TL;DR: Heat converts the moisture inside a popcorn kernel into steam, building pressure until the hull bursts and the starchy interior puffs into a crunchy, delicious flake.

Popcorn may look simple, but its unique ability to pop hinges on a combination of moisture, starch, and a sturdy outer shell. Each kernel of popcorn contains a precise ratio of moisture (typically around 13-14%) sealed inside a strong hull, along with ample starch that provides the raw material for the fluffy texture.

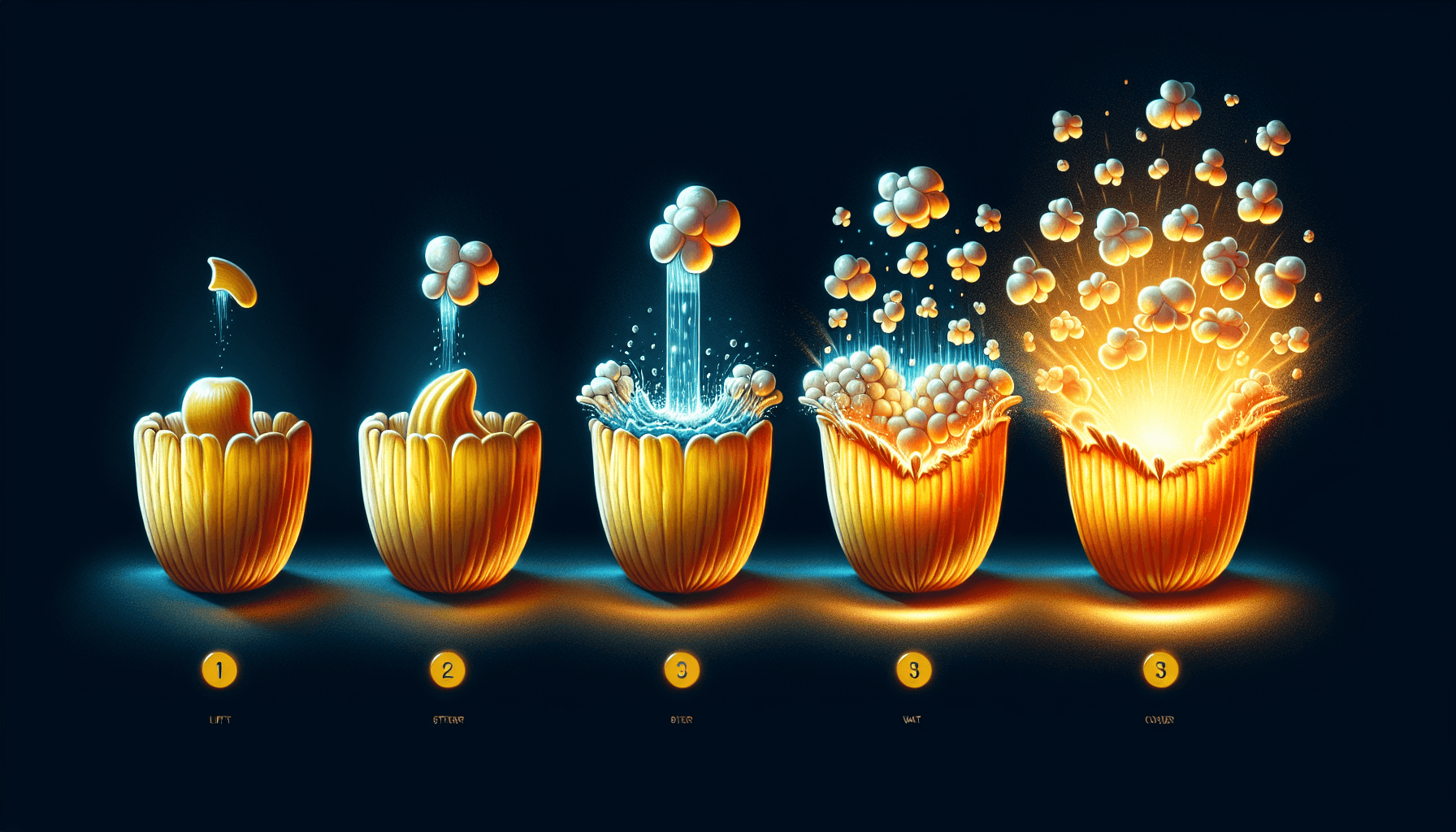

When you heat a kernel, its internal water vaporizes into steam. Because the kernel’s hull is relatively impermeable, the steam can’t escape right away, so the pressure builds up rapidly. Eventually, the hull can no longer contain this force, causing a spectacular mini-explosion that unravels the kernel’s starchy interior. It’s a remarkable natural process—one that only a specific variety of corn can achieve.

