TL;DR: Ocean tides ebb and flow mainly due to the Moon’s gravitational pull on Earth’s waters, combined with the influence of the Sun and Earth’s rotation.

The Gravitational Ballet Behind Ocean Tides

Why do waves gently creep up the shoreline, pause, then retreat back into the vast blue beyond? This regular rise and fall of sea levels—what we call tides—is not random. It’s a global rhythm set in motion by gravity, Earth’s rotation, and the subtle interplay between our planet, its Moon, and the Sun.

The simplest answer is that tides result from lunar gravity tugging at Earth’s oceans. But the fuller picture is more elegant and involved. Both the Moon and the Sun affect sea levels, though the Moon, being closer, has the stronger pull. Earth’s rotation and the ocean’s inertia add complexity, leading to the familiar ebb and flow that coastal communities witness twice a day.

Imagine stretching a rubber band around a basketball. Where you pinch and pull at one spot, the rubber band stretches toward you. Similarly, the Moon’s gravitational pull tugs at the oceans, creating a bulge, or tidal bulge, in the water. Because Earth spins on its axis, most coastlines pass through two such bulges every 24 hours or so, resulting in two high tides and two low tides daily. The result is a steady, rhythmic beat that has influenced coastal life for billions of years.

From Newton to Now: Understanding the Forces at Play

Gravity and Ocean Bulges

Think of the Earth’s oceans as a flexible envelope of water, always shifting and reshaping in response to gravitational forces. The gravitational pull of the Moon acts on all parts of Earth, but it’s more noticeable in the oceans because water is fluid and can move more easily than solid rock.

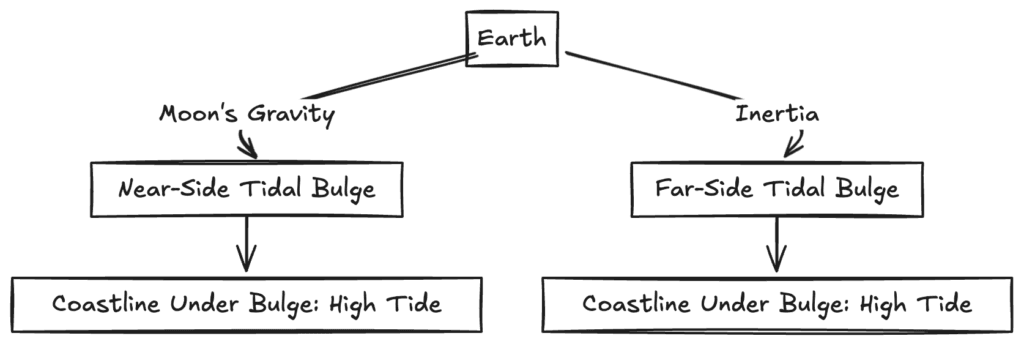

On the side of Earth closest to the Moon, the Moon’s gravity tugs the ocean surface upward, producing a high tide. On the opposite side, a less intuitive effect occurs. The Moon also pulls on Earth’s center of mass, effectively leaving behind water that’s slightly “flung outward” due to inertia. This creates a second bulge on the far side. Thus, at any given time, Earth is dressed in not just one, but two tidal bulges, one facing the Moon and one facing away.

The Earth rotates beneath these bulges. Coastal areas therefore move into and out of these raised sea levels. This rotation is why coastal regions typically experience two high tides and two low tides each day. It’s a dynamic dance, with the planet spinning, the Moon orbiting, and the oceans responding fluidly to every shift.

The Sun’s Influence

Although the Moon is the primary force, solar gravity also plays a role in tides. The Sun is far more massive than the Moon, but because it’s about 400 times farther away, its effect on tides is weaker. Still, the Sun’s gravitational pull aligns with or opposes the Moon’s influence periodically.

When the Sun, Moon, and Earth line up—during full moons and new moons—the tidal effects add up. High tides become even higher, and low tides become lower, resulting in what we call spring tides. When the Sun and Moon are at right angles relative to Earth—around the quarter phases of the Moon—their influences partly cancel out. The result is more moderate high and low tides, known as neap tides.

The Role of Earth’s Rotation and Orbital Dynamics

Why Two Tides a Day?

It might seem puzzling that we get two high tides and two low tides a day, rather than just one of each. The key lies in that second bulge on the opposite side of Earth. While one bulge is explained by the Moon’s gravitational pull, the other stems from inertia—a kind of balancing act.

Imagine Earth and the Moon as dancers connected by an invisible elastic band. They both orbit a common point called the barycenter, which lies inside Earth but not at its center. Because Earth is rotating around this barycenter, the oceans experience a slight outward pull on the side opposite the Moon. This creates the second tidal bulge.

