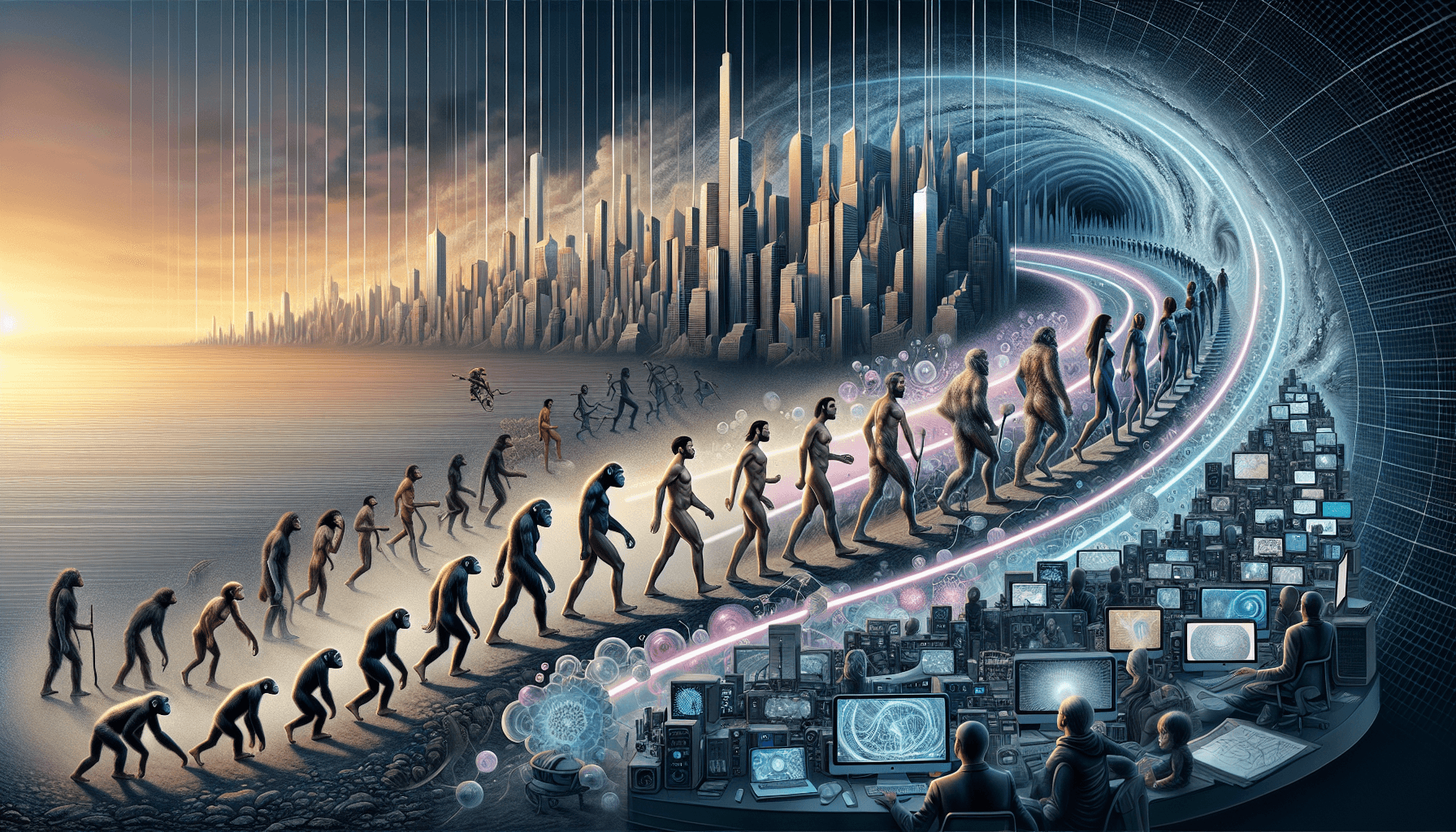

TL;DR: Humans are still evolving in subtle ways—there’s no sign we’ve hit our final form.

It’s tempting to think that because we’ve built skyscrapers, decoded the human genome, and scattered ourselves across the globe, we might have reached a biological plateau. If our everyday lives are no longer marked by life-or-death battles with nature, what’s left to shape our genetic destiny?

