TL;DR: Airplanes fly by balancing lift, thrust, drag, and weight, using specially shaped wings and engines to generate enough upward force to overcome gravity.

Why Lift Matters for Airplane Flight

When we talk about how airplanes fly, the first concept that usually comes up is lift. Lift is an upward force that opposes gravity. Without it, aircraft would never leave the ground.

Picture the wing of an airplane slicing through the air. Air hits the wing and is deflected around it, generating a pressure difference between the top and bottom surfaces. This difference produces lift, the force that pulls the plane skyward.

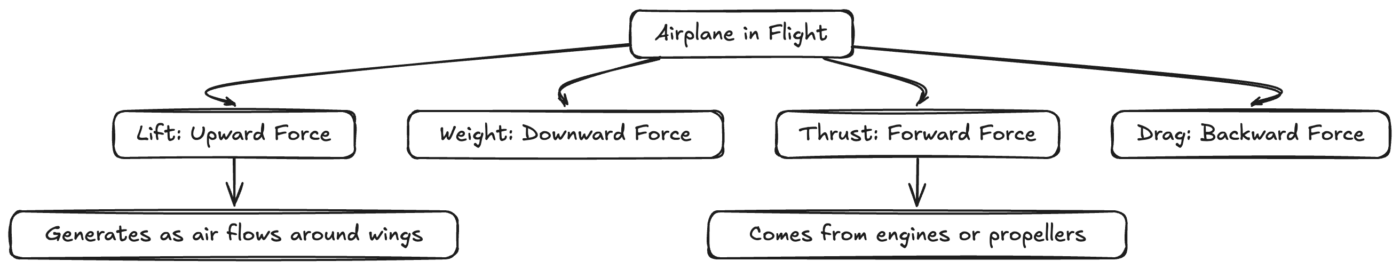

The Four Fundamental Forces

Flying wouldn’t be possible without considering four main forces acting on an airplane. These are:

- Lift: The upward force created mostly by the wings.

- Weight: The downward pull of gravity on the plane’s mass.

- Thrust: The forward force from engines or propellers.

- Drag: The resisting force from air friction and pressure.

If thrust is greater than drag, the plane moves forward. If lift exceeds weight, the plane climbs. Balancing these forces in different flight phases—takeoff, cruising, landing—is how pilots control altitude and speed.

Diagram: The Four Forces of Flight

Diagram: Highlights the four key forces acting on an airplane and how each contributes to flight.

Airfoils: The Shape That Makes Wings Work

An airfoil is the cross-sectional shape of a wing, specifically designed to create efficient lift. If you slice a wing and look at its outline, you’ll notice it usually has a curved upper surface and flatter lower surface.

This curvature helps air move faster over the top of the wing and slightly slower underneath. Faster airflow on top leads to lower air pressure. Slower airflow on the bottom means higher air pressure. The resulting pressure difference supplies the upward push we call lift.

Bernoulli’s Principle vs. Newton’s Laws

When explaining flight, two major scientific ideas often pop up: Bernoulli’s principle and Newton’s laws.

Bernoulli’s principle states that faster-moving fluid (like air) has lower pressure than slower-moving fluid. Because airflow on top of the wing speeds up, pressure there drops. Meanwhile, pressure below the wing is higher, pushing the wing up.

Newton’s laws—especially the third law (every action has an equal and opposite reaction)—offer a more direct explanation: the wing deflects air downward, so the airplane experiences an equal upward force. Both explanations are valid. Wings can generate lift from a combination of pressure differences (Bernoulli) and downward deflection (Newton).

The Angle of Attack

The angle of attack is the angle between the wing’s chord line (an imaginary line from the wing’s leading edge to its trailing edge) and the relative wind (the airflow hitting the wing). If you tilt a wing upward just right, you produce more lift by deflecting more air downward.

However, increasing the angle of attack too much leads to stall, a sudden drop in lift when airflow separates from the wing’s upper surface. Pilots constantly monitor angle of attack to balance enough lift without risking a stall, especially during takeoff and landing.

Engines and Thrust Generation

Airplanes need thrust to move forward. Turbofan engines (common on commercial jets) suck in air, compress it, mix it with fuel, and ignite the mixture. The expanding gases shoot out the back, propelling the plane forward in a classic demonstration of Newton’s third law.

Smaller aircraft often use propellers powered by piston or turboprop engines. The propeller’s spinning blades accelerate air backward, creating forward thrust. In either case, the key is to push air in one direction to move the plane in the opposite direction.

