TL;DR: Most of our brains before age two are busy laying down essential neural foundations, so those early experiences don’t get encoded into long-lasting, retrievable memories.

The Mysterious Gap in Our Memory

It’s easy to recall moments from our childhood, like a special birthday party at age five or a fun day at the park around age three. Yet when we try to peer back even further—say, 18 months or younger—our mental cinema draws a blank. This universal experience of forgetting early events often sparks curiosity and even frustration.

But there’s solid science behind why we have no reliable memories from infancy. Psychologists and neuroscientists call this phenomenon infantile amnesia, referring to the inability of adults (and older children) to retrieve episodic memories from infancy or early childhood. Our brains at that time are like construction sites with scaffolding everywhere. Structures critical for memory formation, especially in the hippocampus and surrounding regions, haven’t finished building. By the time these regions are ready for business, those early “recordings” are often gone.

Infant Brain Development and Memory

We tend to think of memory like a tape recorder, automatically capturing everything. But human memory is more like a carefully orchestrated process that requires multiple parts of the brain working in harmony. In early childhood, these parts are still forming fundamental connections.

Brain Maturation and Neural Pathways

The hippocampus, a key brain structure for memory, is under heavy construction in the first two years of life. Though present at birth, its intricate neural connections aren’t fully developed. These connections help convert experiences into long-term memories. Essentially, the hippocampus is the director of memory encoding, storage, and retrieval, but it needs a well-established network to do its job effectively.

Neurons, the brain’s nerve cells, extend branches called dendrites, forming synapses with other neurons. In infancy, these synapses grow in abundance, creating an environment rich in neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself. Around the ages of one to two, the brain is more focused on building essential life skills, like motor coordination and basic communication, than on cataloging explicit memories.

Synaptic Pruning and the Trimming of Connections

Around age two or three, the brain initiates a massive cleanup known as synaptic pruning, where it eliminates weaker, surplus connections. This is like decluttering a busy workshop—tossing out unused tools to make the workspace more efficient. The process helps sharpen the pathways we use more often, but it may also sacrifice some pathways that were holding early memories.

Synaptic pruning is beneficial in the long run. It streamlines the system, making learning faster and more effective. But it often means that whatever ephemeral connections encoded those infant experiences could be lost. When we later try to recall something from our infant days, we find little to no trace of it.