In the next sections, we’ll explore the nuanced science behind what makes popcorn pop, from its botanical lineage and structure to the precise temperature and pressure thresholds that trigger its famous burst.

The Special Variety Called Zea Mays Everta

Popcorn comes from a particular type of maize, scientifically known as Zea mays everta. Unlike sweet corn or field corn, this variety has a thick outer hull (often called the pericarp) that’s crucial for popping. The hull traps moisture inside, allowing pressure to build.

Most grocery-store popcorn kernels feature a hard, glossy exterior. This robust casing is a hallmark of popcorn maize and ensures minimal water loss during storage. If the kernel’s hull is damaged or too dry, the essential moisture escapes, making the kernel unable to pop.

Many people assume any corn will pop if you apply enough heat. Yet, sweet corn or field corn won’t produce those fluffy flakes because they lack the right combination of hull strength, starch composition, and moisture ratio. This specialized genetic heritage is the baseline for everything that follows in popcorn science.

The Role of Moisture

Why Water Content Matters

A popcorn kernel’s moisture is the fuel for its pop. When heated, the water inside transitions from liquid to steam. As steam forms, it tries to expand about 1,600 times its original volume. This surge in volume inside the sealed hull is what builds the internal pressure that eventually rips the kernel open.

If the moisture content is too low (below around 13%), the steam pressure may never reach the critical threshold needed to rupture the hull. If it’s too high, the kernel can burst prematurely or become soggy. The ideal moisture range is carefully maintained by popcorn manufacturers who dry kernels to the right level before packaging.

Storing Kernels to Maintain Moisture

The best way to store popcorn kernels is in an airtight container at room temperature. Extended exposure to air can gradually dry them out. Some people swear by refrigerating kernels to protect their moisture content, although that can introduce condensation issues if not sealed properly.

Over time, kernels can lose water, leaving them less likely to pop. If you’ve had a bag of popcorn kernels in your pantry for a couple of years, you might notice a higher number of “old maids” (unpopped kernels). That’s often a sign they’ve lost the minimum moisture needed for a successful pop.

The Physics Behind the Pop

Temperature Threshold

Popcorn typically starts to pop around 180°C (356°F). At this temperature, water inside each kernel rapidly turns into steam. Starch granules within the kernel also begin to gelatinize, a process that makes them more flexible and ready to expand under pressure.

As the starch heats, it becomes a soft, gel-like material. This elasticity plays a big role in forming popcorn’s final shape once the hull fractures. Think of it like a balloon expanding under internal pressure—once the balloon bursts, all that pent-up energy is unleashed.

Pressure Build-Up

Under normal atmospheric conditions, water boils at 100°C (212°F). Inside the kernel, however, the hull traps the vapor, allowing the internal pressure to climb well above atmospheric levels. The steam can’t escape easily, so it pushes outward against the hull, intensifying the internal temperature and pressure together.

When the kernel finally ruptures, the pressure drops instantly. The softened, gelatinized starch rushes outward into the cooler surrounding air, forming that airy, lattice-like flake. The rapid cooling and expansion lock the starchy foam in place, giving you a crunchy, crispy snack.