In reality, evolution never truly takes a break. While it might not happen on timescales we easily observe, our species continues to undergo genetic shifts. Some occur at a glacial pace, others more quickly—depending on factors like environment, culture, and technology. So the short answer is that humans haven’t hit a hard stop in our evolutionary journey.

But to really dig into whether we’ve peaked, we need to understand the basics of evolutionary forces, how modern life might be changing these forces, and whether future developments—like genetic engineering—could eventually overshadow traditional evolution. Let’s uncover what’s happening right beneath our skin, generation by generation.

Evolution 101: Key Drivers That Shape Us

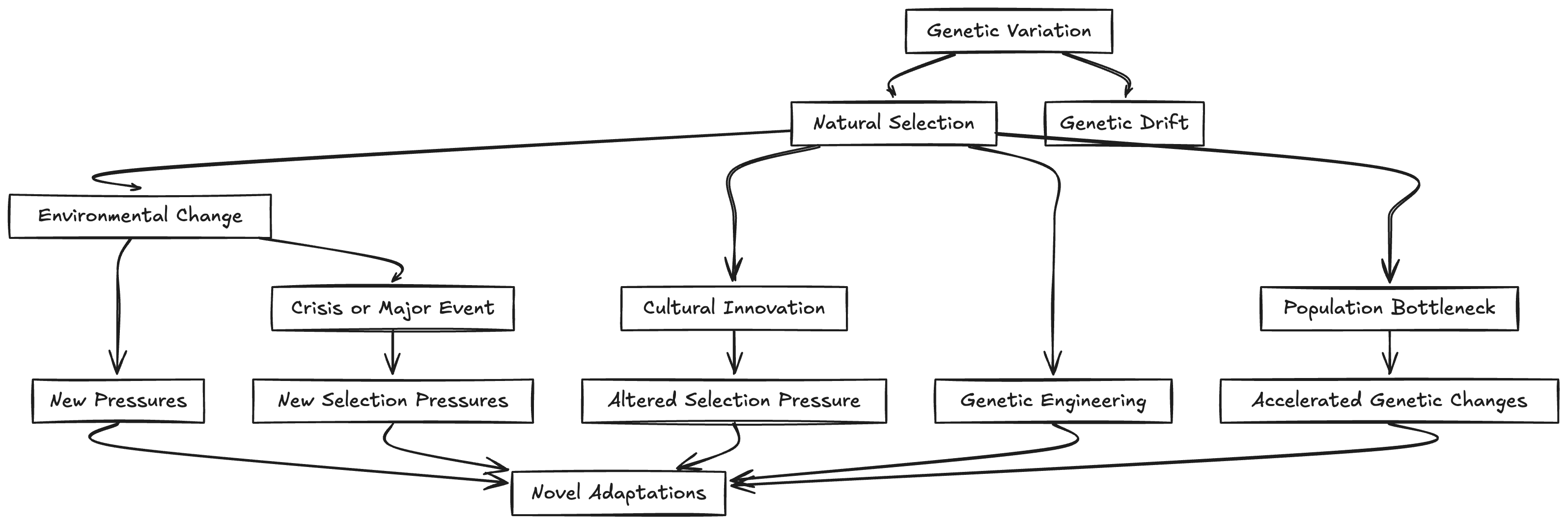

Before exploring how modern life might be altering evolution, it helps to recall how evolutionary processes work. In its simplest form, evolution is about changes in a species’ genetics over time. Each generation, small mutations might occur. If these mutations are beneficial—or at least not harmful enough to reduce survival—they can spread throughout the population.

Natural selection is often explained as “survival of the fittest,” but more precisely, it’s about reproductive success. Genes that lead to more offspring in the next generation can become widespread, while genes that reduce reproductive chances can fade out. Other forces, like genetic drift (random changes in gene frequencies) and gene flow (exchange of genes when populations migrate or intermix), add complexity to the evolutionary tapestry.

Yet, the question of whether we’ve “peaked” implies there’s some pinnacle or optimal state we could reach. Biology rarely works that way. Evolution is more like ongoing tinkering than building toward a final blueprint. Understanding this background helps clarify why humans continue to evolve, even if the exact path might differ from, say, early hunter-gatherer days.