Balancing Weight with Lift

Even if an airplane’s wings generate lift, there’s always weight pulling down due to gravity. The plane’s total weight includes the fuselage, passengers, cargo, and fuel. It’s crucial that lift meets or exceeds weight, especially during takeoff.

As an airplane burns fuel, its weight decreases slightly, making it easier to stay aloft at higher altitudes. Pilots use flaps, slats, and other control surfaces to alter the wing’s shape and increase lift when needed, like during the slower phases of flight (takeoff, approach, landing).

Drag: The Ever-Present Opponent

Drag is any force resisting the airplane’s motion through air. It has two main components:

- Parasite Drag: Created by the shape of the plane, friction of air over surfaces, and anything sticking out into the airflow (like antennas).

- Induced Drag: Directly related to lift production. Higher lift generally means higher induced drag.

Engineers try to reduce drag through streamlined designs—smooth fuselages, curved wingtips—because less drag means less fuel burned and higher efficiency.

Dihedral, Anhedral, and Wing Placement

Look closely at many airplanes, and you’ll see the wings might angle slightly upward (called dihedral) or downward (anhedral). Dihedral helps the aircraft stay stable by naturally rolling back to level if it’s tilted. Anhedral is sometimes used for certain military jets to improve maneuverability.

Where the wing is placed on the fuselage—high-wing, mid-wing, or low-wing—also affects stability, landing gear design, and cockpit visibility.

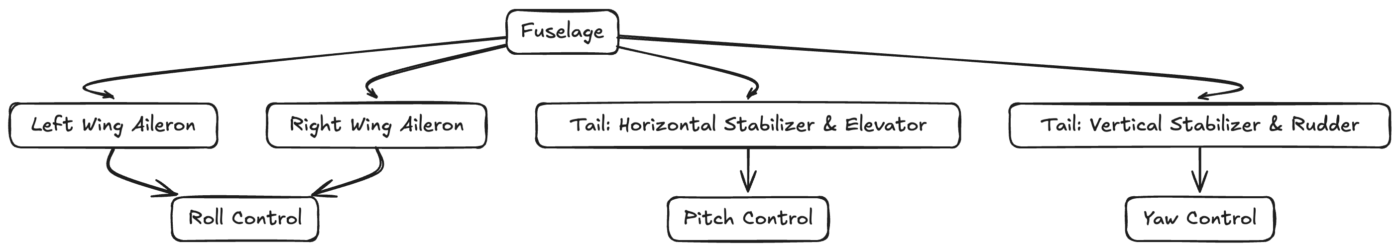

Flight Controls: Ailerons, Elevators, and Rudder

Pilots don’t just rely on the wings’ shape. They also manipulate control surfaces:

- Ailerons: Hinged sections on the trailing edge of the wings. Move them up or down to roll the plane left or right.

- Elevators: On the horizontal tail, controlling the plane’s pitch (nose up or down).

- Rudder: On the vertical tail, steering the plane’s yaw (nose left or right).

These surfaces direct airflow, giving the pilot precise authority over the plane’s orientation in 3D space.

Diagram: Airplane Control Surfaces

Diagram: Shows the main control surfaces on an airplane and their associated motions.

Why Airplanes Climb or Descend

When a pilot wants to climb, they pull back on the control column, raising the nose. This increases the angle of attack, thereby increasing lift—if there’s enough thrust to maintain or gain speed. Conversely, to descend, you lower the nose, reducing lift slightly so that weight overcomes the upward force.

Pilots also adjust engine power. More thrust can compensate for extra drag from a higher angle of attack. Less thrust means the plane might lose speed if the angle remains too high.

Altitude and Air Density

At higher altitudes, the air is thinner (lower pressure), so wings generate less lift at the same speed. Engines also get less oxygen, affecting power output. Aircraft operating in thin air must fly faster to produce the same amount of lift or use bigger wings. This is why many commercial jets cruise at 800-900 km/h (500-560 mph) at altitudes of around 10-12 km (33,000-39,000 ft).

Different Wing Designs for Different Missions

Not all wings look alike. Gliders often feature very long, slender wings to maximize lift and minimize drag. Fighter jets have short, swept-back wings for speed and agility. Cargo planes might employ large wings with high-lift devices to handle heavy payloads during takeoff and landing.

Each design reflects a compromise among speed, maneuverability, payload capacity, and fuel efficiency.

Jet Engines vs. Propellers

Some airplanes rely on propellers to push air backward. Others use jet engines (turbofans, turbojets). Jet engines are generally faster, more efficient at high altitudes, and can produce greater thrust.

