TL;DR: Yes, people can develop human echolocation skills using mouth-clicks and specialized listening techniques, though it requires training and practice to interpret returning echoes for spatial awareness.

Understanding the Concept of Echolocation

Echolocation sounds like something out of a superhero movie. Bats, dolphins, and a handful of other animals use it naturally. They emit sounds—like clicks or pulses—and listen to the echoes bouncing off objects in their environment. Those echoes create a kind of “acoustic picture” that helps these animals navigate and hunt in complete darkness.

Humans don’t have biological sonar equipment built-in, but we do have flexible brains and excellent hearing capabilities. With training, we can learn a form of human echolocation. By making clicking sounds with our tongues or snapping our fingers, we can interpret the returning echoes to get an idea of where walls, doors, or other obstacles might be. Remarkably, some visually impaired people have developed this skill to a high degree, navigating complex surroundings with minimal assistance.

How Animals Use Echolocation as a Model for Humans

Bats and Dolphins as Champions

When thinking about echolocation, most people picture bats flitting around at night or dolphins gliding through murky ocean waters. Bats emit high-pitched squeaks that are well above human hearing ranges, while dolphins produce clicks and whistles. The principle remains the same: these creatures analyze returning echoes to construct a mental map of their environment.

Bats, for example, can detect the position of a tiny mosquito. Dolphins can locate fish even in dark or cloudy waters. This sense is so refined that they can differentiate the shape, size, and texture of objects from distances that seem incredible to us.

What Humans Can Learn

We might not have specialized nose leaves like some bats or the advanced melon organ of dolphins, but we share a crucial trait: a flexible auditory cortex. Our brains can adapt to interpret auditory cues with practice. Given that we have distinct mouth structures capable of producing clicks, we can repurpose that ability into a rudimentary form of echolocation. While we can’t duplicate the ultrasound frequencies of a bat or the subaquatic range of a dolphin, we can still harness echoes in ways that enhance our spatial awareness.

The Science of Human Echolocation

Brain Plasticity and Sensory Substitution

Human echolocation relies on brain plasticity, which is the ability of our nervous system to adapt. When a person loses vision or trains intentionally, the brain “re-maps” resources to better process auditory and tactile information. Over time, areas of the brain typically responsible for vision may help decode audio signals, including echoes.

In functional MRI studies, blind echolocators sometimes show activity in the visual cortex when performing echolocation tasks. This phenomenon suggests a type of sensory substitution—hearing takes on responsibilities once managed by sight. The brain is flexible enough to repurpose its “visual centers” for audio-based spatial tasks.

How Echoes Provide Spatial Cues

An echo is simply sound bouncing back. But if you listen closely, echoes reveal:

- Distance to an object, inferred from how long the echo takes to return.

- Direction, based on which ear receives the sound first or with greater intensity.

- Size and shape, by how the echo’s frequency and duration change upon reflection.

For humans, mouth clicks produce a short, sharp sound. The returning echo might be extremely faint, but through consistent practice, people learn to detect subtle changes in pitch and volume. This helps them form a mental picture of a room’s layout or the presence of nearby obstacles.

Evidence That Humans Can Echolocate

Notable Individuals

Several blind individuals have gained fame for advanced echolocation. For instance, Daniel Kish, sometimes called “Batman,” has taught himself to produce tongue clicks and interpret echoes well enough to hike, cycle, and navigate unfamiliar environments. Another example is Juan Ruiz, who can perform tasks like riding a bicycle through open areas using echolocation cues.

These cases prove that echolocation isn’t just a theoretical concept. Real people have harnessed it in practical, everyday settings. They provide living examples that humans can train their ears and brains to gain a new sense—echo-based navigation.

Scientific Experiments

Researchers have set up controlled experiments, placing blindfolded participants in rooms with obstacles. Some participants were already trained in echolocation, while others were novices. In many studies, those who had practiced mouth-click echolocation could locate walls and objects with surprising accuracy. Novice participants, given even a few hours of training, started to pick up rudimentary skills.

Brain imaging supports these findings. When trained echolocators listen to echoes, their brain scans show enhanced activity in both the auditory cortex and, surprisingly, portions of the visual cortex. This underscores how thoroughly the brain can adapt to interpret echoes as a form of “vision” through sound.