As Earth rotates on its axis (once about every 24 hours), any given point on Earth’s surface passes through both bulges. Thus, as your coastline faces the Moon, you have a high tide; about half a day later, when your coastline faces away from the Moon, you encounter the other bulge’s high tide.

Earth’s Shape and Ocean Depth

The planet isn’t just a perfect sphere with uniformly deep oceans. Continental shelves, coastlines, and basin shapes all influence how tides behave. Narrow inlets or bays can amplify tidal heights, while broad, shallow shelves can slow the movement of tidal bulges.

If Earth were perfectly smooth and covered entirely by a uniform ocean, the tidal pattern would be simpler. But our actual planet is a patchwork of coastlines, islands, and varying seabeds. These imperfections cause differences in timing, tidal ranges, and even the number of daily tides some locations experience.

Diagram: The Gravitational Interaction

The relationship among Earth, Moon, and the resulting tidal bulges can be visualized with a simple diagram.

Diagram: How the Moon’s Gravity Creates Two Tidal Bulges

Seasonal and Geographic Variations in Tides

Latitude and the Tidal Cycle

Your position on Earth affects the character of your local tides. High-latitude regions (closer to the poles) can experience different tidal patterns compared to tropical or mid-latitude regions. The Earth’s tilt and the Moon’s orbit introduce a complexity that sometimes results in diurnal tides (one high tide and one low tide per day), semidiurnal tides (two nearly equal high and low tides per day), or mixed tides (two unequal high and low tides per day).

For example, the Bay of Fundy in Canada is famous for having some of the highest tides in the world, partly due to its funnel-shaped inlet amplifying the tidal wave. Meanwhile, some Pacific islands might see less dramatic changes in sea level, with relatively gentle tidal swings.

Seasonal Alignments

As Earth orbits the Sun, seasonal variations can slightly alter the distance between Earth and the Sun, as well as the angle at which the Sun and Moon align. These subtle shifts affect tides. In some places, you might notice slightly more pronounced tides during certain times of the year. For instance, when Earth is at perihelion (closest to the Sun, around early January), solar influence on tides is a bit stronger. Around aphelion (when Earth is farthest from the Sun, around early July), this influence is weaker.

These differences may be small compared to the daily and monthly tidal changes, but over time, they add another layer of complexity to the tidal picture. Our oceans are constantly dancing to the gravitational tunes of the Moon and Sun, with Earth’s own orbital quirks adding subtle accents.

Sun and Moon Alignments: Spring and Neap Tides

Spring Tides: Boosted by Alignment

Twice a month, when the Earth, Moon, and Sun line up—during full and new moons—we experience spring tides. This doesn’t mean “spring” the season, but rather that the tides “spring forth” to greater heights. High tides climb higher than average, while low tides dip lower, making the tidal range more dramatic.

These extra-strong tides occur because the gravitational pulls of the Moon and Sun reinforce each other. Think of two people pulling on the same rope in the same direction. The combined effort yields a bigger outcome. Similarly, the Moon and Sun pulling in line amplify the ocean’s response, resulting in higher highs and lower lows.

Neap Tides: A More Moderate Scenario

About one week after a spring tide, the Moon and Sun arrange themselves at right angles. At these times—when the Moon is in its first or third quarter phase—their gravitational pulls partly counteract each other, leading to neap tides. High tides aren’t as high, and low tides aren’t as low, making the tidal range more modest.

To return to our rope analogy, this is like two people pulling on a rope in opposing directions. They don’t completely cancel each other out, but the net effect is smaller. That’s what happens during neap tides, and it gives us a break from the more dramatic sea-level changes witnessed during spring tides.

Tidal Resonance and Coastal Amplification

Resonance in Tidal Basins

Some coastlines experience unusually large tides because of tidal resonance, a phenomenon where the natural frequency of water movement in a basin or channel aligns with the tidal forcing frequency. If Earth were the size of a basketball, imagine tapping it repeatedly with a specific rhythm—sometimes the water inside a hypothetical shell would slosh back and forth more intensely if you matched the right rhythm. This “matching of rhythm” can happen in places like the Bay of Fundy, causing exceptionally large tides.

In essence, resonance means the coastal basin’s shape and size interact with incoming tidal waves in a way that amplifies them. This leads to tidal ranges that can exceed 10 or even 15 meters in some places, dwarfing the more modest tides found along many other coastlines.

Underwater Topography and Funnel Effects

Beyond resonance, other factors like underwater ridges, continental shelves, and coastline shape also play roles. Narrow, tapering bays can compress tidal energy into a smaller space, making the tide climb higher as it travels inland.

Consider a funnel: you pour water into the wide end, and as it narrows, the flow speeds up and the water level rises. Coastal geographies can act like natural funnels for tidal waves, producing dramatic rises in sea level that can transform a simple beach into a scene of surging tidal streams.