Propeller-driven planes, on the other hand, are well-suited for shorter distances, lower speeds, and smaller runways. They’re often quieter and cheaper to operate, making them popular for regional flights or private planes.

Supersonic Flight: Breaking the Sound Barrier

When an aircraft travels faster than the speed of sound (~1234 km/h or 767 mph at sea level), it enters supersonic flight. Shock waves form around the plane, causing a sonic boom. To handle supersonic speeds, airplanes require streamlined shapes, specialized materials, and wings that can operate efficiently at high Mach numbers.

Classic examples include the Concorde and military fighters like the F-16. Managing supersonic airflow demands advanced aerodynamics to mitigate extreme drag and heating.

Myth-Busting: “Wings Must Be Curved on Top to Fly”

Myth

A persistent myth is that wings only work due to their curved top surface forcing air to travel a longer path, thus creating lift.

Reality

While curvature (the camber) is important, a flat or even slightly concave wing can still generate lift with the right angle of attack. Many aerobatic planes and supersonic jets have almost symmetrical wing cross-sections. They rely on adjusting the angle of attack to push air downward and create an opposite upward force.

Myth-Busting: “Airplanes Float on Air Currents”

Myth

Another misconception suggests airplanes merely ride on rising air or updrafts like a kite or bird.

Reality

Although gliders and soaring birds do exploit thermals or ridge lift, powered aircraft primarily rely on engine thrust and wing lift to stay airborne. Updrafts can help reduce fuel usage or gain altitude, but airplanes don’t depend on them for normal cruising flight.

Stability: Static vs. Dynamic

Airplanes are designed for static stability—if disturbed (e.g., a gust of wind tilts the wings), the plane tends to self-correct. Dynamic stability means the corrections over time don’t amplify into bigger oscillations.

Engineers adjust center of gravity, wing position, and the design of tail surfaces to ensure the plane doesn’t become overly sensitive or dangerously sluggish.

Flaps, Slats, and Other High-Lift Devices

During takeoff and landing, aircraft need extra lift at lower speeds. Flaps (at the trailing edge of the wing) and slats (at the leading edge) can extend and change the wing’s curvature. This creates more lift while also increasing drag. Pilots carefully deploy these devices to ensure safe lift generation during slower flight phases.

Avionics and Fly-by-Wire Systems

Modern jets rely on avionics—electronic systems integrating navigation, communication, and flight control. Fly-by-wire means the pilot’s inputs go through computers, which send electronic signals to move the control surfaces. The system can apply corrections almost instantly, helping maintain stability and reduce pilot workload.

Vertical Takeoff and Landing (VTOL)

Some specialized aircraft, like helicopters or Harrier jets, can take off and land vertically. They generate lift using rotating blades (in helicopters) or thrust-vectoring nozzles (in jets), directing engine exhaust downward to counteract weight. While these designs are highly flexible for short runways, they’re usually less fuel-efficient than conventional airplanes in forward flight.

Gliding and Engine-Out Scenarios

When an airplane’s engines fail, it doesn’t fall straight down. Pilots can still control a “dead-stick” landing by gliding, using the remaining airflow over the wings to maintain partial lift. The plane will descend gradually, but skillful pilots can choose a safe landing spot in many cases.

Even large commercial jets can glide for significant distances if all engines fail, giving the crew time to attempt restarts or find a suitable runway.

Jet Streams and Efficient Routes

High-altitude winds called jet streams can exceed 160 km/h (100 mph) or more. Pilots often plan routes to take advantage of tailwinds or avoid strong headwinds, saving fuel and time. These winds shift with season and latitude, so flight planning software constantly updates recommended paths.

The Magic of Winglets

Most modern jetliners feature winglets at the wing tips—small vertical or angled surfaces. Winglets reduce the vortex (rotating air) that forms at the tip, cutting induced drag. Less induced drag means better fuel efficiency and longer range.

This design element was inspired by both nature (some birds have tip feathers angled upward) and wind-tunnel experiments in the 1970s. Winglets can boost efficiency by a few percent—a huge difference in aviation economics.

The Critical Role of Airspeed

An airplane must maintain a minimum airspeed to generate enough lift to counteract its weight. This speed is called stall speed. If the plane falls below this threshold, it risks stalling, losing lift rapidly. That’s why takeoff and landing speeds are carefully calculated based on weight, altitude, runway length, and weather.

Fuel Efficiency and Aircraft Design

Airlines care deeply about fuel burn and operating costs. Larger aircraft typically have more efficient wings—like the high-aspect-ratio wings found on Boeing 787 or Airbus A350. Lightweight materials, advanced engine technology, and aerodynamic tweaks all contribute to better efficiency.