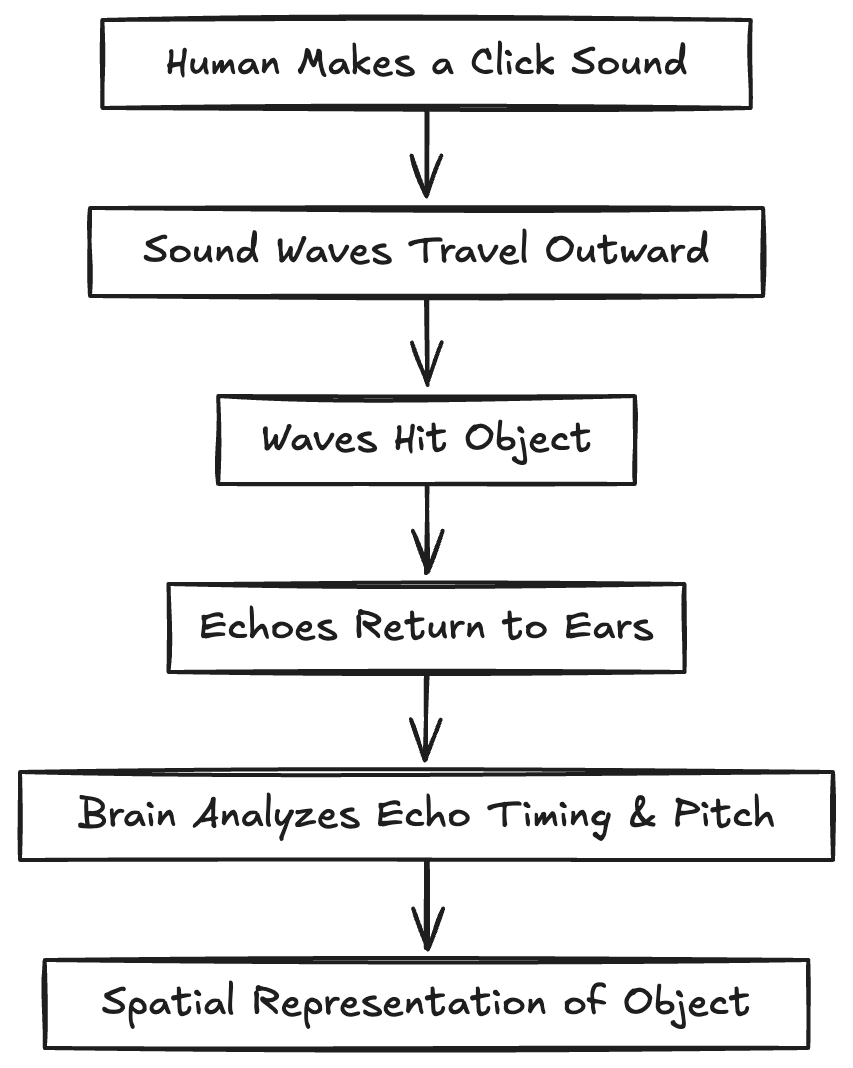

Diagram: The Basic Cycle of Human Echolocation

Diagram: How Mouth-Click Echolocation Works

Diagram Explanation: You produce a click (A), the sound waves move through the environment (B), strike an obstacle (C), then bounce back as echoes (D). Finally, your brain processes these echoes (E) to form a rough mental image (F).

Training to Learn Echolocation

Getting Started with Mouth Clicks

For beginners, the simplest way to start is to develop a consistent mouth click. The recommended technique is to place your tongue against the roof of your mouth, then quickly pull it down, creating a sharp “tssk” or “tick” sound. It should be short and high-pitched, ensuring a clear echo.

It may feel awkward at first, but consistent clicks are crucial. Variation in pitch or volume can complicate echo interpretation. A stable, repeatable “anchor” sound helps the brain learn the differences in echo characteristics.

Early Exercises

New learners often begin in a quiet indoor environment with a large flat wall. You might stand a few meters away, click, and listen for the echo’s return. Then, move closer or farther from the wall and note how the echo changes. By repeating these exercises, the brain starts to link echo timing and intensity to real distances.

Over time, you can graduate to multiple objects or corners, focusing on whether the echo arrives from the left, right, or front. Some people even practice with basic obstacles like open doors or chairs, learning how different shapes produce distinct echo signatures.

Advanced Techniques

Once you master the basics, you can try more complex challenges:

- Navigating hallways or corridors using clicks.

- Identifying materials like wood vs. metal by subtle differences in echo texture.

- Detecting overhead obstacles, like low-hanging tree branches.