Shifting from Nature’s Tests to Human-Made Environments

Reduced Mortality Pressures

In our ancestral past, everyday life carried enormous mortal risks. Predators, disease, famine, harsh climates—these pressures actively culled individuals who lacked suitable adaptations. Today, global vaccination programs, modern medicine, and stable food supplies mean many forms of natural selection are less intense. If you can treat a harmful genetic condition with medication, genes that once were detrimental might survive in the gene pool.

But does that mean evolution stalls? Not necessarily. Selection hasn’t disappeared; it has just changed its shape. Rather than large predators hunting us, we face novel pressures like pollution, sedentary lifestyles, and rampant processed foods. How these modern pressures impact our long-term genetic trajectory is still playing out.

The Role of Culture and Technology

Our species is particularly adept at cultural evolution—adapting through ideas, tools, and social structures. Over millennia, cultures have shaped genetic outcomes. For instance, the lactase persistence gene, which allows many adults of European, African, and certain Asian ancestries to digest lactose, spread in populations that domesticated cattle. Meanwhile, populations that didn’t rely on dairy have lower frequencies of lactose tolerance.

In the modern era, culture and technology can sidestep certain selective pressures. For example, eyeglasses help individuals with poor vision see perfectly well, so reduced eyesight is no longer a strong evolutionary disadvantage. Yet this cultural advantage might also lead us to wonder if certain biological traits become less tied to reproductive success, allowing genetic diversity to accumulate without the old rules of “adapt or perish.”

Are We Evolving More Slowly or Faster Than Before?

It’s natural to assume that because we’ve “engineered away” many old survival threats, we might be evolving more slowly. However, humans could actually be changing more quickly. Many scientists argue that population size plays a big role in the speed of evolution—more people means more total mutations. Each birth offers a new set of genetic shuffles.

Moreover, the past few thousand years have seen new selective forces arise, such as exposure to urban diseases, changes in diet, and even social pressures that affect who reproduces with whom. Some genetic markers in modern populations show signatures of recent selection. Certain immune system genes, for example, have been shaped by exposure to diseases like malaria or smallpox.

A Closer Look at Recent Adaptations

- High-altitude adaptation: Populations living in the Himalayas, Andes, or Ethiopian highlands have distinct oxygen-processing genes, giving them an advantage in low-oxygen conditions.

- Disease resistance: Some groups exposed to malaria over centuries developed genetic traits such as sickle cell variants, which in heterozygous carriers can confer resistance to malaria.

- Dietary adaptations: As mentioned, lactase persistence is a relatively recent adaptation, reflecting the spread of dairy farming.

These examples underscore that evolution isn’t just ancient history. It’s ongoing, albeit measured in generations, not single lifespans.

The Concept of an “Evolutionary Peak”

Talking about an “evolutionary peak” suggests an optimal design that can’t be improved upon. Yet biology is replete with trade-offs. A gene that’s beneficial in one context might be detrimental in another. Sickle cell variants, for instance, protect against malaria but can lead to sickle cell disease in homozygous carriers. The environment is always shifting, meaning the measure of “optimal” is perpetually in flux.

Many researchers see evolution as a dynamic arms race. Microbes, parasites, and viruses keep evolving, forcing our immune systems to adapt. Environmental conditions also change, sometimes rapidly. So even if we became “perfectly adapted” to a static environment, that environment rarely remains static. By the time we’ve “caught up,” something else shifts—climate, viruses, cultural norms, or technology.

Diagram: How Evolutionary Pathways Branch

Cultural Evolution vs. Biological Evolution

One tricky point is that we often conflate cultural evolution (the rapid spread of ideas, beliefs, and technologies) with biological evolution (changes in our genetic code). Cultural evolution can drastically reshape how we live within a few generations. Biological changes tend to be slower and more incremental.

Nevertheless, these two forms of evolution are tightly interwoven. A society might adopt agricultural practices that lead to dietary shifts, which then influence the prevalence of certain digestive enzymes. Or advanced medicine might allow individuals with genetic disorders to survive and reproduce, changing the overall gene pool’s composition. So while culture can blur or reroute certain evolutionary pathways, it doesn’t remove us from the game.

