TL;DR: Explosive substances store large amounts of chemical energy that can be released almost instantly, whereas inert materials either lack reactive bonds or break down so slowly that they pose no explosive danger.

The Chemistry Behind Explosives vs. Inert Substances

When we think of explosive materials, images of fireworks, dynamite, or rocket fuel may come to mind. Meanwhile, most substances we encounter—like table sugar, sand, or water—remain practically inert, refusing to combust or detonate under everyday conditions.

This disparity originates in chemical bonds, molecular structure, and how energy is stored and released. Explosives possess unstable bonds ready to break down quickly, releasing gas, heat, and pressure. Conversely, inert substances lack these reactive bonds or require extremely high energy to ignite, resulting in slow or negligible reactions.

What Makes a Substance Explosive?

To be explosive, a substance must meet three main criteria:

- Energy-Rich Structure: Contains chemical bonds with large amounts of stored potential energy.

- Instability: Can be triggered to break those bonds rapidly.

- Rapid Energy Release: Produces gases that expand violently, creating pressure waves (the “bang”).

Bond Instability and Activation Energy

Many explosive materials rely on nitrogen in their structure—like TNT (trinitrotoluene) or RDX. Nitrogen-based bonds can be both high in potential energy and relatively easy to break, making them prime candidates for explosions.

Activation energy is the minimum energy needed to start a chemical reaction. For explosives, a small input (like heat, shock, or friction) can surpass this threshold, unleashing the reaction.

Why Some Substances Are Inert

On the opposite end, inert substances are stable. Materials like helium gas, glass, or certain noble metals (e.g., gold) have either:

- Full electron shells (like noble gases), leaving them chemically uninterested in reacting.

- Strong, robust bonds that require immense energy to break.

- Structures that resist rapid decomposition (like silica in sand).

Even some everyday chemicals (like sugar) can release energy if burned, but they do so gradually under normal conditions, lacking the self-sustaining rapid chain reaction that defines an explosion.

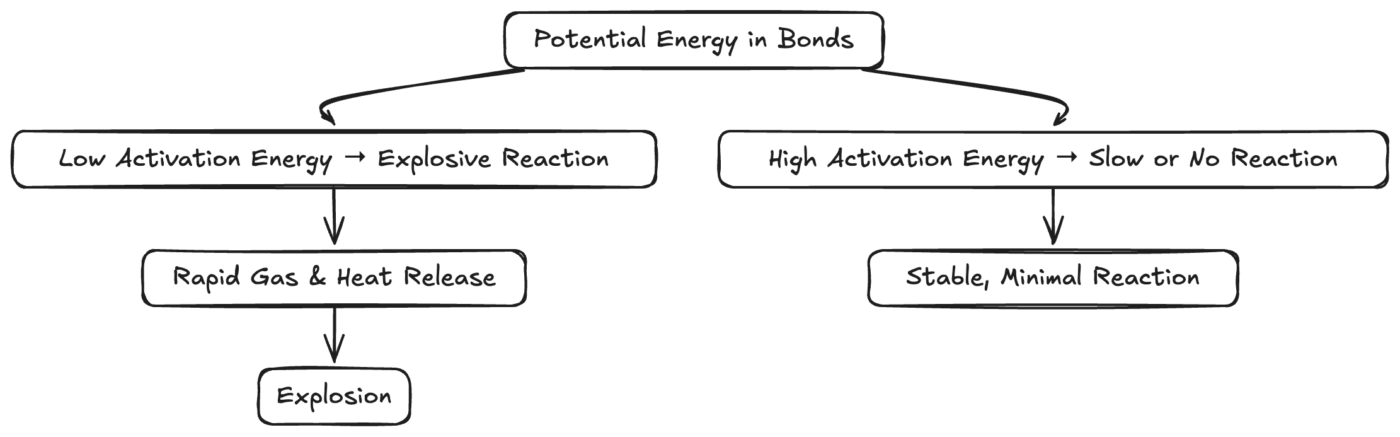

Diagram: Factors That Lead to Explosiveness vs. Inertness

Diagram: Shows how the activation energy and amount of stored energy can branch into violent explosions or stable inertness.

The Role of Oxygen and Other Oxidizers

Oxidizers supply the oxygen needed for rapid combustion. Many explosives (like black powder) pair a fuel with an oxidizer (e.g., potassium nitrate). When ignited, the oxygen is immediately available, speeding the combustion beyond typical burning.

In contrast, slow reactions rely on ambient oxygen from the air, limiting how fast the fuel burns. Think of a smoldering campfire. It’s the same fundamental chemistry as an explosion but unfolds at a snail’s pace compared to a bomb detonation.

Exothermic vs. Endothermic Reactions

Exothermic reactions release energy. For explosives, this release happens in microseconds, creating intense heat and shockwaves. Endothermic reactions, on the other hand, absorb energy. Substances that undergo endothermic processes don’t spontaneously blow up because they require continuous energy input to proceed.