Some advanced echolocators can even perform tasks in crowded spaces or ride bicycles along quiet streets, demonstrating a remarkable level of environmental awareness through sound.

Neural Plasticity: Why Echolocation Is Feasible

The Adaptable Brain

The concept of neural plasticity underpins all learning, from playing the piano to speaking a new language. Echolocation training taps into the auditory system, but it also recruits spatial reasoning skills usually handled by vision. Over months of practice, the relevant neural pathways strengthen. Some echolocators note that once they start, their brain keeps refining the skill as it interprets more echoes in daily life.

Time and Commitment

Learning to echolocate effectively is not an overnight process. For some, it can take months or years of patient training to reach advanced proficiency. The average person can pick up a rudimentary sense of distance to large obstacles in weeks if they practice daily in a structured manner. The key is consistency—regular click practice in real-world settings.

The Role of Hearing and Environment

Hearing Sensitivity

People with typical hearing can often learn echolocation, but those with heightened auditory sensitivity may progress faster. Some who are blind from birth develop an almost uncanny ability to detect extremely faint echoes. However, being blind is not a prerequisite—sighted people can learn the skill too, although they may rely more on sight in daily life, slowing their reliance on echolocation.

Environmental Noise

Echolocation works best in quiet or moderately noisy areas. Loud environments can drown out the subtle echoes you need. Realistically, few modern spaces are silent, so part of the skill is filtering other sounds while focusing on the click echoes. Some advanced practitioners can echolocate even in busy city streets, but that requires refined listening and experience.

Applications and Real-World Benefits

Mobility for the Visually Impaired

The most obvious benefit is for people with vision loss. Echolocation can serve as a powerful navigation aid, supplementing canes or guide dogs. It fosters greater independence and confidence, allowing them to identify doorways, steps, or approaching obstacles.

Enhanced Spatial Awareness for Everyone

Even sighted individuals can harness echolocation to refine their sensory awareness. Rock climbers, for example, might use it to gauge the depth of cracks in a cave. Certain law enforcement or search-and-rescue teams have experimented with echolocation-like techniques to detect objects in near-darkness.

Boost to Cognitive Skills

Echolocation training fosters a heightened sense of focus and auditory discrimination. Engaging these deep listening skills may also exercise the brain, potentially improving concentration and mental sharpness. While research is still ongoing, anecdotal reports suggest broader cognitive benefits.

Myth-Busting: Common Misconceptions

Myth: Human Echolocation Is as Powerful as a Bat’s

Reality: Humans can develop impressive echolocation, but we aren’t natural experts. Bats use ultrasound frequencies with specialized ears and vocal structures. Our human system is more limited in range and detail, but still quite functional for basic navigation and object detection.

Myth: Only Blind People Can Learn It

Reality: Sighted people can train in echolocation too. Though blind individuals might rely on it more heavily, the skill is accessible to anyone who puts in the time and practice. The main difference is that sighted individuals often don’t need it for everyday tasks, so they may not develop it to an advanced level unless they choose to do so.

Myth: It’s Instant or Requires No Practice

Reality: Echolocation is a learned skill, requiring consistent training. Just like learning a musical instrument, you get better with repeated, focused practice over many weeks or months. There is no magic switch that grants instant sonar vision.