A Simplified Look at Memory Formation

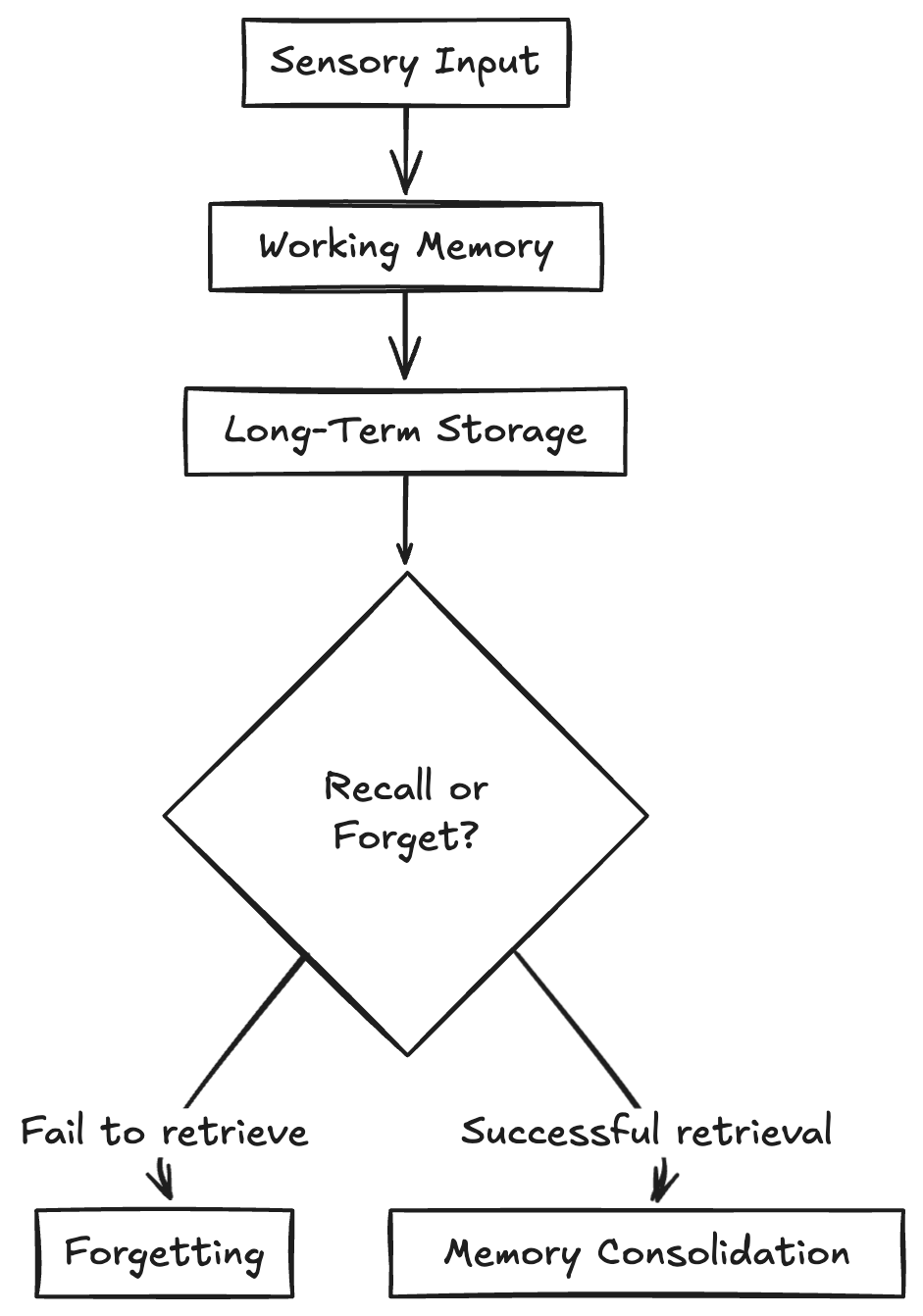

To visualize the path an experience takes from the moment it occurs to when we recall it later, consider this flowchart:

Diagram: The Basic Pathway to Memory Formation

Memories start as sensory input from our environment. These inputs, such as sights, sounds, or tactile sensations, get processed in working memory. With further reinforcement, they transfer to long-term storage, primarily in the hippocampus and other related areas. Later, our brain tries to recall these memories. If the retrieval process fails or the trace is weak, the experience might be forever forgotten. If it succeeds, the memory is consolidated, making it more stable for future retrieval.

In infants, the early pieces of this pathway function, but not at the level needed for long-lasting autobiographical memories. The system is too immature to effectively consolidate these experiences, so they vanish into oblivion as the brain reorganizes itself.

Language and Memory Encoding

An often-overlooked aspect is the role of language. Language provides labels and structures for our experiences, helping store and retrieve them. In infancy, language skills are minimal. We don’t have the vocabulary to label an event (“I was at the zoo, looking at giraffes, with my grandparents”), making it challenging to solidify the memory. Over time, as language develops, so does our ability to create more detailed autobiographical accounts.

The Crucial Link Between Language and Memory

We use words, stories, and narratives to give meaning to our experiences. When a toddler can say “big giraffe,” that simple phrase anchors a memory. In contrast, a six-month-old, while possibly experiencing wonder at a giraffe, lacks the verbal tools to encode that wonder in a retrievable form.

Many studies highlight that children develop stronger and more vivid autobiographical memories once they start talking fluently. It’s as if language acts like a scaffolding system, enabling the brain to categorize and store life events more efficiently. Before that, we rely on nonverbal memory systems, but those have limited retrieval capacity in later childhood or adulthood.

The Concept of Self in Memory Formation

Besides language, our sense of self or personal identity also factors into memory consolidation. Infants don’t possess a fully formed understanding of themselves as separate beings capable of reflecting on their own experiences. Without this sense of self, events don’t get placed into the mental timeline we use to track our life’s story.