Pressure Cabins and High-Altitude Cruising

Commercial jets often cruise near 10-12 km (33,000-39,000 ft). The thinner air up there has less drag, improving fuel economy. Because outside air pressure is too low for humans, cabins are pressurized using engine bleed air. This ensures safe oxygen levels and comfortable conditions for passengers.

Aircraft Icing and Weather Effects

Flying through cold, wet conditions can lead to ice buildup on wings. Ice disrupts smooth airflow, raising drag and lowering lift. Modern planes have de-icing systems—like heated wing edges or inflatable boots—that remove or prevent ice accumulation. Strong weather can also cause turbulence or wind shear, challenging pilots to adjust quickly while ensuring passenger comfort.

Landing Gear, Brakes, and Reverse Thrust

Landing isn’t just about descending. Planes must slow down on the runway. The landing gear extends, creating drag, while wheels with advanced brake systems absorb the plane’s forward momentum.

Some aircraft also use reverse thrust—directing engine exhaust forward—to help decelerate. On shorter runways or wet surfaces, these methods are critical for stopping safely.

Autopilot and Automated Flight Systems

Autopilot systems can handle level flight, headings, and even automatic landings under certain conditions. Pilots remain in control, overseeing the systems, but automation reduces fatigue and risk of human error. Advanced systems can also manage approach paths, check flight parameters, and quickly adapt to changing conditions.

A Peek at Future Aviation Technologies

Looking ahead, engineers explore:

- Electric Planes: Using battery-powered motors for short commuter flights.

- Hybrid-Electric: Combining batteries with conventional fuel for reduced emissions.

- Hydrogen Fuel: Potentially zero CO₂ emissions if hydrogen is green-produced.

- Supersonic Rebirth: New designs to bring back faster-than-sound passenger travel more quietly and efficiently.

Each innovation targets lower environmental impact, improved speed, or expanded operational flexibility.

FAQ Section

What keeps planes in the air?

They’re kept aloft by lift, generated primarily by the wings. As air flows around the wing’s shape, lower pressure above and higher pressure below create an upward net force.

How do airplanes turn?

Pilots roll the plane with ailerons, so lift tilts to one side, causing a banked turn. They can also use the rudder to fine-tune yaw, ensuring a coordinated turn.

Why don’t planes just fall when engines fail?

They can glide—the wings still produce lift as long as there’s forward airspeed. Pilots practice engine-out scenarios to land safely in emergencies.

How do pilots avoid collisions?

Air traffic control systems coordinate flight paths and altitudes, plus onboard collision avoidance systems track nearby aircraft. Pilots also follow strict regulations and routes.

Do planes really need long runways?

Yes. They must accelerate to a speed above stall speed, plus have extra safety margin. More runway length provides room for takeoff or aborted takeoff if something goes wrong.

Key Takeaways

- Lift is the critical force that pushes planes up, generated by the wing’s shape and angle of attack.

- Thrust from engines or propellers overcomes drag, keeping the plane moving forward.

- Balancing the four forces—lift, weight, thrust, and drag—is crucial for stable flight.

- Control surfaces (ailerons, elevators, rudder) let pilots maneuver in three dimensions.

- Factors like angle of attack, wing design, air density, and engine power all contribute to whether and how a plane flies.

Final Thoughts on How Airplanes Fly

Airplanes combine aerodynamics, engineering, and physics to accomplish something truly remarkable: stable, controllable flight. The magic lies in harnessing airflow across a wing, generating enough lift to counteract weight, and pushing forward against drag with engine thrust.

From the moment the Wright brothers first took flight, aviation has soared thanks to refinements in design, better engines, and deeper understandings of airflow. Whether it’s a single-propeller crop duster or a massive intercontinental jetliner, the core principles remain the same—use the shape of the wing, manage forces carefully, and keep the air beneath you in motion.

As technology races ahead, we’ll likely see new materials, propulsion systems, and control methods. Yet the essence of flight—making air molecules flow in just the right way—will continue to guide engineers and pilots for generations to come.

Read More

- Stick and Rudder by Wolfgang Langewiesche (Amazon)

- Theory of Flight by Richard Von Mises (Amazon)

- Aerodynamics for Naval Aviators by H.H. Hurt Jr. (Amazon)

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

- NASA Aeronautics Research

These resources delve further into flight principles, aircraft design, and the evolving future of aviation. Enjoy exploring the fascinating world that lifts us above the clouds.