TL;DR: Inside a black hole lies a region of extraordinarily warped spacetime where matter collapses into a singularity, and our current physics can’t fully describe what truly happens beyond its event horizon.

Introduction

Imagine an object so dense and massive that nothing, not even light, can escape its gravitational grip. This is a black hole, a cosmic enigma so powerful that it bends the very fabric of space and time around it. While we now have images of a black hole’s “shadow,” captured by projects like the Event Horizon Telescope, we still cannot see directly inside. From the outside, black holes look like dark voids. But inside, the laws of physics are pushed to their breaking point. What exactly is in there?

As we embark on a journey into the heart of these cosmic titans, we find ourselves confronting deep questions about matter, energy, and spacetime. The truth is that current theories, including Einstein’s General Relativity and quantum mechanics, struggle to fully describe the realm beyond a black hole’s event horizon. Some hints come from theoretical modeling and mathematical exploration. Others emerge from the study of gravitational waves, high-energy astrophysics, and cutting-edge computer simulations. This article aims to pull together these threads into a comprehensive, accessible narrative—one that equips curious minds with the best understanding modern science can offer about what might lie inside a black hole.

Historical Background: How We Came to Know Black Holes

The idea of an object so dense that light can’t escape has roots dating back to the late 18th century. John Michell and Pierre-Simon Laplace speculated about “dark stars” that had gravity strong enough to trap light. However, it wasn’t until Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (1915) that a rigorous mathematical framework for such objects became possible.

- Karl Schwarzschild (1916): Shortly after Einstein published his field equations, Schwarzschild found a solution describing a static, spherically symmetric mass. This solution hinted at a boundary—now known as the event horizon—beyond which escape velocity exceeded the speed of light. For decades, this was considered a mathematical curiosity rather than a physical object.

- Oppenheimer and Snyder (1939): In a landmark paper, these physicists showed that a sufficiently massive star, after exhausting its nuclear fuel, could collapse under its own gravity to form what we now call a black hole. Their work demonstrated that black holes were not just theoretical constructs but likely real astrophysical entities.

- Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar: His work on white dwarf stars and stellar collapse established the mass limit (the Chandrasekhar limit) beyond which no stable white dwarf could exist, pushing theoretical physics closer to the inevitability of black holes.

- John Wheeler (1960s): Wheeler coined the term “black hole” and helped shape the modern concept in the public and scientific imagination. By the 1970s, black holes had moved firmly into the realm of mainstream astrophysics.

- Modern Era: With the detection of gravitational waves by LIGO in 2015, which confirmed black hole mergers, and the imaging of the black hole in M87 by the Event Horizon Telescope in 2019, black holes are now directly confirmed astrophysical objects. But these triumphs have only deepened the mystery of what lies inside.

(See NASA’s Black Hole Primer and publications in Nature for more historical details.)

Defining Black Holes: Key Terms and Concepts

Before we dive inside a black hole, let’s outline the key concepts needed to understand its structure.

- Event Horizon:

The boundary around a black hole from which no light can escape. Crossing this horizon is a one-way trip inward, as the curvature of spacetime turns all paths forward in time toward the central singularity.

(Wikipedia: Event Horizon) - Singularity:

A point (or region) where density and gravitational curvature become infinite in classical General Relativity. Traditional equations break down, and known physics no longer applies.

(Wikipedia: Gravitational Singularity) - Spacetime Curvature:

According to Einstein, massive objects warp the geometry of spacetime. In a black hole, curvature is so extreme that it essentially “closes off” the interior from the rest of the universe. - Schwarzschild Radius:

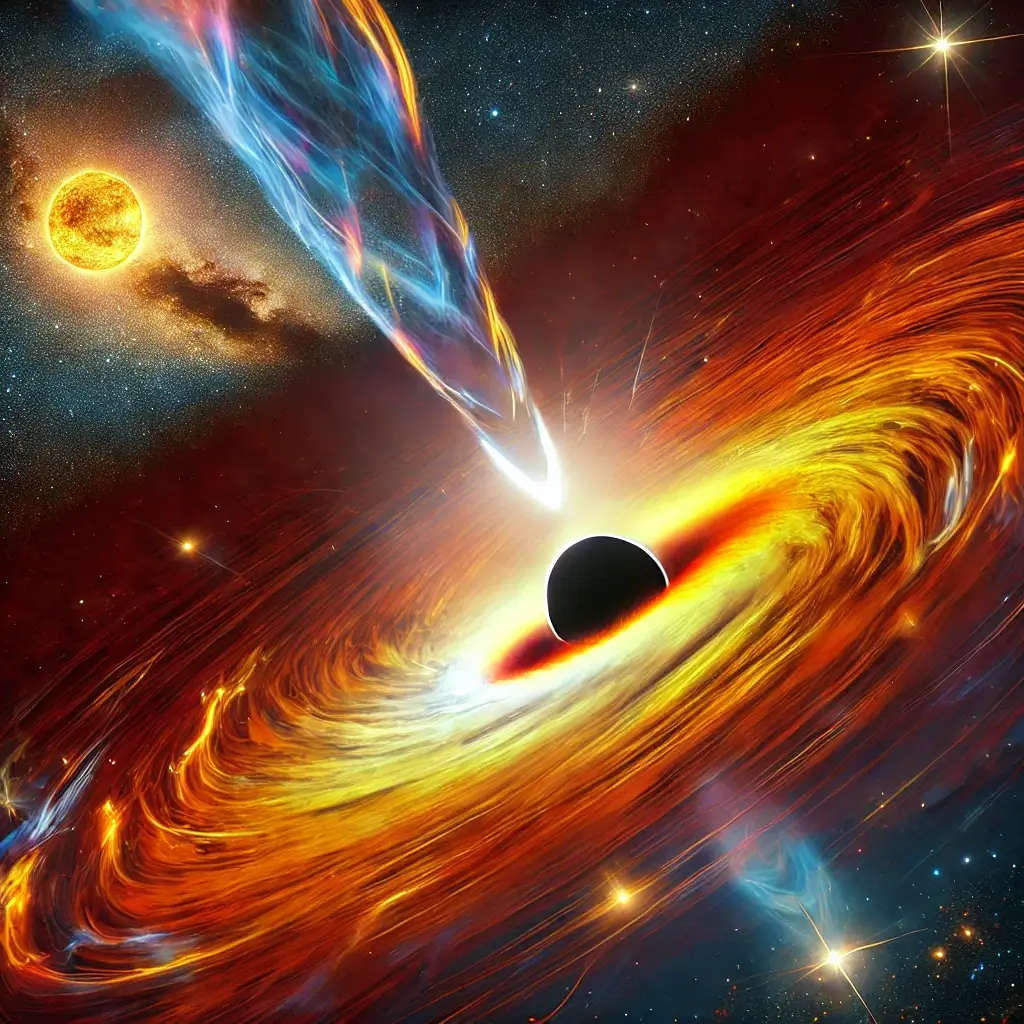

The radius at which the escape velocity equals the speed of light. Any mass compressed within its Schwarzschild radius becomes a black hole. - Accretion Disk:

Although not “inside” the black hole, the surrounding hot, glowing disk of infalling matter often signals a black hole’s presence. While interesting, the accretion disk lies outside the event horizon.

Understanding these terms provides the necessary toolkit to explore what might be going on inside a black hole’s mysterious interior.

What’s Inside a Black Hole? The Event Horizon and Beyond

The phrase “inside a black hole” is somewhat problematic because the structure of spacetime inside is not just a simple hollow sphere. Once you cross the event horizon, the geometry of spacetime becomes so extreme that the radial coordinate (the direction toward the center) starts to behave like time. In other words, after passing the event horizon, falling toward the singularity is as inevitable as moving forward in time.

Key Insight:

Inside the event horizon, all possible paths lead you closer to the singularity. You cannot stand still or turn around. No matter how powerful your rocket, you can’t escape. Just as you can’t avoid moving forward in time, inside a black hole, you can’t avoid moving inward. This radical rearrangement of what it means to move through space results from the intense gravitational field.

From the outside, one might imagine a solid object at the center of a black hole, but that’s not quite right. According to classical General Relativity, matter collapses into a zero-dimensional point of infinite density: the singularity. But this is where theory hits a wall. Infinite density and zero volume don’t align well with the laws of physics we know and trust—quantum effects must play a role.