Self-Awareness and Autobiographical Memories

Autobiographical memory is inherently tied to how we see ourselves. As we mature, we develop an internal narrator that weaves our experiences into a cohesive story: “I rode a bike for the first time when I was four.” For an infant, there is no such personal storyline. Experiences may be stored in fleeting forms, but they remain unlinked to a stable self-identity, reducing the chances we’ll recall them years later.

Perspectives from Psychology and Neuroscience

For decades, scientists and psychologists have tried to pinpoint the exact cause of infantile amnesia. Sigmund Freud once suggested that repressed desires and traumatic content from infancy block our memories, but modern research leans heavily on neurological development rather than psychoanalytic theory.

Contemporary scientists converge on a blend of factors: incomplete hippocampal structures, limited language, underdeveloped self-concept, and rapid neuroplastic changes that rewire a child’s brain during the critical first years. The synergy of these elements makes it nearly impossible to create stable, detailed recollections of infancy.

Real-World Analogies: Building a House

Imagine constructing a house. At first, you erect a rough framework without walls or doors. You might haul in materials—wood, cement, tools—and scatter them around the site. That’s like an infant’s brain, full of neurons and early connections but lacking the full architecture to protect and organize “memories.”

Over time, you place walls, install wiring, and hook up plumbing. You might discard leftover materials because the house no longer needs them. This is synaptic pruning. Eventually, you have a fully functional home with a stable structure. By the time the house is complete, many early items may have been thrown away, which parallels how early memories are lost amid the brain’s reorganization.

The Emotional Factor

You might wonder: what about extremely emotional events? Surely, those get stamped onto our brains, right? Even in older children and adults, strong emotional experiences have a better chance of being remembered. But in infancy, the brain’s emotional center (the amygdala) and the hippocampus must coordinate more effectively to preserve an event in detail. That coordination remains immature in very young infants.

While newborns show emotional reactions—crying from discomfort, smiling at a familiar face—the ability to store these emotional moments as long-term autobiographical memories is still a work in progress. So even strong emotions at that age might not pierce the protective layers of early forgetfulness.