In an explosive breakdown, chemical bonds reorganize into more stable products. The difference in energy levels is released as kinetic energy, heat, and pressure. This avalanche effect is what we see and hear as an explosion.

Stability and Energy Thresholds

Not all substances with high energy are explosive. For instance, gasoline is energy-rich but typically just burns with a flame. It needs specific conditions—like confinement and a proper fuel-air mixture—to explode. Even then, it’s more of a deflagration (rapid burning) than a high-order detonation.

High explosives (like PETN or dynamite) create supersonic shockwaves. Low explosives (like black powder) burn rapidly but subsonically, generating propulsive gas flow. The difference lies in how fast the reaction front travels through the material.

Reactive Groups: Nitrogen, Peroxides, and Beyond

Some of the most unstable compounds feature nitro groups (–NO₂). These groups store oxygen and nitrogen in a precarious arrangement. Organic peroxides also rank among the most hazardous, as their O–O bonds require minimal energy to break apart.

Common examples:

- TNT (Trinitrotoluene): Nitro groups attached to a toluene ring.

- RDX (Cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine): A cyclic arrangement of nitro groups and nitrogen.

- TATP (Triacetone Triperoxide): A peroxide-based explosive that’s highly sensitive and dangerous.

Inert Gases: The Epitome of Stability

At the opposite extreme, noble gases like helium, neon, or argon have complete electron shells, making them largely immune to typical chemical reactions. They don’t form unstable bonds easily, so there’s almost no potential for explosive decomposition.

Solid substances can also be nearly inert if their bonds are too strong or if breaking them doesn’t yield enough energy to fuel a chain reaction. Glass (silicon dioxide) has a tight lattice, so it just melts or fractures—it can’t spontaneously combust or explode.

The Chain Reaction Factor

A hallmark of an explosive event is a chain reaction. Once the initial bonds break, they set off adjacent molecules, generating a self-propagating wave of decomposition. That wave is the essence of an explosive reaction—it feeds itself until all available fuel reacts.

How Chain Reactions Differ for Inert Materials

In inert materials, even if you manage to break a few bonds, nothing “catches on” to sustain the reaction. The local bond rupture dissipates, and the system returns to stability. Without a domino effect, you don’t get a full-blown explosion.

Comparisons: Fireworks vs. Rusting Metal

Fireworks vividly illustrate controlled explosions. They contain mixtures of metals (for color) and oxidizers. The chemical reaction ignites rapidly, producing heat, light, and gas in mere seconds.

Rusting is also an oxidation reaction with iron and oxygen—just extremely slow. Over months or years, iron converts to iron oxide (rust). The process yields minimal immediate heat and no shockwave. Despite both being oxidation, the reaction rates differ by orders of magnitude.

The Importance of Activation Energy

If Earth were the size of a basketball, the difference between a stable substance and an explosive might be akin to having a very high fence around the basketball vs. no fence at all. Some chemicals are locked behind a tall fence (high activation energy), so only extreme conditions can spark a reaction. Explosives have a low or easily surmountable fence, so a tiny push triggers a huge transformation.

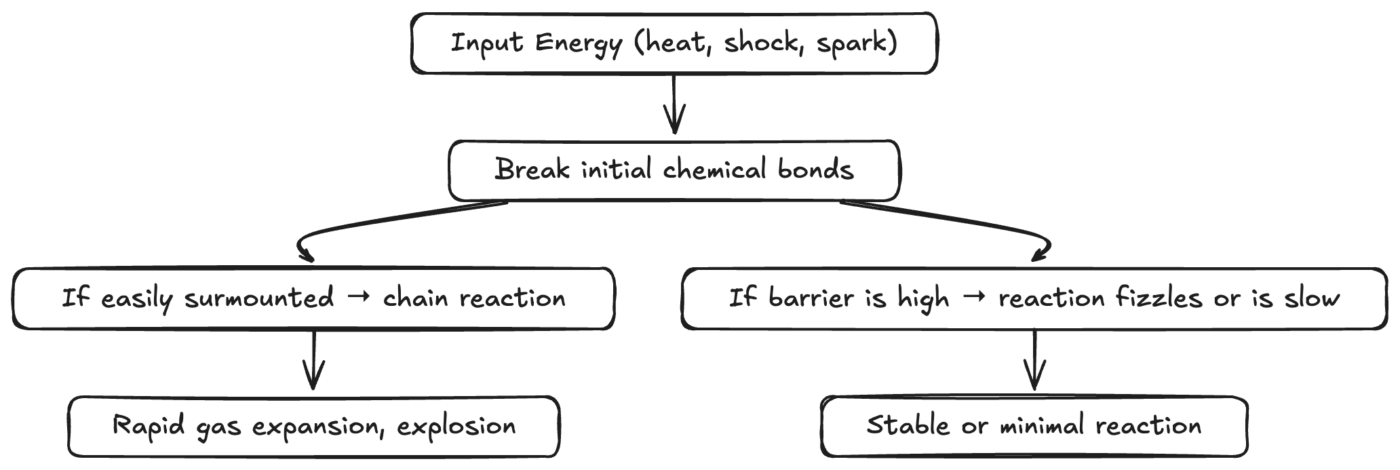

Diagram: Pathways to Explosive or Inert Reactions

Diagram: Shows how a small input of energy might lead to a self-sustaining reaction or fizzle out.