The Earth-Moon-Sun Connection Over Time

The Changing Distance to the Moon

Did you know that the Moon is gradually receding from Earth at about 3.8 centimeters per year? Over millions of years, this slow drift affects tides. When the Moon was closer billions of years ago, tides were likely much more powerful. Life’s early evolution may have been influenced by these more energetic tidal cycles, potentially aiding nutrient mixing and offering dynamic coastlines as evolutionary hotspots.

Looking far into the future, if the Moon continues its gradual retreat, tidal ranges might decrease, altering the long-term fate of our coastal zones. The stability we see today is just a snapshot in a long cosmic story.

Milankovitch Cycles and Tidal Patterns

On even longer timescales, Milankovitch cycles—changes in Earth’s orbit and tilt—can influence climate and ocean circulation patterns. While these cycles are more often discussed in relation to ice ages and global temperatures, they can also subtly affect how and where tides are most pronounced. Over tens of thousands of years, slight shifts in Earth’s orientation might change tidal patterns, redistributing tidal energy and influencing coastlines over geological timescales.

Life in Tune with the Tides

Ecosystems Dependent on Tidal Rhythms

Many coastal ecosystems depend on tides like clockwork. Mangroves, salt marshes, and intertidal zones rely on regular flooding and draining to support a rich diversity of life. Consider small creatures that cling to rocks along the shore. They depend on twice-daily baths of nutrient-rich seawater. Tiny fish and crustaceans time their feeding and breeding with the tide’s schedule, while migrating birds plan their layovers at mudflats exposed by low tides.

Tides have shaped human life, too. Fishing villages adjust their schedules to the tides, boats use high tides to navigate shallow harbors, and coastal engineers plan structures with the ebb and flow in mind. Tidal energy is even harnessed to generate electricity in some places, transforming gravitational rhythms into renewable power.

Tides as Evolutionary Drivers

For billions of years, life has danced with the tides. Some scientists suggest that early life’s transition from the ocean to land may have been eased by tidal zones that periodically exposed organisms to air, encouraging adaptations for terrestrial living. The gentle pull and release of the sea could have played a role in shaping life’s grand storyline.

Misconceptions and Myths About Tides

Myth: The Moon Directly “Lifts” the Water

A common misconception is that the Moon’s gravity directly “pulls” water up from Earth’s surface like a hand picking up an object. In reality, it’s more complex. The Moon’s gravity stretches the entire Earth-Moon system, affecting both the water on the near side and creating an inertial bulge on the far side.

The result is not just one big wave following the Moon around, but a stable set of bulges formed from gravitational and inertial forces. Earth’s rotation carries coastlines through these bulges.

Myth: Tides Are the Same Everywhere

Many people assume that every coastline experiences the same pattern of two equal high and low tides daily. In fact, tides vary widely. Some places see one major high tide and one minor high tide a day, others have a clean two-high, two-low pattern, and some coastlines have more irregular patterns.

Local geography, ocean currents, wind, and atmospheric pressure can all alter tidal patterns. The complexity beneath the surface is immense, making tides unique to each region.

Myth: Only the Moon Matters

While the Moon is the primary tidal influencer, the Sun also plays a major role. In combination, the Moon and Sun give us spring and neap tides. Without the Sun’s contribution, our tides wouldn’t have the same dynamic range. The interplay of lunar and solar gravity is key to understanding the full picture of tidal rhythms.

Human Interaction and Tidal Awareness

Navigating by Tides

For coastal communities, knowledge of tides is essential. Fishermen use tide tables to decide when to head out to sea. Beachcombers check tidal schedules to reach tide pools at their most accessible times. Cargo ships wait for high tides to enter shallow ports safely.

Modern navigation instruments and online tide charts make it easier than ever to plan around the tides. Yet for centuries, sailors, farmers, and coastal dwellers relied on intuition, local knowledge, and careful observation to time their activities. Even today, there’s a sense of wonder in watching the tide come in and go out, as reliable as a cosmic heartbeat.

Tidal Energy as a Resource

Tides are a source of renewable energy. Tidal power plants in places like France’s Rance River estuary harness the rise and fall of the ocean to generate electricity. Unlike wind or solar power, tides are highly predictable, making them a potentially steady source of green energy. As technology advances, more regions may tap into this gravitational gift to reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

Cultural and Historical Significance of Tides

Tides in Ancient Navigation and Calendar Systems

Long before satellites and smartphones, people watched the tides to understand the cosmos. Ancient mariners noted tidal patterns to navigate unfamiliar coasts, while some cultures tied their lunar calendars to tidal cycles, observing that certain events—like spawning fish or the arrival of migratory birds—synced with tidal extremes.