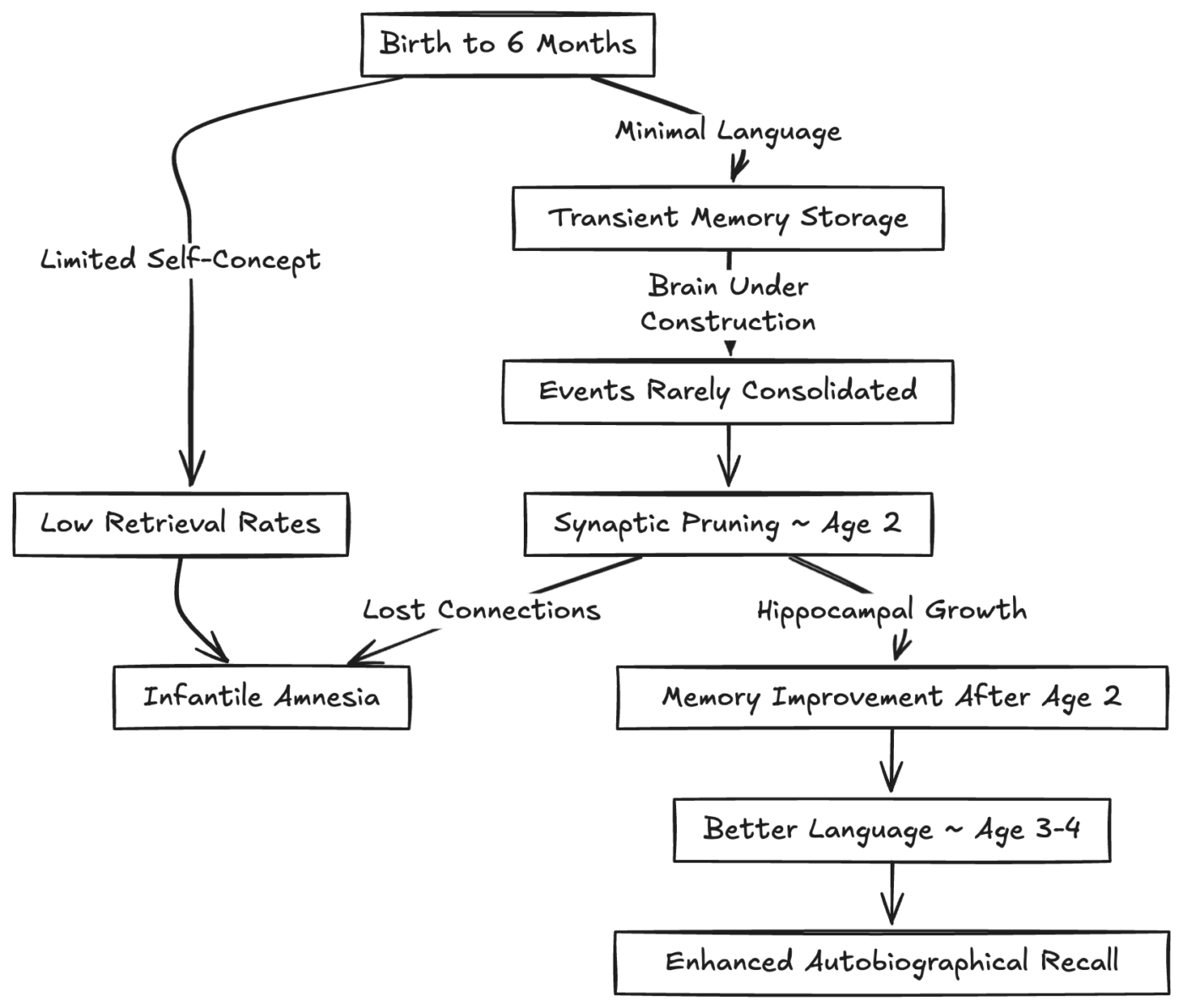

Diagram: Evolution of Memory Through the Early Years

Below is a mermaid diagram illustrating how memory capabilities evolve from birth to around four years old. Notice the branching for events and the likelihood of recall.

The diagram shows multiple paths: one set of paths leads to minimal memory encoding in infancy, resulting in infantile amnesia. Another path, symbolized by hippocampal growth and better language skills, significantly improves memory retrieval after age two or three.

Myth-Busting: “Babies Don’t Form Memories at All”

Myth: Infants can’t form memories, so there’s no point in reading to them, playing games, or offering stimulating experiences.

Reality: Babies do form memories—but these are mostly implicit or procedural memories, such as recognizing faces, learning to crawl or walk, and understanding cause and effect in a limited way. The fact that they can adapt and learn proves they register experiences. However, these early memories typically aren’t retrievable as conscious, verbal narratives in later life.

Engaging with babies is still immensely beneficial for their overall cognitive and emotional development. Even though they may not remember a reading session three years later, the act of reading helps strengthen neural networks that will support language and literacy later on.

Relatable Comparison: Vintage Film Reels vs. Digital Archives

Think of your earliest months as vintage film reels shot on a camera with poor focus. The film existed, but it was never converted to a stable digital format for easy viewing. Then, as your mental technology upgraded—similar to going from film to high-quality digital archiving—the old film reels became inaccessible.

In other words, those infant experiences happened, but the brain’s archival system had not yet moved from an “analog” method to a more “digital” storage method, rendering the earliest footage lost to time.

The Role of Caregivers and Environment

Parents and caregivers play a major role in shaping early experiences, even if the child won’t remember the events explicitly. Infants still benefit from nurturing, interactive environments—which support language acquisition, emotional security, and healthy brain growth.

Experiences like singing lullabies, offering varied toys, or simply talking to a baby all contribute to the child’s overall development. Over time, these building blocks help accelerate the shift from fleeting infant perceptions to lasting childhood memories.

Cultural Differences in Early Memory

Interestingly, cultural factors can also influence when our earliest memories solidify. Research shows that children who grow up in highly narrative-based cultures—where parents constantly recount events and ask the child about their day—tend to develop autobiographical memories at younger ages. In contrast, cultures that don’t emphasize talking about past experiences lead to slightly later recollections in childhood.

While the difference isn’t drastic—every child eventually develops personal memories—this finding underlines the interplay between environment, language, and memory formation.

FAQ

Why do some people claim to remember things from infancy?

Some adults insist they can recall lying in a crib or being fed in a high chair. Psychologists suggest these “memories” may be reconstructions pieced together from family stories, photographs, or vivid dreams. Over time, our brains integrate this information into a narrative that feels like a true memory, even though it might not be a direct recollection of the actual event.