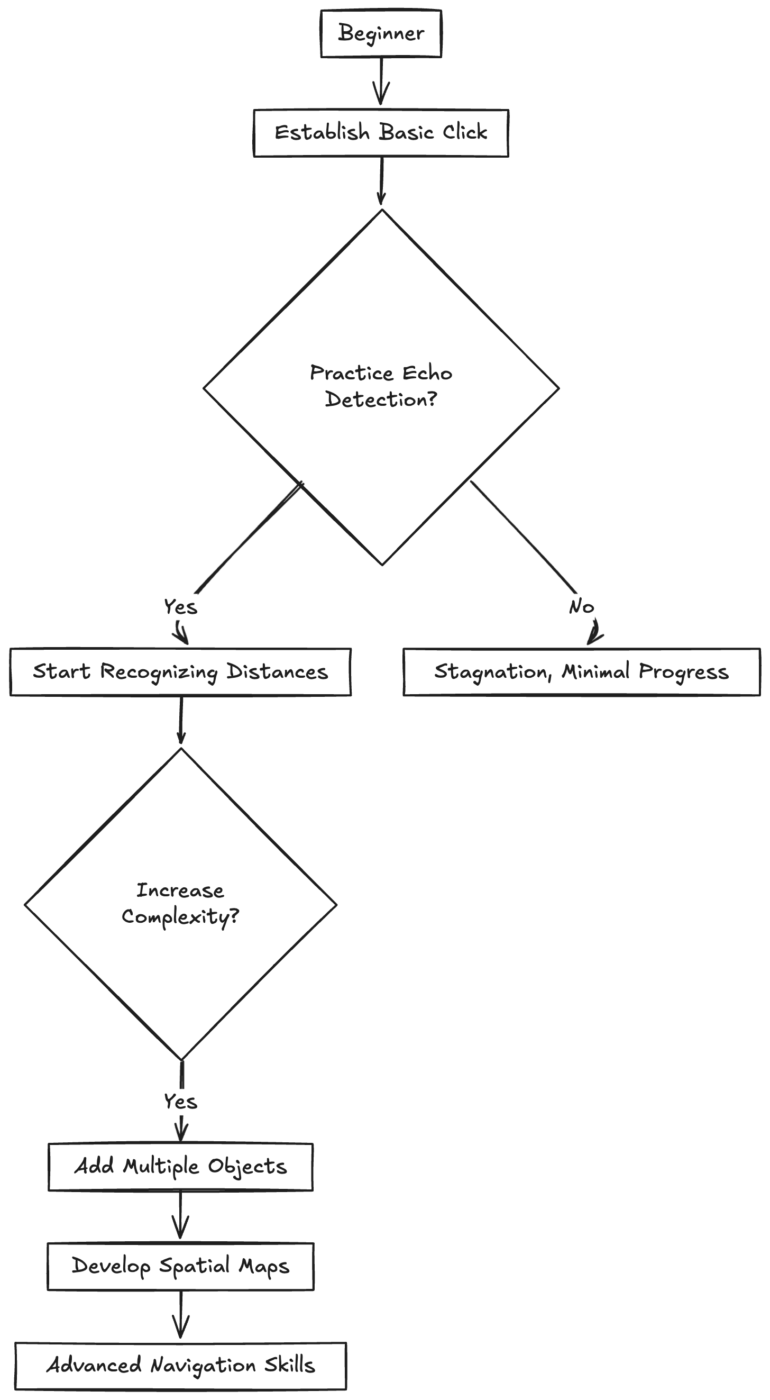

Diagram: Pathways to Learning Human Echolocation

Diagram: From Beginner to Advanced Echolocator

Diagram Explanation: This flow shows the gradual path from a beginner (A) who establishes a basic mouth-click (B), to someone who consistently practices (C) and moves on to advanced navigation skills (H). A lack of practice (I) halts progress.

Potential Drawbacks and Challenges

Physical Strain on Voice

Repeated tongue-clicking or vocal clicks can initially strain the mouth and throat if done excessively. Beginners sometimes report jaw fatigue. However, this usually diminishes as they develop a relaxed, efficient clicking technique.

Social Perceptions

Some might feel self-conscious making clicking sounds in public, especially at the beginning. Cultural norms or awkward stares can deter individuals from practicing openly. Overcoming these social barriers is part of the journey, and many echolocators find they become more comfortable once they see the significant benefits.

Not a Full Replacement for Sight

While echolocation can provide valuable spatial cues, it doesn’t replicate the rich detail and color vision provides. It’s incredibly helpful for obstacle detection and broad environment mapping, but it won’t let you read text or notice subtle color differences. It’s an augmentation, not a complete stand-in for sight.

FAQ

Can a person echolocate if their hearing is not perfect?

It depends on the degree and nature of hearing loss. Mild to moderate impairments can still allow for echolocation, though progress may be slower. Individuals should consult audiologists to optimize hearing aids if they plan to pursue echolocation training.

Do echolocators have super-hearing?

Not exactly. Many echolocators simply learn to pay attention to faint echoes that most people ignore. Their hearing may be normal, but their brain’s processing of sound is more refined due to training.

Is it dangerous to rely solely on echolocation when walking around?

It’s best viewed as one tool in a toolkit. Even advanced echolocators may use a cane or keep a hand free in unfamiliar areas. Combining echolocation with caution ensures safer navigation.

Do children learn echolocation faster than adults?

Children often adapt quickly because of their high neural plasticity and fewer inhibitions about making clicks in public. Adults can still learn effectively—it might just require more conscious practice and perseverance.

Can you use echolocation in noisy environments?

