TL;DR: The placebo effect can strongly influence medical outcomes, harnessing the power of belief to trigger measurable biological changes.

The placebo effect is more than just a mysterious quirk of medical research. It’s a phenomenon where simply believing a treatment works can create tangible improvements in how we feel.

Scientists have spent decades uncovering how our mind’s expectations, conditioning, and social cues can alter physiology, shedding light on a curious question: How powerful can mere belief be?

Below, we’ll explore the psychological and biological mechanisms of the placebo effect, unravel common myths, and look at its ethical implications in modern medicine.

We’ll also dive into how it surfaces across various health conditions, from pain management to mental health. So let’s get started and see just how deeply the mind can influence the body.

Understanding the Placebo Effect

When we say a treatment is a “placebo,” we generally mean it’s inactive, lacking a therapeutic ingredient that directly addresses a health problem. Yet in countless experiments, patients given placebos can experience real relief.

In a typical drug trial, scientists compare an active drug to a placebo. If the drug outperforms the placebo, we conclude that its effects are genuine. But across a range of conditions—from headaches to anxiety—placebo groups often show measurable improvements. This shift isn’t simply “in people’s heads”; it can be reflected in changes to blood pressure, hormone levels, and even the activation patterns in the brain.

Researchers define the placebo response as any change in a patient’s condition that arises from their expectation that they’ve received an effective treatment. This expectation can be powerful, triggering neurological pathways similar to those activated by real pharmacological agents. In other words, the body sometimes responds to a belief the same way it responds to an actual drug.

The Role of Expectation and Conditioning

A crucial driver of the placebo effect is expectation. When a doctor confidently says, “This treatment could help,” our brains can release neurotransmitters that reduce pain or influence other bodily processes. It’s akin to a self-fulfilling prophecy: if we believe something will help us, our physiology may align with that belief.

Another core mechanism is classical conditioning—familiar from Pavlov’s dog experiments. Over time, taking pills that actually contain medicine can build an association in our brains between swallowing a capsule and feeling relief. A placebo pill can then trigger the body’s memory of relief, even if it contains no active substance.

Historical Roots

The idea of beneficial “sham” treatments isn’t new. In ancient cultures, healers often relied on rituals, incantations, or inert substances to alleviate distress. These traditions highlight how ritualistic aspects—like the color of a pill or the setting of a clinic—can strengthen belief and thus boost the placebo effect.

Today, placebos serve as benchmarks in clinical trials. But their role extends beyond lab studies. Some physicians discuss the possibility of using placebos in actual practice to harness the mind’s healing potential, although this raises a host of ethical questions we’ll explore later.

The Mind-Body Connection: How Belief Shapes Biology

Beliefs may seem intangible, but they can launch biochemical cascades that affect heart rate, immune response, and perception of pain. Neuroimaging studies show that expecting pain relief can cause the release of endorphins and other endogenous opioids in the brain—molecules that act a lot like morphine.

Brain Networks at Play

Research using functional MRI (fMRI) reveals that during a placebo response, areas of the brain associated with pain processing—like the anterior cingulate cortex—become less active. Simultaneously, regions that manage emotions and reward expectations, such as the prefrontal cortex, can kick into high gear.

What’s exciting is that these brain patterns mirror what happens when we take real analgesics. In essence, the placebo effect can mimic the biological pathways of an active drug, reinforcing the idea that our mind’s expectations can tap into powerful healing mechanisms.