Is there any way to recover those lost infant memories?

There is no scientifically validated method to fully recover true memories from infancy. Techniques like hypnosis or guided imagery can produce illusions of memory, but these are highly prone to fabrication and suggestion. Once the neural connections that stored those experiences are pruned or rewritten, the original content is generally gone for good.

Can trauma experienced in infancy be remembered later?

Severe or highly traumatic events in infancy can sometimes leave a strong emotional or behavioral imprint, even if the individual can’t consciously recall the details. In some cases, fragments might emerge, but it’s often implicit rather than explicit memory. Therapists and neuroscientists agree that while early trauma can shape emotional responses and stress-related behaviors, explicit recall of such events before age two is extremely rare and not entirely understood.

Does this phenomenon extend to other mammals?

Many mammals show a form of infantile amnesia. Rodent studies have demonstrated that infant mice and rats forget early experiences more quickly than older animals, due to ongoing brain development. This suggests infantile amnesia might be a widespread, adaptive process rather than a human-specific quirk.

Does language help prevent “amnesia” for events after age two?

Yes, the onset of language aids in forming more durable autobiographical memories. By labeling experiences (“We went to the beach,” “We saw fish”), toddlers can create anchors that help them recall events months or years later. Studies show that the richer a child’s vocabulary, the better they perform on memory tasks involving personal experiences.

Practical Tips for Parents

- Talk to Your Baby: Even if they can’t reply, hearing language from an early age promotes vocabulary growth and eventual memory formation.

- Use Photos and Stories: Recounting recent events and showing pictures soon afterward can help your toddler begin creating a personal narrative.

- Engage All Senses: Activities involving touch, smell, and taste can help form strong, multi-sensory memories, which might last longer than purely visual experiences.

- Be Repetitive: Infants learn through repetition. The more frequently a skill or piece of knowledge is reinforced, the likelier it becomes part of long-term memory later.

Future Research and Possibilities

Neuroscientists continue to explore the intricate dance between neural plasticity and memory consolidation. Advanced imaging techniques, like fMRI, shed light on how certain areas of a baby’s brain activate during learning tasks. These findings could help shape early childhood education, developmental psychology, and interventions for learning disabilities.

As we learn more about the molecular mechanisms of memory, we might discover ways to optimize mental development. For now, the consensus remains that infantile amnesia is a normal byproduct of our brain’s early expansion and reorganization.

Beyond Age Two: The Rise of Self-Knowledge

By age three or four, children begin forming the first stable pillars of autobiographical memory. They can tell you their favorite color, recall a simple vacation story, or identify a friend from preschool. While these recollections may still fade with time, a framework for permanent storage is finally in place.

The shift often correlates with improvements in linguistic skills and self-awareness. A child might start using pronouns like “I” or “me,” indicating a budding sense of personal identity. This new sense of self becomes the anchor for building a life story, step by step.

A Quick Recap in List Form

For those seeking a concise overview:

- Hippocampal Immaturity: Critical memory structures aren’t fully developed in infancy, limiting stable memory storage.

- Synaptic Pruning: The brain trims excess neural connections, potentially discarding early memory traces.

- Language Deficits: Lack of vocabulary impedes forming and retrieving autobiographical memories.

- Underdeveloped Sense of Self: Without a robust self-concept, events don’t embed in a personal narrative.

- Cultural Influences: Cultures that emphasize storytelling and reflection can prompt earlier childhood memories.

These key points capture the essence of why most people can’t remember events before age two, highlighting the synergy between neurological growth, language acquisition, and self-awareness.

Common Misconceptions About Infantile Amnesia

Myth-Busting: “Early memories are repressed due to trauma”

Freud popularized the notion that infantile amnesia arose from repression of early sexual or aggressive impulses. Modern neuroscience, however, emphasizes biological and cognitive immaturity, not psychological defense mechanisms.

Myth-Busting: “Some geniuses can recall their infancy perfectly”

Is it possible for a rare child prodigy to vividly remember being in a crib? Genuine cases are extremely questionable. While highly exceptional memory abilities do exist (like hyperthymesia), these typically involve events after language and self-concept are established.