Myth-Busting Common Misconceptions

Myth: Anything that burns can explode

Reality: Burning is not automatically explosive. Substances like wood or cooking oil burn rather than detonate. Explosions need fast, runaway chemistry.

Myth: Explosives always require oxygen from air

Reality: Many high explosives carry their own oxidizing groups (like –NO₂), enabling them to detonate in oxygen-poor environments. That’s why underwater or space explosions are possible with the right chemicals.

Myth: An inert material can’t be made explosive

Reality: In bulk, certain materials might be inert. But if finely powdered and mixed with an oxidizer, they can become dangerously reactive. Dust explosions in grain silos illustrate how even “inert” food can blow up under the right conditions (fine particles + oxygen + spark).

The Role of Catalysts and Sensitizers

Sometimes a substance isn’t explosive on its own but becomes so when mixed with a catalyst or sensitizer. These additives lower the activation energy or help form highly reactive intermediate compounds.

Example: Ammonium nitrate is relatively stable but can become powerfully explosive if contaminated with fuel and heated. The Texas City disaster in 1947, involving an ammonium-nitrate-laden ship, highlights this risk—an unintended mixture led to a massive explosion.

Real-World Uses of Explosives

Explosives play critical roles in:

- Mining and Construction: Blasting rock efficiently.

- Space Exploration: Launch vehicles need controlled rocket propellants.

- Military and Defense: Conventional weapons.

- Fireworks and Entertainment: Visual spectacles.

Despite the negative association, controlled explosions can be beneficial when managed responsibly.

Real-World Uses of Inert Materials

Inert materials serve:

- Protective Environments: Argon or nitrogen atmospheres to protect reactive metals during welding.

- Storage: Helium in scientific instruments, preventing unwanted reactions.

- Containers: Glass or stainless steel for reactive chemicals, ensuring no side reactions occur.

Inertness is often prized when you need stability, longevity, or minimal reactivity.

Handling Explosive Substances

Because explosive compounds can be triggered by heat, friction, or impact, strict protocols govern their transport, storage, and use. Even small changes in packaging or temperature can be catastrophic if not carefully managed.

Stability can be improved by adding phlegmatizers—ingredients that reduce shock sensitivity. For instance, TNT is often mixed with wax or other stabilizers to lower the chance of accidental detonation.

FAQ Section

How do everyday items compare in terms of explosiveness?

Common household substances like baking soda or salt are inert under normal conditions. Even flour can become flammable if dispersed as a fine dust. Only specialized chemicals (e.g., nitroglycerin, black powder) are truly explosive in small quantities.

Are explosives always dangerous to handle?

Yes. By definition, they’re prone to releasing energy rapidly. However, many commercial explosives are formulated with stabilizers, requiring a detonator to set them off, reducing the chance of accidental ignition.

Why is water sometimes used to “disarm” explosives?

Water can absorb heat, cool the explosive, and sometimes separate reactants. High-pressure water jets can disrupt the explosive charge, preventing a chain reaction.

Could we make a noble gas explosive?

No. Noble gases resist forming bonds, so they can’t store the necessary energy for a chemical explosion. They might liquefy or freeze under extreme conditions, but they don’t chemically react in ways that produce rapid energy release.

Do biological processes ever mimic explosions?

Some examples exist: the bombardier beetle sprays hot, noxious chemicals in a rapid reaction, resembling a mini-explosion. Certain seed pods burst explosively to disperse seeds. But these processes are generally less intense than man-made explosives.

Conclusion: The Fine Line Between Boom and Bust

The difference between an explosive and an inert substance is all about chemical bonding and how easily that stored energy can be unleashed. By understanding bond stability, oxidation, and activation energy, scientists and engineers harness explosive forces for construction, space travel, and more—while also relying on inert materials for safe containers, protective atmospheres, and countless everyday uses.

Ultimately, the next time you strike a match or see fireworks, you’re witnessing a precarious balance of chemistry and energy—carefully controlled to create awe-inspiring displays or perform essential tasks without catastrophic release. It’s the delicate dance of molecules that determines whether something goes boom or remains quietly inert.

Read More

- The Chemistry of Explosives by Jacqueline Akhavan (Amazon)

- Explosives: History with a Bang by Alan Ward (Amazon)

- Inorganic Chemistry by Shriver & Atkins (Amazon)

- Royal Society of Chemistry – Explosives

- U.S. Bureau of Mines – Historical Explosives Research Archives

These references and resources provide deeper dives into what makes some substances explosive, why others remain unreactive, and how we apply these properties in both practical and spectacular ways.