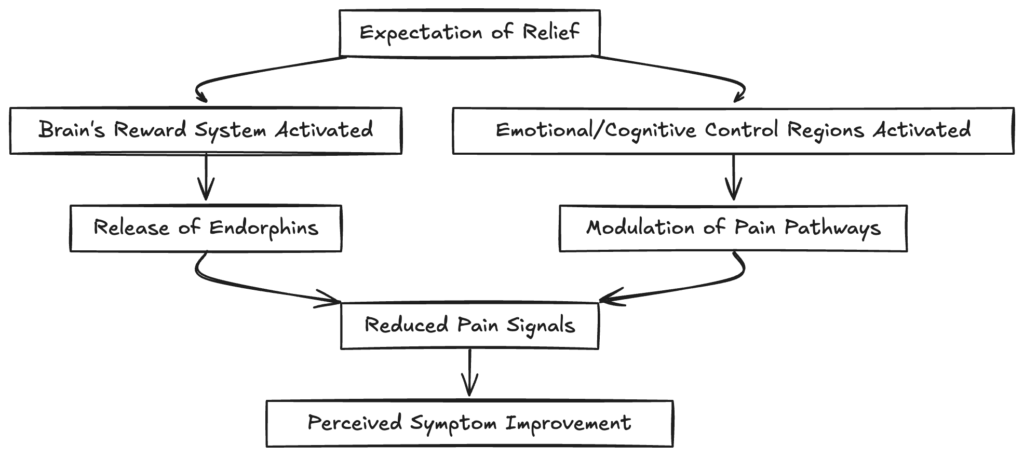

Diagram: Placebo-Induced Brain Changes

In this schematic, an expectation of relief can trigger the brain’s reward system, prompting the release of endorphins. Meanwhile, heightened activity in emotional and cognitive control regions can further modulate pain pathways, ultimately reducing the subjective experience of discomfort.

Stress Hormones and Immune Function

Stress is a major driver of poor health. Elevated levels of cortisol (often called the stress hormone) can weaken immune responses and slow healing. Positive expectations can help lower stress hormones, contributing to better immune function and possibly faster recovery times.

Think of it like dropping tension from your shoulders. The body can shift resources from stress mode to healing mode when it senses relief is on the way—even if that relief is triggered by a sham treatment.

Real-World Impact and Clinical Trials

Many clinical trials illustrate the placebo effect’s magnitude. In studies on pain relief, for instance, patients receiving placebos often show significant improvement compared to no-treatment controls. Sometimes, the difference between placebo and an actual drug is surprisingly small.

Case Study: Placebos for Pain

In one landmark study, patients with post-surgical pain were given injections of saline but told they were receiving potent painkillers. A substantial portion reported relief comparable to those who received actual analgesics. When the patients were secretly switched from real pain medication to saline, many continued to feel pain relief—until they were informed of the switch, at which point the relief faded.

Placebos vs. Active Drugs

Most new therapies are tested against a placebo. If a novel drug only outperforms the placebo by a small margin, the drug is often considered less effective. This standard underscores how powerful placebo responses can be. A drug has to do more than just reassure patients—it must surpass the physiological and psychological benefits arising purely from expectation.

Placebo Surgery

A dramatic example is “placebo surgery,” in which patients undergo sham procedures—an incision or minimal manipulation—without the actual surgical intervention. In some controlled trials for knee pain or spine conditions, patients receiving sham surgery reported improvements on par with those who got real procedures. Although these findings are controversial, they highlight the sweeping influence of the mind in shaping post-operative outcomes.

Mechanisms Behind the Placebo Effect

To understand exactly how placebos can lead to real physiological changes, we need to look at a few core mechanisms. These range from neurotransmitter release to hormonal adjustments and learned responses shaped by a patient’s past experiences.

Neurotransmitter Systems

The human brain is a biochemical powerhouse, with dopamine, endorphins, and various other neurotransmitters influencing mood, pain, and immune function. Placebos can nudge these systems into action.

For example, in the realm of Parkinson’s disease, a condition where patients have low dopamine levels, placebos have been found to boost dopamine release, temporarily improving motor function.

Opioid and Non-Opioid Pathways

While endorphin release is often associated with the placebo effect in pain management, some placebo responses don’t rely on opioid systems at all. In certain studies, using opioid-blocking drugs (like naloxone) eliminated placebo-induced pain relief in some subjects, but not in others. This points to additional, non-opioid mechanisms—like endocannabinoid pathways—contributing to the effect.

Conditioning and Ritual

Healthcare settings are full of rituals: the doctor’s white coat, the smell of antiseptic, the sight of medical equipment. Each element can reinforce a patient’s belief in the potency of a treatment. Over time, these signals condition the brain to expect relief or healing.

In the same way Pavlov’s dogs learned to associate a bell with food, patients may come to associate these clinical cues with recovery. Placebos capitalize on these unconscious associations, effectively turning an inert pill into a conditioned stimulus that triggers a healing response.

The Placebo Effect Across Different Conditions

Not all ailments respond equally to placebos. Generally, subjective symptoms—such as pain, nausea, or depression—tend to be more placebo-responsive than conditions requiring direct biochemical interventions, like bacterial infections or tumors. However, some studies suggest that the placebo effect can boost immune function, potentially influencing more objective measures over time.