Myth-Busting: “If you try hard enough, you can remember infancy”

Despite numerous techniques claiming to “unlock” infant memories, robust scientific evidence suggests these recollections aren’t just hidden—they were never fully consolidated. Once those neural traces are erased or overwritten, the original events remain irretrievable.

The Window of Infant Amnesia

Infantile amnesia generally spans birth to about age two or three, though this boundary isn’t rigid. Some children may claim to recall events from age two-and-a-half, while others retain only a few flashes from age four. Individual differences abound, influenced by genetics, environment, and the sheer randomness of memory.

For many people, a clear, stable childhood memory emerges closer to age four or five. This might involve a big moment like starting preschool, a holiday celebration, or a minor accident like scraping a knee—experiences often recounted by parents or captured in photos that help reinforce the memory.

Why This Matters for Adult Life

While it might seem trivial that adults can’t remember their first birthday, the implications extend to understanding human memory and learning as a whole. Recognizing that memories aren’t formed or stored in a vacuum helps us appreciate how experiences shape us, even subconsciously.

Moreover, it underscores the significance of early childhood care. Even though a toddler might not retain a detailed mental movie of story time, the neural groundwork laid during these interactions profoundly influences language, emotional development, and even future academic performance.

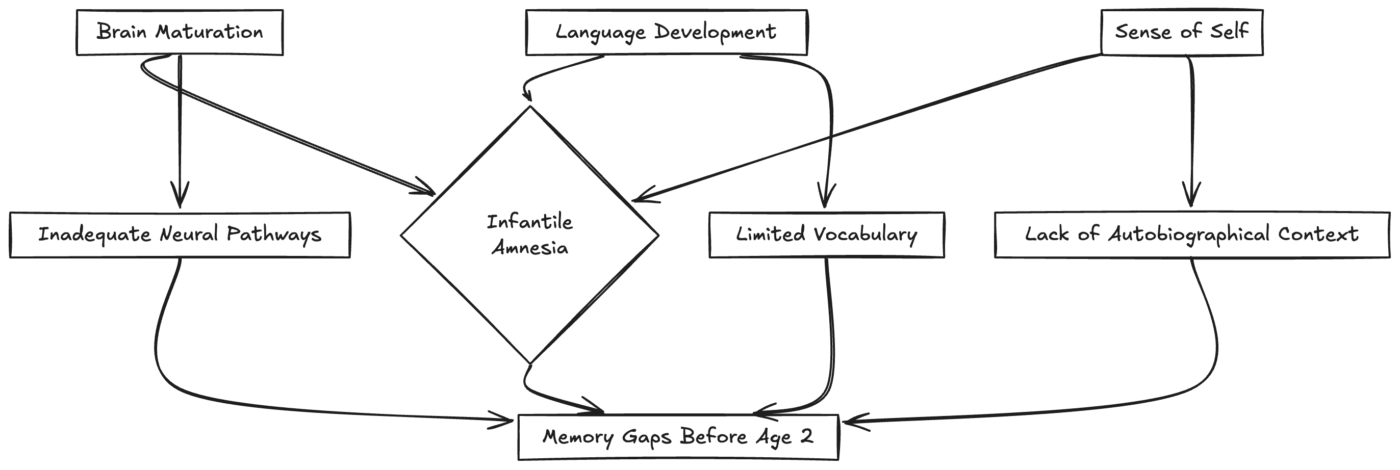

Diagram: Factors Influencing Infantile Amnesia

Here’s another visual that combines the major factors contributing to infantile amnesia into one branching structure.

Diagram: The Confluence of Factors

As you can see, each factor—brain maturation, language development, and sense of self—feeds into the overarching phenomenon we call infantile amnesia.

Emotional Learning vs. Cognitive Memory

Infants are extremely adept at learning through emotional cues, recognizing facial expressions, and responding to tone of voice. However, these emotional templates are typically stored in areas of the brain different from the explicit memory regions. This discrepancy helps explain why a baby can quickly learn whom they trust but later can’t describe a single event that shaped that trust.

Genes vs. Environment: Which Matters More?

