TL;DR: Humans dream largely because our brains remain active during sleep, processing emotions, memories, and problem-solving tasks through vivid mental imagery.

Unraveling the Mystery of Why We Dream

Humans have long been fascinated by dreams—those fleeting, sometimes bizarre narratives that unfold behind our eyelids each night. Philosophers and scientists alike have proposed countless theories, ranging from emotional release to neurological housekeeping. While we still don’t have a definitive, one-size-fits-all explanation, modern research sheds considerable light on how dreams form and why they might matter to our mental and emotional well-being.

In essence, dreaming involves the complex interplay of brainwaves, chemicals, and memory networks during various sleep phases. We spend roughly a third of our lives sleeping, and a substantial fraction of that time is spent dreaming—especially during REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep. Though we occasionally recall vivid storylines or illusions, many of our dreams vanish upon awakening. Yet the question remains: Why do humans dream, and what drives the brain’s nightly foray into this surreal realm?

The Brain in Sleep Mode

Sleep Stages and Dreaming

Sleep isn’t just a single state; it’s composed of distinct phases. We cycle through NREM (Non-Rapid Eye Movement) stages—often labeled N1, N2, N3—and the REM stage, approximately every 90 minutes. Although some dreams arise in NREM phases, REM sleep is most famously associated with lively, story-like dreams.

REM Sleep stands out for its heightened brain activity. You might imagine REM as a paradoxical phase, because the brain looks almost as active as in wakefulness, yet the body remains in a state of temporary paralysis to prevent acting out our dreams. This combination of immobilized muscles and an active, imaginative mind sets the stage for dynamic dream experiences.

Brain Regions at Work

During REM sleep, the limbic system (responsible for emotion and memory) becomes highly active, while certain areas of the prefrontal cortex (involved in logical reasoning and impulse control) show reduced activity. This imbalance could explain why dreams often feel emotionally charged yet lack the critical thinking that might question illogical scenarios. The chemical environment also shifts. Key neurotransmitters like acetylcholine rise, while serotonin and norepinephrine levels dip, possibly influencing the whimsical, non-rational nature of dreams.

Theories on Why Humans Dream

Scientists approach the mystery of dreaming from multiple angles. Below are some leading theories that try to explain why we dream—though it’s worth noting that these theories aren’t mutually exclusive, and dreams might serve more than one function.

Memory Consolidation

One widely accepted notion is that the brain uses dream states to reinforce or prune connections tied to memories. Think of it like a nightly update for your mental “hard drive.” As you sleep, your brain replays certain experiences, deepening crucial neural pathways and discarding unnecessary details. Dreams might reflect the emotional highlights of the day, helping the brain store relevant lessons and memories for future reference.

Emotional Regulation

Another perspective emphasizes emotional processing. Our minds replay stressful or emotionally charged events in a less threatening, dream-like environment, potentially allowing us to work through unresolved feelings. Dreams can also incorporate bizarre elements or blend real-life scenarios in unexpected ways, helping to desensitize or reframe strong emotions. In short, dreaming could be a built-in system for overnight therapy.

Threat Simulation

Some evolutionary psychologists propose that dreams evolved as a form of threat simulation, a safe environment for rehearsing responses to dangers. In a primitive sense, if you dream of running from predators or facing conflicts, you might be unconsciously practicing how to handle real-life threats. This notion aligns with the observation that many dreams contain negative or anxiety-inducing themes, prompting us to refine coping strategies without actual risk.

Creative Problem-Solving

Dreams aren’t always nightmares or memory replays. Sometimes they produce innovative ideas or metaphorical insights. Historically, inventors, artists, and scientists have cited dream-inspired breakthroughs. The unconstrained nature of dreaming, where logical barriers soften, could foster creative leaps. By temporarily sidelining the rational, vigilant prefrontal cortex, the brain may piece together novel combinations or solutions.

Neural Housekeeping

A simpler, more mechanical view suggests that dreams arise from random neural firings as the brain reorganizes itself overnight. According to the activation-synthesis hypothesis, the pons (a region in the brainstem) sends spontaneous signals through the cortex, and the brain “synthesizes” these signals into a storyline—our dream. While this framework doesn’t exclude other functions, it emphasizes that dream content may be partly an accidental byproduct of the nightly neural clean-up.

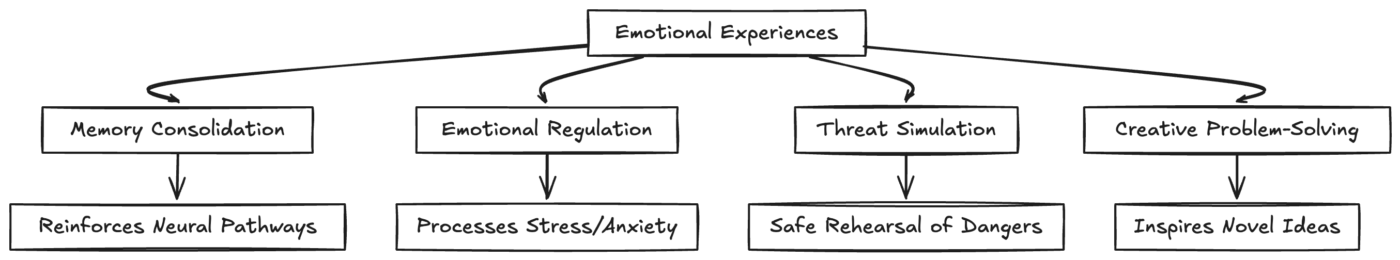

Diagram: Possible Functions of Dreaming

Diagram: Dream Function Paths

Diagram Explanation: This flowchart shows how emotional experiences (A) feed into multiple dream functions—from memory and emotion processing to threat simulation and creativity. Each arrow highlights a possible benefit or outcome of dreaming.