(For more theoretical treatments, see discussions in ScienceDirect and research from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.)

The Singularity: Where Our Understanding Breaks Down

The singularity is often portrayed as the “heart” of a black hole. It’s where, theoretically, all the mass of the collapsed star (or whatever formed the black hole) is concentrated into a single point. The gravitational field here is predicted to become infinite, and the known laws of physics (General Relativity, quantum field theory, and the Standard Model of particle physics) cannot handle these infinities.

Why the Breakdown?

Einstein’s equations of General Relativity are classical—they don’t incorporate the uncertainty and quantum fluctuations that govern the microscopic world. Near a singularity, these quantum effects undoubtedly matter. We need a theory of quantum gravity, something that merges quantum mechanics and General Relativity, to describe what truly happens inside.

Possibilities at the Singularity:

- Quantum Foam or Planck-Scale Structure:

Some theories suggest that at very small scales (the Planck length, about 10−3510^{-35} meters), spacetime might become foamy or granular. If that’s the case, the notion of a singularity as a point might be replaced by a highly complex quantum state of space and time. - Black Hole Cores as Exotic States of Matter:

Theorists have speculated about hypothetical objects like “gravastars” or “fuzzballs,” which may replace the singularity with a more benign quantum object.

(Fuzzball Theory) - Avoiding the Singularity:

In some alternative theories of gravity, singularities do not form at all. Instead, exotic pressure or modified spacetime geometry could halt the collapse at a finite density.

Without direct observational evidence or a working quantum gravity theory, the singularity remains a paradoxical placeholder—an unanswered question at the boundary of our knowledge.

Spacetime Curvature: How Gravity Warps Reality

Black holes are essentially regions of spacetime so curved that the geometry itself is radically altered. Gravity, as described by General Relativity, is not a force pulling objects together; it’s the curvature of spacetime dictating how objects move.

Visualizing Curvature:

- Rubber Sheet Analogy:

Imagine a stretched rubber sheet representing space. Placing a heavy ball in the center causes the sheet to dip. Another smaller ball placed nearby rolls toward the heavier one. While this analogy is useful, a black hole’s curvature is more extreme. The “rubber sheet” analogy breaks down because in three-dimensional space (and one dimension of time), the curvature is not just a dip—it’s more like a funnel with no bottom. - Inside the Horizon:

The curvature inside the event horizon is not just a steep well; it’s so steep that all paths, even those you might think of as “upwards,” lead further inwards. There is no stable orbit, no stopping point. - Tidal Forces:

The intense gravitational gradients inside a black hole mean that different parts of an object are pulled differently. Near the singularity, tidal forces can become strong enough to stretch and squeeze objects into thin strands—an often-cited phenomenon called “spaghettification.” These tidal forces are a manifestation of extreme spacetime curvature.

(NASA’s explanation of gravitational waves and spacetime curvature provides insight into how gravitational fields influence the fabric of reality.)

Matter and Energy Within the Event Horizon

When something falls into a black hole—be it a star, a cloud of gas, or the unfortunate astronaut from a sci-fi scenario—it passes through the event horizon and continues inward. But what happens to it next?

- Compression and Heating:

As matter falls in, gravitational energy converts into heat and other forms of energy. Before crossing the event horizon, matter might spiral in through an accretion disk, heating up and emitting X-rays that we can observe. Once across the horizon, that matter continues to compress as it moves toward the singularity. - No Known Stable Form of Matter:

Ordinary matter cannot remain ordinary under these conditions. The atomic structure dissolves under immense pressure; even protons and neutrons may not survive in their familiar form. It’s possible that inside, matter becomes an unknown state—quarks, leptons, or something even more exotic—squeezed into unimaginable densities. - Loss of Identity:

From an external perspective, any detailed information about what fell in seems lost. Quantum mechanically, there’s tension here: information is a fundamental part of physics, and its destruction is problematic. This leads to the famous “black hole information paradox,” suggesting our understanding is incomplete.

(For further reading, see discussions in Nature Physics and Physics World about the states of matter in extreme environments.)