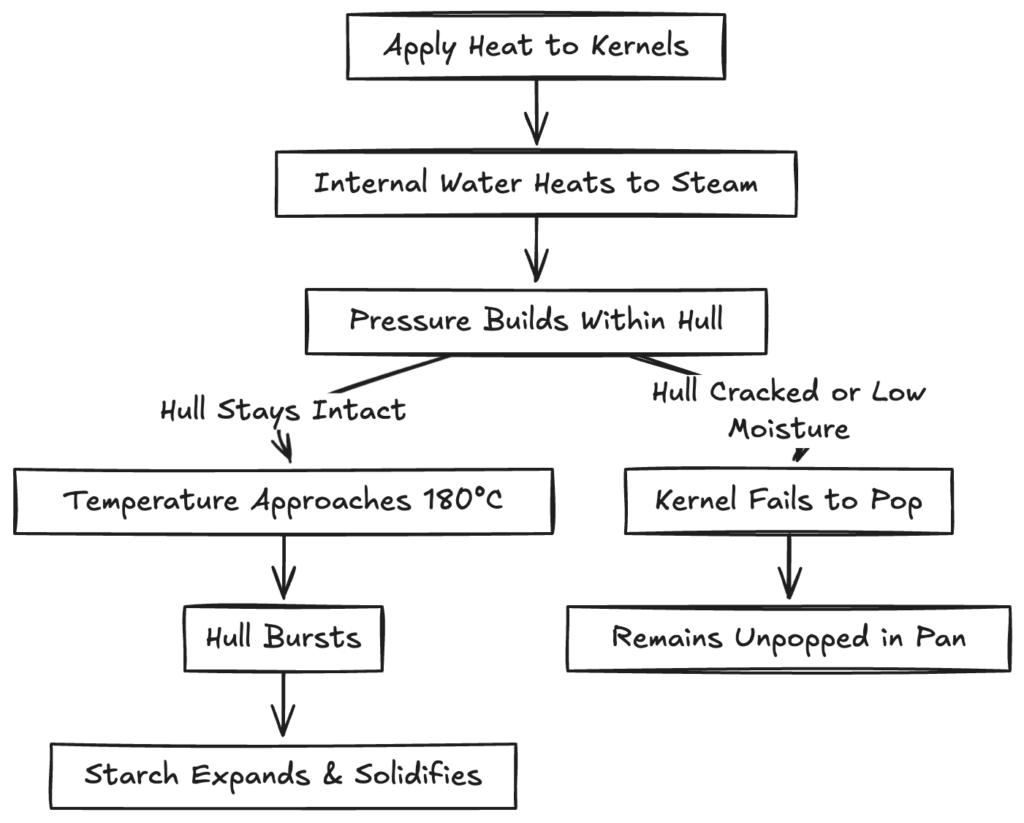

Diagram: Steam and Starch Unleashed

Below is a Mermaid diagram illustrating the branching process from initial heating to the final pop. Each stage depends on the kernel’s condition—like moisture level or hull integrity—to determine whether it pops or remains unpopped.

Diagram: The Popping Pathway

In an ideal scenario, kernels travel from heat application to a bursting hull, releasing gelatinized starch. If moisture is too low or the hull is compromised, they might skip straight to failure, explaining why some kernels never pop.

Inside the Kernel: The Starch Factor

Anatomy of a Kernel

Inside that tough hull lies primarily starch and protein, along with a small pocket of water. Starch granules are organized in a highly structured network. When these granules are heated in the presence of water, they absorb moisture and swell—much like pasta expanding in boiling water. This swelling contributes to the foam-like burst once the hull finally ruptures.

The starch’s type also matters. In popcorn maize, the amylase-to-amylopectin ratio differs from other corns. This unique composition helps ensure that the swollen starch forms a light, airy foam rather than a sticky paste. It’s one reason only specific corn varieties produce that classic fluffy texture.

Gelatinization and Foam Formation

Gelatinization is a process where starch granules absorb water and lose their crystalline structure, creating a gel. When you think of dough rising in an oven, or a sauce thickening on a stovetop, that same principle is at play. In popcorn, gelatinization happens under high pressure since the water can’t readily escape.

Once the hull bursts, everything happens in a split second. The hot steam blasts through, carrying the gelatinized starch outward. Exposed to cooler air, the starch quickly solidifies into the shape we recognize as popcorn. This rapid transition from gelatinized core to airy foam is key to popcorn’s trademark crunch.

Evolutionary Origins and Curiosities

Ancient Snack with Modern Appeal

Humans have been enjoying popped grains for thousands of years. Archaeologists have discovered remnants of puffed corn in sites across the Americas, suggesting that our ancestors recognized the value of this intriguing seed. Some cultures used it for religious ceremonies or decorative purposes, while others discovered its culinary potential.

The notion that a hard little kernel transforms into a fluffy snack might have seemed magical. In reality, it’s just water, heat, and starch dynamics in action. But it’s remarkable to consider how this process has remained mostly unchanged for centuries. Whether popped over an open fire or zapped in a microwave, the basic principle is the same.