Environmental Factors Driving Evolutionary Change

Climate Instability

Climate is a major driver of genetic change. In the past, ice ages and warming periods forced humans to migrate and adapt. In some areas, it selected for shorter, stockier builds to conserve heat; in others, taller builds helped dissipate heat. Climate change today is happening faster than many historical shifts, though modern technology may cushion some of its direct impacts. Still, regional changes in temperature, precipitation, and extreme weather events could favor certain genetic traits—for instance, those related to heat tolerance or immune resilience against new pathogens.

Pollution and Toxins

We now live amid chemical exposure on a scale unknown in the past—plastics, industrial pollutants, microplastics in the ocean, air pollution in crowded cities, and more. Repeated exposure to toxins can spur physiological changes. If certain genes help detoxify or metabolize pollutants, those might become more common over many generations.

Pathogens and Antibiotic Resistance

Our immune systems remain under constant pressure from pathogens. While science fights a war against infectious diseases with vaccines and antibiotics, pathogens evolve rapidly (sometimes within days or weeks). Over the long term, humans might adapt as well. Consider how HIV shaped certain communities’ genetic makeup, or how repeated waves of influenza might gradually select for more robust immune responses.

The Future of Human Evolution

Will Genetic Engineering Overshadow Natural Selection?

In the not-too-distant future, genome editing technologies like CRISPR could allow us to alter our own genes deliberately. This bypasses the slow, random nature of mutation and selection. If such interventions become widespread, the course of evolution might pivot from naturally selected traits to engineered ones.

Imagine a scenario where prospective parents screen embryos for certain genes or correct harmful mutations. Over time, this could reshape humanity faster than any natural process. And if such “designer babies” become a reality for only certain populations, we might see genetic stratification that echoes today’s inequalities. Although this shifts evolution into a more deliberate domain, it doesn’t mean the processes that shaped us for millennia vanish; they simply take on a different flavor.

Space Colonization and Micro-Evolution

If humans establish off-world colonies, new environmental pressures could spark unique evolutionary paths. Settling on Mars, with its weaker gravity and radiation environment, could select for different bone density or immune responses. Over many generations, these settlers might diverge genetically from Earth-bound populations.

For instance, if living on Mars demands strict population management, only certain individuals might be allowed to reproduce, essentially creating a genetic bottleneck. This scenario leads us to wonder whether “Martian humans” could adapt so drastically that returning to Earth might feel like stepping into an alien world.

Could Modern Medicine Halt Evolution?

Medicine as a Double-Edged Sword

One common misconception is that advanced medicine and technology completely halt natural selection by removing the “survival of the fittest” effect. In reality, while medicine does protect us from many once-fatal conditions, it introduces new selective pressures and leaves room for subtle shifts.

- Longer Lifespans: People who once died young now survive and pass on their genes, potentially increasing the gene pool’s diversity.

- Lifestyle Diseases: Conditions like type 2 diabetes or heart disease could shape future adaptations if they become widespread enough to affect reproductive success or longevity.

- Reproductive Technologies: IVF (in vitro fertilization) and other fertility treatments can enable individuals with various genetic profiles to have children, potentially broadening genetic variation.

Social and Ethical Implications

Many of these medical innovations are socially regulated. Laws, religious beliefs, or economic factors can influence who accesses new health technologies and how. So the interplay between ethics and genetics can shift which traits get passed on, underscoring that evolution is never purely biological—it’s intertwined with human decision-making on multiple levels.

Myth-Busting: Common Misconceptions About Evolutionary Limits

Myth: We’re No Longer Evolving Because We Control Our Environment

Reality: While we do control many aspects of our environment, we haven’t completely negated selective forces. New pressures—be they infectious diseases, pollution, or social factors—continue to shape our genetics. Evolution doesn’t demand suffering or constant predatory danger; it just requires differences in reproductive success.

Myth: Evolution Has a Specific Goal or End Point

Reality: Evolution isn’t a conscious process aiming for a perfect form. It’s about what works well enough in the current environment to maximize the passing on of genes. When that environment changes—even slightly—there’s renewed potential for further adaptation.