The word “tide” itself shares roots with the concept of “time,” reflecting how deeply this phenomenon is interwoven with human understanding of daily, monthly, and seasonal cycles.

Symbolism and Folklore

In literature and folklore, tides often symbolize change, renewal, or the passage of time. Poets and storytellers have drawn on the steady ebb and flow to underscore themes of life’s impermanence, the interplay of forces seen and unseen, and the idea that nature’s rhythms persist regardless of human wishes.

Just as ancient peoples invested stars and planets with meaning, they also recognized the tides’ cosmic connection. The Moon, luminous and mysterious, became tied to the ocean’s pulse, influencing religious rituals, agricultural practices, and community gatherings that celebrated life’s cycles.

The Science of Measuring and Predicting Tides

Tide Gauges and Satellites

Today, tide prediction is a precise science. Tide gauges placed along coastlines record sea levels over time. By analyzing the patterns, scientists can predict future tides with remarkable accuracy. Satellites and GPS measurements provide even more detail, enabling improved forecasts and supporting maritime industries, coastal planning, and climate change research.

Using Models and Harmonic Analysis

Scientists apply harmonic analysis, breaking down tidal patterns into component frequencies related to the positions and movements of Earth, Moon, and Sun. By understanding these components, tide prediction software can forecast tides years—or even decades—into the future.

This ability to anticipate tides helps protect coastal areas from flooding, guide infrastructure projects, and inform coastal ecosystem management. Knowing when and how the sea will rise and fall is critical in a warming world, where rising sea levels are already reshaping shorelines.

Tides in a Changing Climate

Rising Sea Levels and Extreme Tides

As the planet warms and ice caps melt, sea levels creep higher. This means that future high tides could be higher than ever before. Coastal flooding during storms or king tides—unusually high tides that occur when the Moon is closest to Earth—may become more frequent and severe.

For coastal cities, understanding tides is now more urgent than ever. From building sea walls to restoring wetlands that act as natural flood defenses, communities must factor tides into their resilience plans. A small change in baseline sea level can turn a manageable high tide into a destructive event.

Altered Tidal Patterns

Climate change also affects ocean currents and atmospheric conditions. These changes can modify how tidal waves propagate, potentially altering tidal patterns and affecting marine life. Coastal habitats, like coral reefs and mangroves, depend on stable tidal cycles. Disruptions could ripple through entire ecosystems, affecting fisheries, tourism, and local economies.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Causes Tides?

Short Answer: Tides are caused by the gravitational pull of the Moon and the Sun on Earth’s oceans, combined with Earth’s rotation.

Longer Explanation: The Moon’s gravity pulls water toward it, creating a bulge of water known as a high tide. On the opposite side of Earth, inertia creates a second bulge. As Earth spins, coasts pass under these bulges, experiencing two high tides and two low tides per day.

Why Are There Two High Tides a Day?

Because Earth rotates beneath two tidal bulges—one facing the Moon and one on the opposite side—most places see two high tides daily. One results from the Moon’s gravitational pull, the other from the inertia of Earth rotating around the Earth-Moon barycenter.

What Are Spring and Neap Tides?

Spring tides occur when the Earth, Moon, and Sun align during full or new moons, making high tides higher and low tides lower. Neap tides occur when the Moon and Sun are at right angles, producing more moderate tidal ranges.

Why Do Some Places Have Bigger Tides Than Others?

Local geography plays a major role. Funnel-shaped bays, underwater ridges, and resonant frequencies in coastal basins can amplify tides, leading to exceptionally high tidal ranges, as seen in the Bay of Fundy.

How Do Tides Affect Marine Life?

Many coastal ecosystems depend on regular tidal cycles to deliver nutrients, flush out waste, and create diverse habitats. Intertidal species, such as barnacles and mussels, rely on the ebb and flow for feeding and reproduction.

Are Tides Changing Over Time?

Over long timescales, yes. The Moon is slowly moving away from Earth, which can alter tidal ranges in the distant future. Climate change and rising sea levels may also make high tides higher and increase coastal flooding risk.

Can We Use Tides to Generate Energy?

Yes. Tidal energy can be harnessed using turbines and barrages. Since tides are predictable, tidal power provides a stable source of renewable energy that can complement wind and solar resources.

Do Tides Happen Only in Oceans?

Large lakes can experience very small tides, but they’re usually insignificant compared to ocean tides. The vastness of oceans allows water to move freely in response to gravitational forces, creating noticeable tidal bulges.

Read more

- “Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean” by Jonathan White (Amazon)

- “The Book of Tides” by William Thomson (Amazon)

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for real-time tidal data and educational resources.

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) for research on ocean dynamics and tidal phenomena.