolar?

Different cultures placed varying degrees of importance on the Moon’s phases versus solar events. Purely lunar calendars (like the Islamic Hijri calendar) pivot around the Moon, while solar calendars (like the Gregorian) focus on Earth’s orbit around the Sun. Lunisolar calendars (like the Jewish calendar) blend both, adding leap months to match lunar months with solar seasons.

Is there a possibility that our year length might change significantly?

In the short term, no. Earth’s orbit remains quite stable. Over hundreds of millions of years, gravitational interactions, solar mass loss, and Earth’s slowing rotation could slightly alter the length of a year, but changes on that scale are extraordinarily gradual.

Why don’t we adopt a more “logical” calendar like a 13-month system?

Such proposals face enormous cultural, religious, and economic hurdles. The familiarity and global integration of the 12-month Gregorian system make it tough to replace, even if alternative calendars might offer neat divisions on paper.

Are leap seconds related to leap years?

No. Leap seconds correct for irregularities in Earth’s rotation to keep clocks aligned with solar time, whereas leap years ensure the calendar stays in sync with the tropical year.

Does the start of the year always coincide with perihelion or aphelion?

Not exactly. Earth often reaches perihelion (closest point to the Sun) in early January, but the exact date can shift. These occurrences don’t define the calendar’s start; instead, our calendar is tied to seasonal markers and historical tradition.

Why do we say a year has 365 days if it’s really about 365.2422?

It’s simpler and more practical to talk about a “365-day year.” We handle that extra fraction through the leap year rule. Over time, those leap days bring the average in line with the actual solar cycle.

Read More

- The Calendar: The 5000-Year Struggle to Align the Clock and the Heavens—and What Happened to the Missing Ten Days by David Ewing Duncan

- Empires of Time: Calendars, Clocks, and Cultures by Anthony F. Aveni

- The Oxford Companion to the Year by Bonnie Blackburn and Leofranc Holford-Strevens

These references offer deeper insights into how humanity has grappled with the mysteries of calendars and time. Through them, you’ll discover more about the remarkable journey that has shaped our 365-day year into the reliable system we live by every day.