Myth: Genetic Engineering Means the End of Natural Evolution

Reality: While gene-editing technologies may override some random processes, they won’t replace every facet of evolution. Errors, unforeseen consequences, and the relentless adaptation of diseases and microbes will continue shaping our genetics in the background. Moreover, not everyone may have access to gene editing, leaving parts of humanity still subject to traditional evolutionary pressures.

Where Are Our Brains Headed?

Another hot topic is whether our brains are still evolving. Over the past two million years, human brains tripled in size, enabling language, complex culture, and everything from tool use to rocket science. Are they still changing?

Some scientists suggest that modern society, with widespread information technology, might reduce certain ancestral cognitive skills (like memorizing large amounts of data) while fostering new ones (like navigating digital tools). Whether this results in genetic changes that shape brain structure is harder to pin down. Brain evolution could continue in subtle ways, perhaps reinforcing genetic pathways tied to problem-solving under digital stimuli. Alternatively, we might see new “offshoots” if populations diverge significantly in how they use and process technology.

Comparisons That Put Evolution in Perspective

For a tangible analogy, imagine Earth as a basketball and you’re perched on it. Evolution is like the slow, almost invisible shifting of your stance. If the ball changes shape—say it warms slightly or gains a texture—you’d adjust your stance to avoid falling off. Over a short time, you might not notice changes in your posture. But viewed over thousands of years, the stance you take on that basketball would look radically different.

Likewise, modern inventions act like cushions, sticky tape, or guard rails that help you stay secure on the ball. You might stand more comfortably in ways you never could before. But if the ball itself keeps changing shape, you’ll still adapt—just in new ways.

Genetic Variation: The Fuel That Keeps the Fire Burning

Regardless of how advanced we become, genetic variation remains the bedrock of evolution. Variation arises from mutations—random “copying errors” during DNA replication—as well as recombination when sperm and egg cells form. The bigger our global population, the more total mutations happen with each generation.

Not all mutations matter, of course. Most are neutral or even harmful. But beneficial ones—if they confer a reproductive advantage—can spread. The interplay of variation and selection is a delicate dance, influenced by human culture, environment, technology, and luck.

The Genetic Drift Factor

Genetic drift is the random fluctuation of gene frequencies, especially in small populations or isolated groups. While drift might not fundamentally “improve” or “worsen” traits, it can make rare genes more common by sheer chance. Think of it as rolling dice with each new generation. Small, isolated communities—like remote island populations—could evolve in directions quite different from the mainstream global population.

Social Pressures That Steer Our Gene Pool

Mate Selection and Changing Social Norms

In many societies, mate selection has shifted profoundly. Dating apps and global connectivity expand the pool of potential partners. Interracial marriages, once rare in some regions, are increasingly common, fostering gene flow across populations that were historically separate. This mixing could help homogenize certain traits or bring forth entirely new genetic combinations.

Conversely, in some cultures, arranged marriages or strict social norms still limit who can marry whom, reinforcing certain genetic lines. The result is a worldwide patchwork of different evolutionary paths, all happening in real time.

Economics, Power, and Reproduction

Humans aren’t strictly beholden to biology alone. Access to wealth, social status, or education can influence who has children and how many. For instance, some data show that in certain developed countries, people with advanced degrees have fewer children, while those in different socioeconomic groups might have more. Over generations, this interplay of economics and reproductive choices could subtly alter the gene pool.

Evolutionary Trade-Offs in Modern Times

The Obesity Epidemic

Modern lifestyles are often sedentary, and high-calorie foods are abundant. Our ancestors, facing food scarcity, stored energy effectively. Now, those same “thrifty genes” could predispose people to obesity and type 2 diabetes. If obesity significantly reduces fertility or survival in certain demographics, we might see natural selection gradually favor genes that better regulate metabolic processes.

Autoimmune Disorders

Improvements in public health mean fewer early-life infections. This could leave our immune systems “bored,” increasing the risk of autoimmune conditions (like allergies or asthma). If these conditions significantly impact reproductive success, or if medical science can’t fully manage them, we might see selection for genes that modulate immune responses more finely.

The Indirect Power of Human-Made Environments

Urban vs. Rural Lifestyles

There’s often a sharp contrast between urban and rural settings. Cities can be hotbeds of disease spread, but they also offer better access to healthcare, which can reduce the lethal impact of infections. Over time, the genes that thrive in crowded, polluted urban spaces might differ from those that thrive in sparse, agrarian settings.