Pain and Analgesia

Pain is perhaps the most studied area. Multiple analyses confirm that placebos can significantly ease discomfort, sometimes achieving results close to standard analgesics. This might involve distracting the brain or prompting the release of pain-modulating neurotransmitters.

Depression and Anxiety

In clinical trials of antidepressants, placebo responses can be notably high. Depressive symptoms, deeply entwined with our emotional state, can be influenced by hope, social support, and therapeutic rituals. While active medications often outperform placebos, the relatively high placebo success rate underscores how patient expectations and doctor-patient rapport can shape mental health outcomes.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) show strong placebo responsiveness. Gut function is closely tied to stress, emotion, and the autonomic nervous system—all areas highly susceptible to positive or negative beliefs. Even placebo acupuncture (using retractable needles that never actually penetrate the skin) can alleviate IBS symptoms for some patients.

Immune Responses

Although more controversial, some evidence suggests that immune parameters—like antibody production—might be enhanced under positive expectations. The effect isn’t as straightforward or dramatic as in pain management, but it hints that mind-driven changes could extend to immune function in subtle ways.

Ethical Dimensions in Placebo Use

If placebos can help people feel better, should doctors prescribe them deliberately? The question is complex. Deception is often central to a placebo’s efficacy. Telling a patient, “This pill is inert” usually reduces the beneficial impact. Yet deceiving patients conflicts with informed consent and medical ethics.

Open-Label Placebos

In recent years, researchers explored open-label placebos—where patients are told they’re receiving an inert pill, yet are also told about its potential beneficial effects. Surprisingly, some studies on chronic pain or IBS show improvements even when patients know they’re on a placebo. This finding suggests that some mechanism beyond simple deception—perhaps ritual, conditioned reflexes, or the mere act of caring—can provide benefit.

Balancing Hope and Honesty

From an ethical standpoint, many argue that harnessing the placebo effect responsibly requires transparency. Physicians must walk a tightrope between instilling hope and being truthful. As research progresses, we may discover ways to ethically leverage patient expectation without resorting to blatant falsehoods.

Informed Consent in Clinical Trials

The cornerstone of modern clinical research is informed consent, where participants must know they could receive a placebo instead of an active treatment. This expectation can shape their mindset—some might become hyperaware of changes in their bodies, ironically amplifying the placebo or nocebo effect (where negative expectations worsen symptoms). Researchers design double-blind trials to reduce these biases, but the interplay of mind and body remains inescapable.

The Future of Placebo Research

Placebo science is evolving rapidly. Advances in neuroimaging, genetics, and psychology enable researchers to decode the placebo effect with increasing sophistication. We’re gaining insights into why some individuals are more placebo-responsive than others, and how to harness these insights without misleading patients.

Genetic Markers of Placebo Response

Certain genetic variations may predict how susceptible a person is to placebos. For instance, variations in genes related to dopamine or serotonin signaling could enhance or diminish the mind’s capacity to generate a placebo-driven improvement. Identifying these markers might help clinicians tailor treatments to individual patients.

Personalized Medicine and Integrative Care

As we lean toward personalized medicine, the placebo effect could become a recognized asset rather than a nuisance. Incorporating elements of holistic care, mindfulness, and therapeutic suggestion might optimize the healing environment. If a patient’s mindset can be harnessed ethically, practitioners could amplify positive outcomes alongside standard treatments.

Tech-Based Placebos

Innovations in digital health might create new forms of placebo. Mobile apps offering guided imagery or interactive “treatments” could mimic clinical cues. Virtual reality (VR) programs, for instance, are already tested for pain relief and mental health support. Even if these programs lack active medical ingredients, they can help modulate patients’ symptoms by engaging the same psychological pathways that placebos do.