Modern Breeding and Hybridization

Though the process is ancient, the popcorn you buy today is often the product of selective breeding. Scientists and farmers have worked together to improve kernel consistency, popping yield, and flavor. Different hybrids can produce butterfly-shaped or mushroom-shaped flakes, each with its own textural appeal.

“Butterfly” popcorn is the irregular, delicate shape with wings that branch out. “Mushroom” popcorn tends to form a more rounded, robust ball. Food industries often prefer mushroom popcorn for coatings like caramel, as the shape holds up better under tumbling and stirring.

Heat Sources and Their Effects

Stovetop Popping

When popcorn is heated in oil on a stovetop, each kernel is surrounded by a thin layer of hot oil. This improves heat transfer by evenly distributing the energy. The oil also helps coat the kernels, preventing them from scorching. Stovetop popping can be fast, efficient, and produce rich flavors—though it requires constant attention and frequent shaking of the pan.

If you’re wondering why some stovetop pops produce bigger, fluffier kernels, it often comes down to consistent heat. A heavy-bottomed pot can keep the temperature stable, allowing more kernels to reach the crucial popping threshold around the same time.

Air Poppers

Air poppers use a stream of hot air to heat kernels, requiring no added oil. This method is popular for health-conscious snackers because it avoids extra fat. The kernels bounce around in the popper’s chamber until they burst. Although air poppers can be a bit noisy, they reliably produce a large bowl of popcorn with minimal cleanup.

One challenge is preventing unpopped kernels from flying out before they reach the popping temperature. Some modern poppers use improved designs to funnel unpopped kernels back toward the heat stream. The result is a more thorough and efficient pop rate.

Microwave Popcorn

Microwave popcorn uses bags lined with a thin layer of metalized film that converts microwave energy into heat. This heat focuses on the kernels, speeding up the popping process. Some microwave popcorn varieties also include oils, flavorings, and seasoning packs sealed into the bag.

One quirk is that microwave ovens distribute energy unevenly, sometimes leaving “hot spots” or “cold spots.” That’s why you might get a mix of burnt pieces and unpopped kernels. Additionally, removing the bag too early halts the popping process, while leaving it in too long risks scorching. The sweet spot usually involves listening for the popping rate to slow to about one pop every second or two.

The Pop Sound: A Mini Explosion

Why Is It So Loud?

That characteristic popping sound is basically a mini explosion of steam. As the hull cracks, the sudden release of high-pressure vapor into lower-pressure air creates a shock wave. Most popcorn pops register somewhere around 90 decibels, though it can vary depending on how close you are to the kernel.

You can think of it like a small firecracker where the hull is the casing and steam is the explosive force. It happens on a much smaller scale, of course, but the physics is similar. Some studies suggest the pop can momentarily exceed 100 decibels if measured right near the kernel.

Speed of Expansion

The speed at which the starch foam expands can be over 15 meters (50 feet) per second, albeit momentarily. In slow-motion footage, you can see the kernel literally flip inside out in a fraction of a second. This rapid motion is what gives popcorn its distinct shape and occasionally launches it several centimeters above the pan.

The final flake is mostly air by volume, with a light, porous structure that makes it so crunchy. It’s almost as if each kernel becomes a tiny piece of expanded foam. Much of the water content quickly evaporates, leaving behind the crisp, hollow husk that characterizes popped corn.

Myth-Busting Popcorn Lore

“Myth: Any Corn Can Pop”

A common misconception is that all corn will pop if heated sufficiently. This simply isn’t true. Only certain varieties have the thick hull and starch composition needed for a successful pop. Field corn, flint corn, or sweet corn usually scorches or ruptures partially without forming the fluffy flakes we associate with popcorn.

Popcorn breeders specifically cultivate kernels with the right moisture retention and pericarp strength. If you pick random corn off the cob from a typical farm, it’s highly unlikely to yield proper popcorn results.

“Myth: You Should Store Popcorn in the Freezer”

While some recommend storing popcorn in the freezer to maintain moisture content, this can cause condensation when kernels are removed and warmed to room temperature. That moisture on the outside can create soggy conditions and encourage mold or staleness if not managed carefully.

A better approach is to store kernels in a cool, dry pantry, sealed in an airtight container. Freezing won’t necessarily harm the kernels if done in a completely moisture-proof bag, but it doesn’t offer a noticeable advantage over room temperature for most household scenarios.