Falling In: What Would You Experience Approaching a Black Hole?

While it’s impossible to survive such a journey, a thought experiment can be enlightening. Suppose you, as a brave (or doomed) astronaut, approach a black hole:

- From Far Away:

Initially, you might not notice much. As you get closer, gravitational effects become more pronounced. Light from distant stars appears distorted as it bends around the black hole. - Closer to the Event Horizon:

Time dilation sets in—an observer watching you from far away would see your clock slow down as you near the horizon. To the distant observer, you never quite cross the horizon; you appear to slow and dim, freezing in time. However, from your perspective, you cross the event horizon in finite time without noticing anything particular at that boundary (assuming a large black hole where tidal forces at the horizon are modest). - Inside the Horizon:

Once inside, the singularity lies in your future. You can’t avoid it. Tidal forces grow stronger. You might be stretched and torn apart (spaghettified). As you move inward, the known laws of physics offer no escape or relief. - At the Singularity (Hypothetically):

Here, you’d be crushed into an infinitesimal volume as predicted by classical theory. But since no one can survive or communicate what occurs, and our theories break down, this is pure speculation.

While this is just a thought experiment, it illustrates how differently physics behaves near and within a black hole.

(See NASA’s page on black hole travel thought experiments and references in popular science literature.)

Black Hole Types: Stellar, Supermassive, and More

The internal structure described so far applies to all black holes, but black holes come in different sizes and masses:

- Stellar-Mass Black Holes:

Formed by the collapse of massive stars, these have a few times the mass of our Sun. Their event horizons are relatively small, and tidal forces at the horizon are extreme. - Supermassive Black Holes:

Found at the centers of galaxies, including our own Milky Way, these contain millions to billions of solar masses. Their event horizons are much larger, and tidal forces at the horizon might be milder, allowing you to pass through without immediate destruction (though you’ll still meet your doom eventually).

(Wikipedia: Supermassive Black Hole) - Intermediate-Mass and Primordial Black Holes:

Theoretical categories that fill in the mass spectrum. Primordial black holes may have formed shortly after the Big Bang. Their interiors would be no less mysterious.

In all cases, the internal dynamics are governed by the same principles of General Relativity and the same unknowns near the singularity. The main difference is scale: supermassive black holes have gentler gradients at the horizon, giving you a less violent entry, but the end result is the same—no escape and a final collision with the singularity.

Quantum Considerations: Do We Need a Theory of Quantum Gravity?

Why does our understanding fail at the singularity? Because we lack a theory that seamlessly unites General Relativity (which deals with gravity and large-scale structures) and quantum mechanics (which rules the realm of the very small).

Quantum Gravity Theories:

- String Theory:

In some versions of string theory, black holes have no sharp singularities. Instead, the “fuzzball” concept suggests that the singularity is replaced by a tangle of strings and branes, removing the infinite density problem.

(Fuzzball concept – Wikipedia) - Loop Quantum Gravity:

Another candidate is loop quantum gravity, which posits that spacetime itself is quantized. Near the singularity, spacetime might “bounce,” avoiding infinite densities and replacing the singularity with something finite and computable.

(Loop Quantum Gravity – Wikipedia) - Holographic Principle and AdS/CFT Correspondence:

Some frameworks suggest the three-dimensional interior of a black hole can be described by a two-dimensional boundary theory—essentially, the information about what’s inside could be “encoded” on the horizon. This could help resolve paradoxes about what goes on inside.

(Holographic principle – Wikipedia)

None of these approaches has yet provided a definitive, experimentally verified picture of what’s inside. But they show that theoretical physics is actively searching for a quantum gravity theory that can handle black hole interiors.

Information Paradox and Holographic Principles

One of the biggest puzzles about black holes is the so-called “information paradox.” According to quantum mechanics, information about a system’s state should never be destroyed. But if you throw something into a black hole, the information about its internal arrangement seems lost from the universe’s perspective—at least once the black hole evaporates via Hawking radiation.