The Biology Behind Dream Creation

REM Sleep Mechanisms

During REM sleep, your brainstem inhibits most muscle movement, preventing you from physically acting out dream scenarios. Meanwhile, the visual cortex becomes active even without external input. This leads to vivid imagery in your dreams. The hippocampus, central to memory, also lights up, linking dream content to personal experiences.

Neurotransmitters and Hormones

- Acetylcholine: Maintains high levels in REM, stimulating brain activity and vivid imagery.

- Serotonin and Norepinephrine: Drop in REM, possibly reducing rational oversight.

- Dopamine: May boost during certain REM segments, relating to the emotional and motivational aspects of dreams.

This “chemical cocktail” fosters a unique mental landscape where fantasies, emotions, and old memories can combine.

Myths vs. Reality About Dreaming

Myth: We Only Dream in Black and White

Reality: Research indicates most people dream in color. Historical claims about black-and-white dreams might trace back to black-and-white films or media influences. Even when color isn’t the focus, many dreamers sense a rich visual palette.

Myth: If You Die in a Dream, You Die in Real Life

Reality: Countless people report dreaming their own demise and waking up just fine. Dreams can be intense, but they don’t have the power to literally end your life.

Myth: REM Sleep Is the Only Time We Dream

Reality: While REM dreams are often more vivid, dreaming can occur in NREM stages too—just typically more fleeting and less elaborate.

Relatable Comparisons

- Emotional Debrief: Think of dreaming as a nightly “talk-it-out” session, where your brain recaps the day’s events and finds closure on stressful incidents.

- File Archiving: Dreams can act like a computer’s background process, deciding which files (memories) to keep, store in a separate folder (long-term memory), or delete.

- Psychological Sandbox: Much like kids playing pretend to develop social skills, dreams let your psyche safely explore different realities or fears, honing emotional resiliency.

The Spectrum of Dream Types

Lucid Dreams

A lucid dream occurs when you realize you’re dreaming and can sometimes control the narrative. This state arises when parts of the brain associated with self-awareness “wake up” during REM, bridging the gap between sleep and consciousness. Lucid dreamers often practice reality checks throughout the day or use specialized techniques before bedtime to trigger awareness in dreams.

Nightmares

A nightmare is a distressing dream that typically jolts you awake. They often revolve around fear, anxiety, or unresolved trauma. Chronic nightmares may link to stress, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or certain medications. They serve as a stark example of how dreams can reflect internal emotional conflicts or anxieties.

Recurring Dreams

Many people experience recurring dreams, featuring repeated scenarios like taking a test unprepared or running in slow motion. Recurrences might suggest unfinished psychological business or unaddressed stressors. While not always identical, these dreams share core themes that point to unresolved issues or persistent concerns.

Daydreams

Although not part of traditional sleep, daydreams are short mental detours into imagined scenarios when you’re awake. They share some creative features with sleep-based dreams but lack the structured phases of REM or NREM. Daydreaming can boost problem-solving, but it can also distract from immediate tasks.

Dream Research and Psychological Perspectives

Freudian and Jungian Views

Historical psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud believed dreams were the “royal road” to the unconscious, revealing hidden desires and conflicts. Carl Jung proposed dreams carry archetypal symbols bridging personal and collective unconscious content. While these classic theories lack robust scientific backing, they continue to influence dream interpretation and popular culture.

Cognitive and Behavioral Studies

Modern psychologists often use cognitive-behavioral frameworks to understand how dreams reflect daily experiences. Laboratory studies might wake subjects during REM intervals to document dream reports, linking them to preceding emotional states. Patterns emerge—like stress influencing negative dream content or newly learned tasks appearing in dream fragments.

Neuroscientific Insights

Neuroimaging techniques like fMRI and PET scans allow researchers to watch the brain in action during REM. These methods reveal how emotional centers remain active while rational oversight dims. The result is an environment conducive to intense emotional storytelling—our dreams.

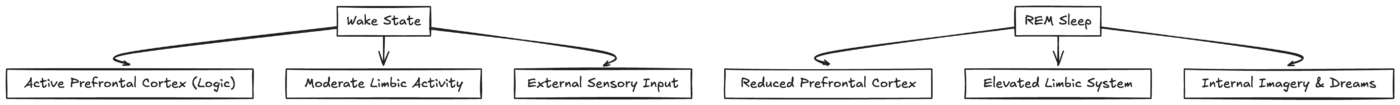

Diagram: Brain Activity in Dreaming vs. Wakefulness

Diagram: Dreaming vs. Awake Brain

Diagram Explanation: When awake, the prefrontal cortex (B) is highly active, aiding logical thinking. In REM (F), it scales down, while limbic regions (G) fire up, fueling dream scenarios (H).