“Myth: More Oil Always Means Bigger Pops”

You don’t need a lot of oil for massive, fluffy kernels. In fact, too much oil can overheat the exterior of the kernel while leaving the inside under-heated. A thin coating helps transfer heat uniformly, but drowning kernels in oil isn’t the key to a better pop. The best stovetop recipes often call for a modest tablespoon or two of oil for every half-cup of kernels.

Comparing Kernel Varieties

Butterfly vs. Mushroom Popcorn

“Butterfly” kernels produce the flake-like pieces many movie theaters favor. These irregular shapes create lots of surfaces for seasoning to cling to. On the other hand, “mushroom” kernels pop into more spherical shapes and hold up better under heavy coatings like caramel or chocolate.

Neither variety is inherently superior; it depends on personal preference and intended use. If you love lighter, crispier popcorn sprinkled with salt, butterfly might be your go-to. If you enjoy thick coatings or want to minimize breakage, mushroom popcorn is the better choice.

Colored Popcorn Varieties

You might spot red, blue, or purple popcorn at specialty shops. These colors usually refer to the kernel itself rather than the popped flake, which tends to be off-white. Some enthusiasts claim subtle flavor differences, with red popcorn sometimes described as “nutty” or “slightly sweet.” While these distinctions can be subtle, many people enjoy the novelty of cooking with colored kernels.

Whether you’re using standard yellow, white, or a rare variety, the science of popping remains the same—achieving the right heat and moisture balance to transform a tiny seed into a crunchy snack.

Health and Nutritional Considerations

A Whole Grain Option

Popcorn is a whole grain, meaning it includes all parts of the grain: germ, endosperm, and bran. This makes it relatively high in fiber compared to many other snack foods. Plain, air-popped popcorn is naturally low in fat and sugar, making it a popular choice for those seeking a healthier snack.

However, toppings can quickly change the nutritional profile. Adding butter, oil, cheese flavorings, or caramel can drive up calories and sodium. The beauty of popcorn is its versatility: You can enjoy it plain, add a sprinkle of herbs, or indulge in decadent toppings when the mood strikes.

Microwave Bags and Additives

Some microwave popcorn products include artificial flavorings or chemicals in the lining of the bag. In recent years, many manufacturers have moved away from problematic additives, but it’s still good practice to read ingredient labels. If you prefer full control over what goes into your popcorn, many brands now offer bags with minimal additives, or you can pop kernels in a paper bag yourself.

Troubleshooting and Tips

Why Do Some Kernels Stay Unpopped?

If you notice too many unpopped kernels, a few factors could be at play:

- Low moisture content due to poor storage or age

- Uneven heating that fails to bring all kernels to 180°C (356°F)

- Damaged hulls that let steam escape prematurely

Reviving slightly dried kernels by sprinkling a small amount of water and sealing them for a day can sometimes boost their pop rate, but there’s no guaranteed fix for every unpopped kernel. Sometimes, the hull might simply be compromised.

Preventing Burnt Popcorn

Burning often occurs when kernels remain in direct contact with a very hot surface without agitation. If you’re cooking on the stovetop, keep the kernels moving. In an air popper or microwave, remove the popcorn when the popping slows. Don’t wait for every last kernel to pop, as the few stragglers can overcook the rest.

It’s a balancing act: You want maximum popped yield without singeing. Listening for the “one pop per second” rule is a tried-and-true method. As soon as you hear more than a few seconds gap between pops, it’s time to turn off the heat or remove the bag from the microwave.

Beyond the Basics: Fun Experiments

Soaking Kernels for a Bigger Pop?

Some people experiment with soaking kernels in water for a few hours to increase moisture content. The theory is that extra moisture leads to increased pressure and thus bigger pops. Results are mixed. While soaking can rejuvenate slightly dry kernels, soaking too long might cause the hull to crack or lead to uneven heating. If you try it, pat the kernels dry before popping to avoid oil splatters or steam burns.

Adding Salt Before or After?

Have you ever noticed that popcorn salt is often extra-fine or powdery? That’s because smaller particles adhere better to the popped flake. Many chefs prefer salting after popping to ensure the salt sticks and doesn’t scorch. However, some like to dissolve salt in oil first, effectively creating a brine that coats the kernels. Both methods work, but watch out for burning if you add salt too early in a hot pan.