Key Points of the Information Paradox:

- Hawking Radiation:

Predicted by Stephen Hawking in 1974, black holes emit thermal radiation due to quantum effects near the horizon. Over immense timescales, a black hole can evaporate completely. If all it leaves is featureless radiation, what happened to the information that fell in? - Potential Resolutions:

The holographic principle suggests that the information is not lost but stored in some scrambled form on the horizon. As the black hole evaporates, this information might be released in a highly scrambled form. Quantum gravity theories attempt to preserve unitarity (the principle that information is never lost) by intricate mechanisms we don’t yet fully understand. - Implications for Interior Structure:

The information paradox implies that the interior structure of a black hole is linked to the state of its horizon. This connection may reshape our understanding of what’s “inside” a black hole, making it less of a mysterious volume and more of a manifestation of complex quantum states.

(For detailed discussions, see articles in Nature and research from institutes like Perimeter Institute.)

Observing the Unobservable: Indirect Clues and Gravitational Waves

We cannot directly see inside a black hole. No light escapes to carry us information. But indirect methods provide clues:

- Gravitational Waves:

When black holes merge, they send out ripples in spacetime called gravitational waves. By analyzing these waves, detected by LIGO and VIRGO, scientists infer properties like mass and spin. While this doesn’t show the interior directly, it constrains theories about what’s inside. - Accretion Disks and Jets:

Observing matter swirling around a black hole, we learn about the environment near the event horizon. High-energy emissions (X-rays, gamma rays) from these regions give hints about the black hole’s gravitational influence and the conditions at its boundary. - Imaging the Shadow:

The Event Horizon Telescope’s images of supermassive black holes show a “shadow” against a backdrop of glowing gas. The shape and size of this shadow match predictions from General Relativity, confirming the presence of an event horizon and thus something like what we call a black hole interior. - Future Telescopes and Missions:

Next-generation instruments might detect subtle signatures of quantum gravity effects near horizons. Although seeing inside remains impossible, improved data could hint at the correct theoretical description of the black hole’s interior.

(For more, consult ESA’s Gaia mission and current astrophysics surveys studying black holes.)

Cultural Significance and Philosophical Questions

Black holes have captured the public imagination like few other cosmic objects. They appear in science fiction as portals, gateways, or monsters. Their mysterious nature—something that can swallow entire stars and warp spacetime—strikes a chord in human curiosity.

Philosophical Aspects:

- Nature of Reality:

If black holes represent a breakdown in our current theories, what does that say about the completeness of human knowledge? They challenge us to think about the nature of reality and the limits of scientific understanding. - Time and Causality:

Inside a black hole, the concepts of time and space get jumbled. Philosophers and physicists debate what this means for free will, determinism, and the flow of time. - Existential Awe:

The very idea that our universe contains objects that defy comprehension can be both humbling and inspiring. Black holes remind us of the vastness and strangeness of the cosmos.

From art and literature to movies like “Interstellar” (consulted with physicist Kip Thorne), black holes are woven into cultural narratives about mystery, danger, and the unknown.

Interdisciplinary Connections: Cosmology, Particle Physics, and More

Black holes are not an isolated phenomenon in astrophysics. They connect to multiple scientific fields:

- Cosmology:

Some theories suggest the universe might have been born from conditions analogous to a black hole singularity. Understanding singularities may inform our understanding of the Big Bang.

(Wikipedia: Big Bang) - Particle Physics:

The extreme energy densities inside a black hole may mirror conditions in particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Although we cannot replicate black hole interiors, high-energy collisions can offer insight into states of matter at extreme densities. - Holography and Information Theory:

Black hole research has stimulated entire branches of theoretical physics focused on information theory, entropy, and the relationship between gravity and quantum fields. - Quantum Computing and Simulations:

Some researchers use quantum computing simulations to model aspects of black hole behavior. Insights from black holes might inform quantum algorithms or encryption theories, as information and its transformations are central themes in black hole physics.

Common Misconceptions and Myth-Busting

With black holes being a popular subject, misconceptions abound. Let’s clarify a few:

- Myth: Black Holes Are “Cosmic Vacuum Cleaners” Sucking in Everything:

Reality: Black holes are just massive objects. They don’t “suck” more than any other body of the same mass would. If the Sun were replaced by a black hole of the same mass, Earth’s orbit wouldn’t change.