Dreams, Mental Health, and Learning

Mental Health Connections

In the realm of mental health, dream content can reflect anxiety, depression, or unresolved trauma. Therapists sometimes use dream analysis to glean insights into a patient’s emotional landscape. Healthy sleep (with its full repertoire of dream phases) correlates with improved mood and emotional regulation, though dreams alone aren’t a magic cure.

Learning and Skill Reinforcement

Research hints that dreaming about a newly learned skill—like playing a musical instrument or solving math problems—can boost memory retention. Dreams appear to reinforce neural circuits, helping us cement knowledge. The next time you’re cramming for a test, you might consider letting your dreams do some behind-the-scenes studying.

Creativity and Problem-Solving

Countless anecdotes describe authors, composers, and scientists who woke up with a dream-inspired solution. The free-associative nature of dreams can let the brain link ideas in unanticipated ways. This dream-fueled creativity can break through mental blocks—like a painter combining colors in a novel style after a dream or a songwriter capturing a haunting melody upon waking.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Why do some people never remember their dreams?

Many of us dream every night, but dream recall varies greatly. Some just wake up too abruptly or shift focus immediately, losing fragile memory traces. Keeping a dream journal by the bed and writing down snippets upon waking can improve recall.

Can dreams predict the future?

Most scientific evidence says no. While coincidental overlaps between dream events and reality happen, there’s no credible data showing dreams consistently foresee future specifics.

Does everyone dream in REM?

Yes, all humans experience REM sleep cycles unless a rare medical condition disrupts them. Even those who claim to never dream likely do, but forget upon waking.

Can external stimuli alter dream content?

Yes, external sounds (like an alarm clock’s ring) or bodily sensations (a full bladder) can weave into dream narratives. Temperature changes or even smells might color a dream’s storyline.

Are nightmares a sign of a serious problem?

Occasional nightmares happen to most people. However, frequent, distressing nightmares could indicate underlying stress, anxiety, or trauma. Seeking professional support can help if nightmares significantly disrupt sleep or daily life.

Practical Tips for Exploring Dreams

- Dream Journal: Keep a notebook or an app to capture any dream fragments immediately after you wake up. Consistent journaling enhances dream recall.

- Establish Regular Sleep Patterns: Adequate, consistent sleep promotes robust REM cycles, often leading to more vivid dreaming.

- Explore Lucid Dreaming: If intrigued, experiment with “reality checks,” like checking your watch or pinching your nose. Over time, you might recognize anomalies in dreams and gain limited control.

- Balanced Lifestyle: High stress or disrupted sleep can shift dream content toward negativity. Managing stress and prioritizing rest can cultivate calmer or more insightful dreams.

Myth-Busting: “Dreams Always Have Hidden Meaning”

Myth: Every dream you experience holds a coded message or a prophecy about your life.

Reality: While symbolic elements and reflections of personal concerns are common, not every dream is a cryptic puzzle. Much dream content might be random or fleeting mental associations without deep significance. Still, repeated themes can offer insight into emotional patterns.

Summarizing the Key Points

- REM Sleep forms the core stage of intense dreaming, fueled by high brain activity and reduced muscle movement.

- Emotional processing, memory consolidation, threat simulation, and problem-solving are leading theories for why we dream.

- Chemical changes in the brain during sleep create a unique environment where limbic systems fire up, while logical centers dial back.

- Neuroimaging reveals how dream states mirror aspects of wakeful cognition, except for a lack of external stimuli and dampened rational oversight.

- While some dreams might hold emotional or creative significance, others might be random outcomes of neural reorganization.

Final Thoughts on the Purpose of Dreams

Dreaming remains an endlessly intriguing frontier. Even in today’s era of brain scans and psychological models, certain elements of dream function stay elusive. Yet, it’s clear that dreams likely support emotional balance, memory formation, and potentially creative bursts. They offer a window into our private, unconscious world—a nightly stage where anxieties, hopes, and random fragments of daily life mix into sometimes meaningful, sometimes fantastical narratives.

Ultimately, why do humans dream? The simplest answer is that our sleeping brain remains active, weaving experiences, emotions, and neural signals into an imaginative tapestry that might benefit us psychologically and neurologically. As research continues, we’ll likely refine our understanding of this universal, yet deeply personal phenomenon.

Read more

- The Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud

A classic text that, despite outdated elements, historically shaped how we think about dreams and the unconscious. - Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker

Presents modern findings on sleep science, including a chapter dedicated to the functions of dreaming. - Dreaming: A Very Short Introduction by J. Allan Hobson

Offers a concise overview of dreaming through a neuroscientific lens, perfect for readers wanting more detail in a short format. - The Mind at Night: The New Science of How and Why We Dream by Andrea Rock

Explores various scientific studies on dreaming, tying them to broader questions about consciousness and mental health.