Nutritional Profiles

Regions with different staple foods might inadvertently shape local genetic traits. For example, a diet high in maize without proper supplementation can lead to niacin deficiency (pellagra). Groups that have adapted to maize-based diets over centuries might show genetic tweaks aiding niacin uptake. This is analogous to how populations reliant on fish might adapt to glean more nutrients from seafood.

Where Technology Intersects With Evolution

Wearable and Implanted Devices

Think of hearing aids or pacemakers. These devices level the playing field, allowing people with certain health conditions to thrive. But if the genes associated with those conditions no longer reduce reproductive success, they remain in circulation. Meanwhile, we might see selection for traits that can better interface with advanced technology—like how well you handle constant digital stimuli or manage cybernetic enhancements if those become mainstream.

Artificial Intelligence Influences on Brain Use

As AI tools automate more tasks—from writing emails to diagnosing diseases—our cognitive environment changes. If certain individuals can adapt to or navigate AI-driven workflows more successfully, they might be socially and economically better off, potentially influencing reproductive patterns. It’s speculative, but it demonstrates how any large-scale technology could become an evolutionary factor.

The Big Picture: Evolution Is Here to Stay

Biologically, we never really “arrive” at a final destination. The question “Have we already peaked?” might stem from the misunderstanding that evolution is about progress toward a perfect being. But real evolution is about constant adaptation. So if there’s any conclusion to draw, it’s that humans are just as subject to evolutionary change as ever—only the details have shifted.

Rather than raging beasts in the wild, we face metabolic diseases, new viruses, fertility choices, and cultural norms. Instead of hunting for food with spears, we weigh nutritional labels in grocery stores. All these new contexts still influence which genetic variants stick around.

FAQ

Are humans evolving faster or slower than in the past?

It’s a mixed bag. While modern medicine reduces some lethal pressures, larger population sizes increase the total number of mutations. New selective forces (urban living, pollutants, new diseases) can also drive changes.

Could humans eventually split into multiple species?

It’s theoretically possible if populations become isolated and remain separate long enough for reproductive barriers to emerge. In reality, globalization and intermarriage make it unlikely in the near future.

Do we still have “survival of the fittest” in modern society?

Yes, but “fitness” in today’s world might be less about outrunning predators and more about thriving in modern conditions—resisting new diseases, managing stress, or adapting to technology.

Is there an upper limit on how large or complex our brains can get?

Biology imposes practical limits: a larger brain requires more energy, for example. Over time, trade-offs like childbirth constraints also play a role. But there’s no universal “cap” on brain evolution.

What role does climate change play in current human evolution?

It’s still unfolding. As climates shift, certain regions might face new disease vectors or changing food availability. Over generations, these factors could shape genes related to immunity and metabolism.

Will genetic engineering completely replace evolution?

Genetic engineering might overshadow some aspects of natural selection, but it’s unlikely to replace every evolutionary force, especially with pathogens and random mutations continually shaping our gene pool.

Why haven’t we noticed obvious new adaptations in modern humans?

Evolution requires multiple generations. We might only see distinct genetic changes in hindsight, after they’ve become widespread or particularly advantageous.

Could space travel speed up human evolution?

Space environments, with high radiation and low gravity, could accelerate selection for genes that cope with those stressors—especially if colonies remain relatively isolated for many generations.

Is there any chance we’ll become immune to all diseases?

Complete immunity is improbable. Pathogens evolve quickly, finding new ways to infect hosts. It’s a constant arms race, so while we might develop resistance to one threat, another can emerge.

Read More

- The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins

View on Amazon - Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari

View on Amazon - The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker

View on Amazon - Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond

View on Amazon - Nature (Peer-Reviewed Journal)

Visit Nature’s official website - Science (Peer-Reviewed Journal)

Visit Science’s official website

Humans may have advanced in unimaginable ways, but our genetic story continues. We might shape it with medicine, culture, or even CRISPR, yet at our core, we remain subject to evolution’s ceaseless push and pull. Far from peaking, our evolutionary dance is just taking on new steps.