Yes, but it’s more challenging. Loud background noise can mask the delicate echoes. Experienced echolocators learn to filter out irrelevant sounds, though extremely noisy settings can limit effectiveness.

Relatable Comparisons

- Like Tuning into a Radio Station: Just as you carefully adjust a dial to pick up a faint signal, learning echolocation involves tuning your brain to detect subtle echoes masked by ambient noise.

- Similar to Blindfold Chess: Chess masters who play blindfolded rely on an internal map of the board. Echolocators create a mental map of the environment using sound. Both skills require mental visualization and memory.

Practical Tips to Get Started

- Practice in a quiet room: Stand facing a wall and produce consistent clicks. Move step by step closer, focusing on changes in echo timing and loudness.

- Use a consistent click: A short, high-pitched “tssk” is often recommended. Consistency is key; random or varying clicks can complicate echo analysis.

- Introduce small objects: Place cardboard boxes or chairs in your practice space, trying to sense their location. Walk around them slowly while continuing to click.

- Keep sessions short: It’s mentally demanding at first. Ten to fifteen minutes of focused training per day can yield steady improvements.

- Record your progress: Some learners benefit from keeping a journal, noting what shapes or distances they can reliably detect.

Success Stories: Inspiration for Aspiring Echolocators

Daniel Kish: “Batman” of the Real World

Born blind, Daniel Kish taught himself tongue-click echolocation in early childhood. He eventually founded a nonprofit to teach others. Kish has navigated wilderness trails alone, even riding bicycles in safe areas. His story underscores the potential for echolocation to grant remarkable freedom to the visually impaired.

Ben Underwood: Mastering Sound to “See”

Ben Underwood lost his eyes to cancer as a young child. He learned to sense objects by making quick clicking noises with his tongue. Remarkably, he could identify parked cars and trees while walking or even skateboarding. Although he passed away from cancer as a teenager, his example shows how quickly children can adapt to new sensory techniques.

Beyond Mobility: Other Uses of Human Echolocation

Research and Technological Developments

Scientists are investigating how echolocation training might benefit not only the blind community but also search-and-rescue personnel or individuals working in dark, confined environments. There is ongoing work with specialized microphones and earphones to amplify echoes, combining human echolocation with technology.

Enhanced Self-Awareness and Concentration

Some practitioners report that learning echolocation helps them become more in tune with their surroundings. They mention feeling less anxious in unfamiliar spaces and more connected to the acoustic details of the world. This heightened awareness may even cross over to other skill sets, such as music or language learning.

Myth-Busting: “Echolocation Replaces All Vision Needs”

Myth: Once you learn echolocation, you can ditch your cane or guide dog.

Reality: Echolocation is powerful but not an all-in-one solution. Many individuals still rely on canes, guide dogs, or visual aids for fine details. Echolocation is best seen as a complementary skill—an additional layer of sensory input that offers real, tangible benefits but doesn’t substitute every aspect of vision.

The Future of Human Echolocation Research

Brain Mapping and Virtual Reality

Ongoing studies explore brain mapping techniques to see precisely how the auditory cortex and visual cortex collaborate in echolocation. Some labs use virtual reality or specialized headphones to simulate echoes in controlled environments, allowing scientists to track how learners progress over time.

Potential for Early Curriculum

Given that children’s brains are especially plastic, a growing number of educators suggest introducing echolocation games in schools for blind or visually impaired students. Preliminary success stories hint that kids can learn these skills faster and more naturally, potentially gaining a lifetime advantage in mobility and independence.

Conclusion: A Remarkably Trainable Human Skill

So, can humans learn to echolocate? Absolutely. While not as intuitive or powerful as the echolocation of bats or dolphins, humans possess the neural plasticity and auditory capabilities to detect echoes produced by simple mouth clicks. With consistent training, practitioners—both blind and sighted—can develop an impressive level of “echo vision,” allowing them to sense walls, doorways, and even smaller obstacles in their path.

This skill opens new vistas of independence, particularly for those with vision impairments. It also exemplifies the adaptability of the human brain, revealing our potential to develop extraordinary abilities once thought to be unique to other species. While it’s not a panacea for blindness or a total replacement for vision, echolocation stands as a testament to human resilience and creativity—showing that with time, effort, and perseverance, we can indeed “see” through sound.

Read more

- The Mind’s Eye by Oliver Sacks

Explores how people adapt to vision loss, highlighting the brain’s flexibility in finding new ways to perceive.