Genetics certainly influence the development rate of the hippocampus and other brain areas tied to memory. Some children show advanced neural connections early on, while others develop more gradually. Still, environment—particularly enriching interactions like conversation, reading, or guided play—helps refine these connections and fosters better recall after age two.

Evolutionary Perspectives

Some researchers propose that infantile amnesia might be evolutionarily adaptive. Before advanced language or a clear sense of self, it’s more crucial for a baby to master immediate survival tasks than to store elaborate recollections. Additionally, the high neuroplasticity that characterizes infancy could be pivotal for rapid learning of fundamental skills, overshadowing the need for storing personal memories.

Implications for Childhood Education

Understanding how memory develops can reshape early education policies. High-quality infant and toddler programs often emphasize hands-on, interactive experiences rather than rote memorization. Such environments harness brain plasticity to build a strong foundation for future cognitive tasks.

Recognizing that children can’t reliably remember explicit events from infancy encourages educators and parents to focus on skill-building—motor skills, language exposure, social-emotional regulation—instead of trying to “teach facts” that a baby’s memory can’t retain anyway.

Addressing Parental Concerns

Parents sometimes feel guilty or anxious when they realize their kids won’t remember these precious infant moments. In reality, the emotional bond formed during infancy has lasting value. Even if the child won’t recall details of a family vacation at 18 months, the nurturing interactions support healthy brain architecture and emotional security.

Do Some Memories Survive in Another Form?

A growing body of research suggests that while explicit memories from infancy fade, they might resurface as implicit biases, emotional reactions, or body memories. For example, if an infant developed a positive association with bath time, they might continue to love water sports or swimming later, without knowing exactly why.

Trying to Catch the Fleeting Moments

Many parents document these fleeting years through photos, videos, or detailed journals. Some believe that by repeatedly showing these materials to a toddler, they can “implant” the memory. While it might help older toddlers remember aspects of an event around ages three or four, truly infant experiences—under 18 months—usually remain hazy because the critical memory-making apparatus wasn’t fully engaged yet.

Spotlight on Research Studies

A 2014 study in the journal Memory found that the average age of a person’s earliest memory is around 3.5 years, but over time, people think these events happened even earlier than they really did. This phenomenon of telescoping indicates that our sense of time and memory is flexible and prone to error.

Another study by neuroscientist Patricia Bauer noted that children could recall certain events if prompted with cues shortly after the event happened. However, once too much time passed—and as rapid brain development continued—those memories were usually inaccessible.

Leveraging Insights into Therapy

For children or adults dealing with early-life trauma, understanding infantile amnesia can guide therapeutic approaches. Therapists often focus on present emotions and behaviors linked to past events rather than trying to recover lost infant memories. This can be more effective than purely memory-based interventions.

Long-Term Influences on Personality

Even though explicit memories are scarce, the emotional and relational context of infancy leaves its mark. Stable attachment styles formed in infancy can influence personality development, social behaviors, and stress responses later in life—even if the child can’t recall the exact events that shaped these attachments.

When Does Memory Start “Sticking”?

While no magic switch flips at age two, memory retention tends to improve between ages two and four, coinciding with language bursts and the emergence of self-awareness. You’ll notice toddlers discussing what happened yesterday or last week—a clear sign that their brain is now storing and retrieving experiences more effectively.

This emergent narrative sense accelerates around age three to four, allowing children to recall family vacations, birthday parties, or visits to relatives. Those memories often become core narratives of their childhood, even if the details fuzz out over time.

Summarizing the Science

In essence, infantile amnesia arises from immature brain circuits, minimal language skills, and an underdeveloped sense of self. Our infant brains are wired for massive growth and reorganization, prioritizing survival and foundational learning over forming vivid autobiographical memories. While some implicit learning does occur, the explicit details of those earliest years usually vanish.

But there’s a positive side. By focusing on interactive experiences, emotional security, and rich language input, caregivers lay the groundwork for strong cognitive development. Those intangible seeds eventually blossom into robust childhood memories—just not the ones from that fleeting window before age two.

Read more

- Memory: From Mind to Molecules by Larry R. Squire and Eric R. Kandel

- The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are by Daniel J. Siegel

- The Hidden Brain by Shankar Vedantam

These resources delve deeper into the neuroscience and psychology of memory, offering a window into the fascinating science of early development.