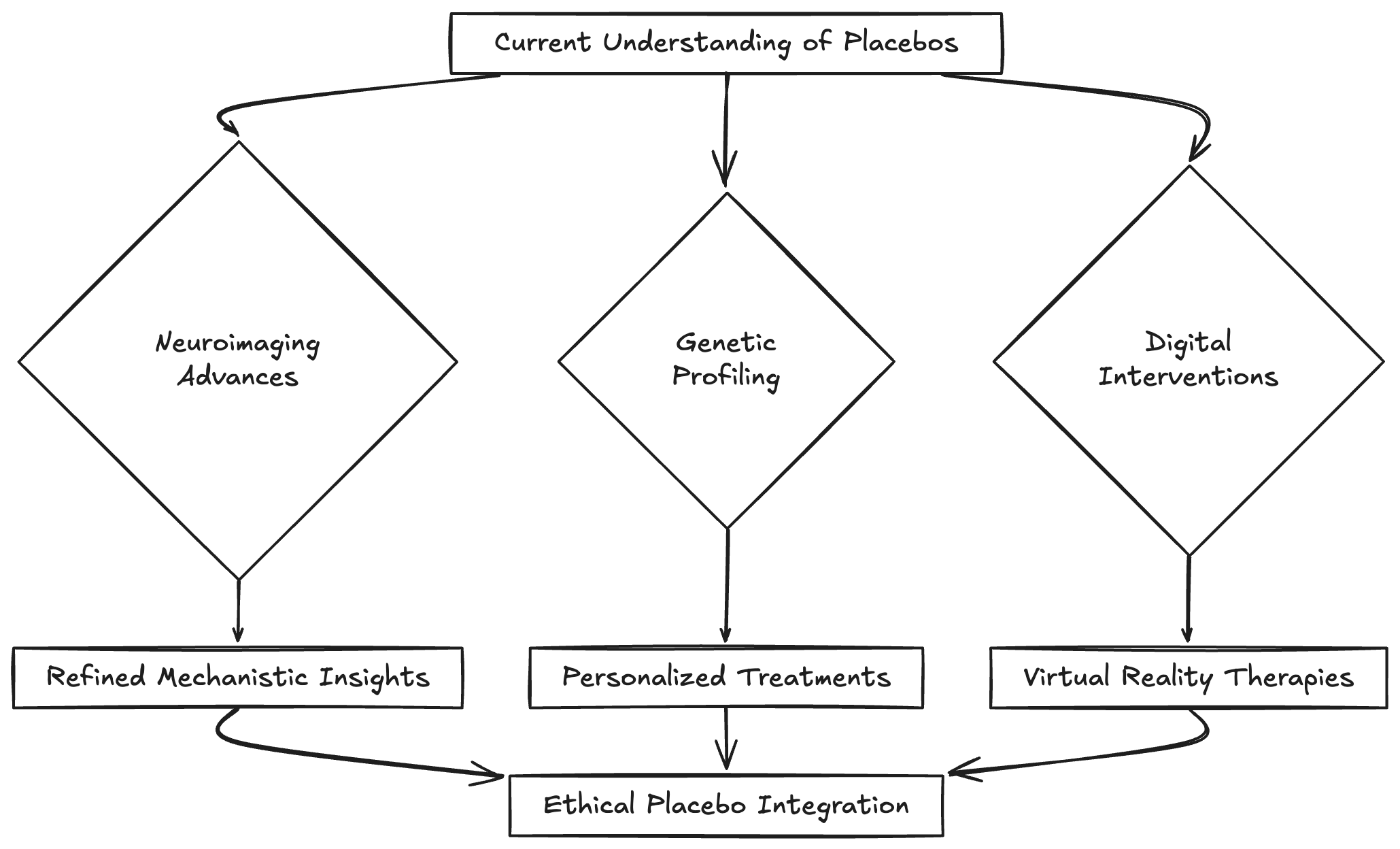

Diagram: Potential Future Paths of Placebo Research

Diagram: Future Directions in Placebo Research

We see how neuroimaging advances, genetic profiling, and digital interventions converge to yield refined mechanistic insights, personalized treatments, and VR-based therapies. These developments, in turn, could lead to more ethical placebo integration in mainstream medicine.

Myth-Busting the Placebo Effect

Myth: The Placebo Effect Is All in Your Head

Reality: While it starts with belief, the placebo effect triggers real, measurable changes—like endorphin release and shifts in brain activity. It may begin in the mind, but it doesn’t stay there.

Myth: Anyone Who Responds to a Placebo Must Be Gullible

Reality: Placebo responsiveness isn’t about naivety. Even people well-versed in science experience placebo benefits. It’s partly hardwired into how our brain-body system works.

Myth: Placebos Work for Every Condition

Reality: Conditions involving subjective experiences (like pain, anxiety) often see strong placebo responses. While some evidence suggests a broader reach, placebos aren’t a magic wand for all ailments—especially those requiring direct biochemical intervention, like severe infections.