Cultural and Historical Perspectives

Mesoamerican Roots

Corn, or maize, originated in Mesoamerica (modern-day Mexico and Central America). Early varieties of popcorn likely existed well before written history. Evidence suggests pre-Columbian cultures popped corn in clay pots or by placing kernels directly on heated stones. Some even used the popped kernels in headdresses and ceremonial garlands, recognizing its aesthetic and cultural value.

The process eventually spread north and south across the Americas, where indigenous tribes found myriad uses for popped corn. In many traditions, it served not just as food but also as a symbolic offering in rituals. When European explorers encountered this phenomenon, they were intrigued by the popping transformation of maize.

Popcorn at the Movies

Popcorn’s status as a beloved movie snack took off in the early 20th century. Street vendors would set up outside theaters, offering patrons a cheap, tasty treat. Movie houses initially resisted, seeing popcorn as messy or too casual. But when profits soared, popcorn quickly became a staple inside the lobby. During World War II, sugar rationing made candy scarce, further cementing popcorn’s popularity as the go-to cinema snack.

Today, it’s nearly impossible to imagine going to a movie theater without the smell of freshly popped corn filling the air. That nostalgic aroma is inextricably linked to the silver-screen experience, continuing a tradition that’s over a century old.

The Joy of Seasonings and Recipes

Savory Twists

Popcorn’s neutral flavor is a blank canvas for all sorts of seasonings. Classic salted and buttered popcorn remains a favorite, but there’s no limit to creativity:

- Herb-Infused: Rosemary, thyme, or oregano

- Cheesy: Nutritional yeast (for a vegan twist) or powdered cheddar

- Spicy: Cayenne pepper, chili powder, or paprika

You can customize the intensity by layering flavors. Toss your popcorn with a bit of melted butter or oil to help spices adhere. Add small amounts of salt or powdered seasoning, taste, and repeat until you reach the perfect balance.

Sweet Indulgences

For a dessert-like experience, caramel corn is a classic. Hot caramel drizzled over freshly popped kernels cools into a shiny, crunchy coating. Other sweet ideas include chocolate drizzle, marshmallow melt, or a dusting of cinnamon and sugar.

When making candy-coated popcorn, be mindful of high sugar temperatures. It’s easy to burn the sugar—and your fingers—if you’re not careful. Silicone spatulas or heat-resistant gloves can help you handle the hot mixture safely.

FAQ Section

Does adding oil help my popcorn pop better?

A thin layer of oil improves heat conduction and keeps kernels from scorching. While it can help yield more even popping, too much oil can lead to uneven heating and excessive calories. Moderation is key.

What causes the “pop” sound?

The pop occurs when the hull bursts and hot steam rapidly escapes into cooler air. This sudden drop in pressure produces an audible mini explosion.

Why do some kernels pop only partially?

Partially popped kernels often suffer from lower moisture content or minor hull damage, preventing them from reaching the full pressure needed to expand completely.

Is air-popped popcorn healthier than stovetop or microwave popcorn?

Air-popped popcorn uses no added oil, making it lower in fat and calories. Stovetop and microwave versions can be equally healthy if you limit added fats and choose low-sodium seasonings.

Can I pop popcorn without special equipment?

Absolutely. You can pop kernels in a covered pot on the stovetop or even in a simple paper bag in the microwave. Just be sure to watch the heat and listen for the popping rhythm.

How do I minimize unpopped kernels?

Ensure your kernels are fresh and have the right moisture content. Store them in a sealed container away from excess humidity or dryness. Also, apply even, sufficient heat so each kernel can reach popping temperature.

Is there a difference between white and yellow kernels?

White kernels tend to produce smaller, more tender flakes, while yellow kernels often pop into larger, sturdier pieces. Taste is quite similar, though some prefer one texture over the other.

Read more

- On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee

Amazon Link - Popped Culture: A Social History of Popcorn by Andrew F. Smith

Amazon Link - Popcorn: A Pop-Up Book by Patrick Evans-Hylton

Amazon Link - Encyclopedia of Popcorn by Bridget Bufford

Amazon Link - Scientific American – Search “Popcorn Science”

Official Link

Popcorn’s legendary snap, crackle, and crunch has captivated humankind for centuries. Whether you favor air-popped purism or rich buttery indulgence, understanding the science behind what makes popcorn pop can add a deeper appreciation to every handful. The next time you fire up your popper, think of the microscopic drama unfolding inside each kernel: water boiling, pressure climbing, starch exploding—ending in that airy bite we know and love.