(NASA Black Hole Myths) - Myth: Inside a Black Hole Is a Hole to Another Universe:

Reality: While some speculative theories (like wormholes) suggest black holes could be gateways to other universes, there’s no evidence for this. Most physicists consider it extremely unlikely. - Myth: Black Holes Last Forever:

Reality: Due to Hawking radiation, black holes slowly lose mass and can eventually evaporate over immense timescales, though supermassive black holes last unimaginably long periods. - Myth: We Know Exactly What’s Inside:

Reality: We don’t. The singularity marks a breakdown of known physics. The internal structure remains a mystery.

Clearing up these misunderstandings helps sharpen the real intrigue and complexity of black holes.

Applications and Broader Implications: Understanding the Universe

Why does understanding the inside of a black hole matter?

- Fundamental Physics:

Black holes are natural laboratories for testing our theories at their limits. Insights gained here could lead to breakthroughs in unifying gravity with quantum mechanics. - Cosmic Evolution:

Black holes influence galaxy formation and evolution. Understanding their properties and growth can help us understand how galaxies form, evolve, and regulate star formation. - Astrobiology:

While not directly related to life, understanding extreme environments expands our sense of what the universe can do. It indirectly shapes how we think about exotic conditions, even those necessary for life in extreme places. - Technological Spin-Offs:

The mathematical and computational techniques developed to study black holes often find applications in other fields, including cryptography, materials science, and artificial intelligence research.

Knowledge about what might lie inside a black hole is a piece of a larger puzzle—one that aims to provide a complete picture of how our universe works from the smallest scales of quantum particles to the largest structures of galaxy clusters.

Conclusion: The Frontier of Knowledge

As we’ve seen, the question “What’s inside a black hole?” leads us into the deepest mysteries of modern physics. The event horizon forms a one-way boundary beyond which our familiar laws break down, pushing matter into a state that defies classical description. General Relativity predicts a singularity of infinite density, but this “infinity” is a red flag for incompleteness. We strongly suspect that quantum gravity—the next big leap in theoretical physics—will offer a more coherent picture, possibly revealing that singularities are replaced by complex quantum structures or new states of spacetime.

For now, we stand at the edge of a profound mystery. Advances in gravitational wave astronomy, black hole imaging, and theoretical physics may one day give us a clearer answer. Until then, black holes remain cosmic riddles that challenge our understanding of nature’s laws.

Have thoughts or questions about this cosmic enigma? Feel free to share your comments, pose new questions, and dive deeper. Your curiosity fuels the ongoing conversation and might even inspire the next generation of scientists to unlock the secrets hidden within these darkest corners of the universe.

Key Points

- Black holes feature an event horizon beyond which no light can escape.

- Inside, spacetime is severely curved, funneling all matter toward a central singularity.

- Classical physics predicts infinite density and a breakdown of known laws at the singularity.

- Quantum gravity is needed to properly describe the black hole interior.

- The black hole information paradox and holographic principles offer clues but no final answers yet.

- Observations of gravitational waves, accretion disks, and the black hole “shadow” inform our theories, but direct observation inside is impossible.

- Black holes drive interdisciplinary research across cosmology, particle physics, and quantum theory.

References

Authoritative Organizations and Educational Resources:

- NASA – Black Holes

- ESA – Black Holes

- Event Horizon Telescope

- LIGO – Gravitational Waves and Black Holes

Peer-Reviewed Journals and Scientific Databases:

- Hawking, S. W. (1974). Black hole explosions? Nature, 248, 30–31. Nature Link

- Bekenstein, J. D. (1973). Black Holes and Entropy. Physical Review D, 7(8), 2333–2346. ScienceDirect Link

- Penrose, R. (1965). Gravitational Collapse and Space-Time Singularities. Physical Review Letters, 14(3), 57–59. APS Link

Wikipedia for Background Concepts:

Recommended Books for Further Reading:

- Thorne, K. S. (1994). Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy. Amazon Link

- Wald, R. M. (1984). General Relativity. Amazon Link

- Hawking, S. (1988). A Brief History of Time. Amazon Link

These resources provide avenues for deeper exploration, helping you continue your quest to understand what’s inside a black hole and the profound implications for physics and our understanding of the universe.