Myth: Placebo Effects Are Too Small to Be Clinically Relevant

Reality: In many clinical trials, placebos lead to moderate or even substantial improvements. Sometimes, the difference between a new drug and a placebo is small, emphasizing how impactful expectancy alone can be.

Myth: You Must Lie to Harness the Placebo Effect

Reality: Open-label placebos are shaking up this assumption. Patients told they’re receiving a “non-active” pill still report relief, suggesting transparency can coexist with the power of belief.

Relatable Comparisons: The Placebo Effect in Everyday Life

To understand just how subtle the placebo effect can be, compare it to having a lucky charm. People might wear a special necklace they believe boosts their confidence. Logically, the necklace has no innate power—yet the person’s performance might genuinely improve because their stress levels drop and they feel more optimistic.

If Earth were the size of a basketball, the distance from the mind to the body is basically zero. They’re deeply interconnected. In that sense, the placebo effect is like pressing a small button (belief) that can initiate big, surprising changes (physiological shifts) inside that basketball.

Common Sidekick: The Nocebo Effect

It’s worth noting that belief can harm as well as heal. The nocebo effect occurs when negative expectations worsen symptoms. For instance, if patients expect a medication’s side effects, they might feel them more intensely—even if they’re on a placebo. This darker twin of the placebo effect illustrates how powerful our mindset can be in shaping health outcomes.

FAQ

What exactly is a placebo?

A placebo is typically an inert substance (like a sugar pill or saline solution) used in clinical trials to compare with an active treatment. Its effectiveness relies on the patient’s expectation of benefit rather than any direct biochemical action.

How does the placebo effect work?

It’s driven by expectation, conditioning, and contextual cues. The mind’s belief in a treatment triggers chemical and neural changes, such as endorphin release, leading to real physiological shifts.

Can the placebo effect cure serious illnesses?

While placebos can ease symptoms (pain, anxiety, etc.), they usually can’t cure major conditions like cancer. They may, however, improve quality of life or complement other treatments.

Is it unethical for doctors to use placebos?

Deception poses ethical concerns. However, open-label placebos—where patients know they’re getting a placebo but still benefit—are emerging as a potential compromise that respects informed consent.

Do all people respond equally to placebos?

No. Genetic factors, personality traits, and cultural influences can affect placebo responsiveness. Some individuals may exhibit larger effects than others.

Can placebos have side effects?

Yes, through the nocebo effect. If a person believes they’ll experience negative outcomes (like headaches or nausea), they may indeed feel these symptoms—even from an inert substance.

Are there any risks to relying on the placebo effect?

Relying solely on placebos for serious conditions might delay proper treatment and can be dangerous. Placebos work best alongside evidence-based medical care, not as a standalone cure.

Are there objective tests to measure placebo responses?

Scientists use neuroimaging, physiological markers (like heart rate or hormone levels), and patient-reported outcomes. Double-blind trials help differentiate true placebo responses from other factors.

Do placebos work if we know they’re placebos?

Surprisingly, yes. Studies show open-label placebos can still trigger symptom improvement, possibly due to the supportive clinical environment and conditioned brain responses.

How widespread is placebo research?

It’s a growing field. Many neurologists, psychologists, and medical researchers study placebos to enhance treatments and improve patient well-being without resorting to unethical deception.

Read More

- The Placebo Response: How Words and Rituals Change the Brain by Fabrizio Benedetti

View on Amazon - Suggestible You: The Curious Science of Your Brain’s Ability to Deceive, Transform, and Heal by Erik Vance

View on Amazon - Mind Over Medicine: Scientific Proof That You Can Heal Yourself by Lissa Rankin

View on Amazon - Harvard Health Publishing – Official Website

- Nature (Peer-Reviewed Journal) – Visit Nature’s official website

- The Lancet (Peer-Reviewed Journal) – Visit The Lancet’s official website

In the end, the placebo effect is a striking testament to the synergy between mind and body. Though it can’t replace proven medical interventions, it can amplify the healing process, ease symptoms, and remind us that belief plays a crucial role in our overall well-being.

By integrating the placebo effect ethically and transparently into patient care—through supportive environments, open communication, and respect for informed consent—we may continue to harness this profound mind-body phenomenon. And as research pushes forward, our understanding of how expectations shape biology could unlock new possibilities for healing and patient support.