TL;DR: Our brains interpret the Moon against foreground objects and distance cues near the horizon, making it seem larger, even though its actual size never changes.

The Curious Phenomenon of the “Bigger” Moon

When you see a huge, glowing Moon resting on the horizon, it can seem downright gigantic. Yet a few hours later, high above your head, the same Moon might appear smaller and less impressive. This change in perceived size is commonly called the Moon Illusion. Crucially, the Moon isn’t actually changing size or distance. Instead, our minds are playing visual tricks on us.

Why do we consistently interpret the horizon Moon as significantly larger? Scientists have debated this for centuries, offering multiple explanations—ranging from atmospheric refraction to psychological perception. Modern research suggests that perceptual and cognitive factors carry most of the weight, while the atmosphere and our surroundings also contribute. It’s a perfect storm of the human brain, visual cues, and sometimes a little bit of optical physics.

How Our Brains Perceive Size

To understand why the Moon seems bigger near the horizon, we first need to explore how our brains gauge the size of objects. When we look at an object—like a car across the street—two pieces of information factor into our perception: the actual size of the image on our retina (the light-sensitive tissue at the back of our eye) and contextual cues that tell us how far away the object is.

The Retinal Image

The image of the Moon enters our eyes as light. The size of this image on the retina depends on the Moon’s angular diameter—how large it appears in the sky in terms of degrees of arc. Interestingly, the Moon’s angular diameter remains approximately the same whether it’s at the horizon or overhead. This means the “raw data” hitting our eyes doesn’t change much.

Distance Cues and the Brain’s Scaling

Our brains constantly interpret distances in the environment, using visual landmarks and depth signals. If we believe an object is farther away, the brain may interpret it as larger than the raw retinal image suggests. For example, a plane flying high might look tiny, even though we know planes are big. Likewise, the horizon is often perceived as being very distant, so the same angular size of the Moon is “scaled up” by our brain’s internal logic.

Key point: The Moon near the horizon is seen against buildings, trees, or mountains—familiar references that whisper, “This Moon is far away.” Our brain then does the mental math: a “far” object that creates the same retinal image as a “closer” object must be bigger. Overhead, the Moon typically has fewer reference points around it, so we perceive it as smaller.

Multiple Explanations Through History

Scientists have wrestled with the question of the Moon Illusion for centuries. Ancient Greek philosophers noted that the Moon at the horizon seemed larger. Early explanations ranged from atmospheric effects to changes in the Moon’s actual distance (even though its orbital variation is too subtle to cause such a dramatic difference).

Atmospheric Refraction

Many people assume that atmospheric refraction, a bending of light rays as they pass through thick layers of the atmosphere, magnifies the Moon on the horizon. While refraction does cause slight distortions—like flattening the lower portion of the Moon or Sun at sunrise or sunset—its effect on apparent size is minimal. It cannot, on its own, account for the significant difference we often perceive.

Ponzo Illusion and Related Phenomena

Leonardo da Vinci remarked on illusions in the 16th century, but it wasn’t until the 20th century that psychologists like Mario Ponzo described a classic illusion. In the Ponzo Illusion, two identical horizontal lines placed between converging parallel lines appear different in size because one line is judged as being “farther away.” Our brains essentially treat them as different in size due to perspective cues.

The Moon Illusion behaves similarly. Horizon elements like trees, hills, or buildings act like those converging parallel lines—our brain interprets the horizon as “far away,” so the Moon “must be bigger” if it has the same angular size. When the Moon is overhead, we lose those distance cues, and the raw angular size is interpreted more literally.

A Closer Look at the Horizon

The Horizon as a Depth Cue

When you stand on a flat expanse—like a wide field or a beach—you have a clear line where the sky meets the ground. This horizon line can be 5 kilometers (3 miles) or more away, depending on your elevation and the terrain. Everything near the horizon is typically farther away than overhead objects in our everyday experience.

This consistency in daily life—distant mountains, remote coastlines—trains our brains to interpret the horizon as “way out there.” So when the Moon sits on that line, we unconsciously apply the same logic and assume the Moon is also “way out there” in a more immediate sense, even though in cosmic terms, the difference in distance is negligible.

Foreground Objects

Adding to this, foreground objects like a row of trees or a city skyline provide contextual scale. Because we know the approximate size of a tree or building, seeing the Moon loom behind or beside these items amplifies the sense of the Moon’s largeness.

The Ebbinghaus Illusion and Relative Size

Another well-known phenomenon is the Ebbinghaus Illusion, where a circle surrounded by large circles looks smaller than an identical circle surrounded by small circles. With the horizon Moon, the sky around it might be filled with features (mountains, city skylines) that are physically huge but still dwarfed by the Moon in a relative sense. This mismatch can push our perception to make the Moon seem even larger.

By contrast, when the Moon is overhead, it’s surrounded by a vast expanse of sky with no immediate frame of reference. That emptiness can make the Moon look smaller. Think of it like setting the same piece of jewelry on a cluttered table versus on a clean, empty surface: it feels smaller or larger depending on the context, even if the object itself doesn’t change.

Is It All in Our Heads?

While psychological perception plays a major role, some slight physical factors also come into play:

- Atmospheric refraction slightly changes the apparent shape of the Moon near the horizon.

- Human posture and eye movement: Looking straight up at the sky might change how we focus on the Moon compared to looking straight ahead.

Still, decades of experiments show that the main culprit is the brain’s interpretation of distance and size, not major physical distortions.

Experiment at Home

A neat trick to prove the Moon’s size doesn’t change is to close one eye and hold out a small object—like a coin—at arm’s length, just covering the Moon’s disk. If you measure how big the coin appears against the Moon near the horizon versus overhead, you’ll find no significant difference in what’s needed to cover it. This test confirms that the angular size is essentially constant.

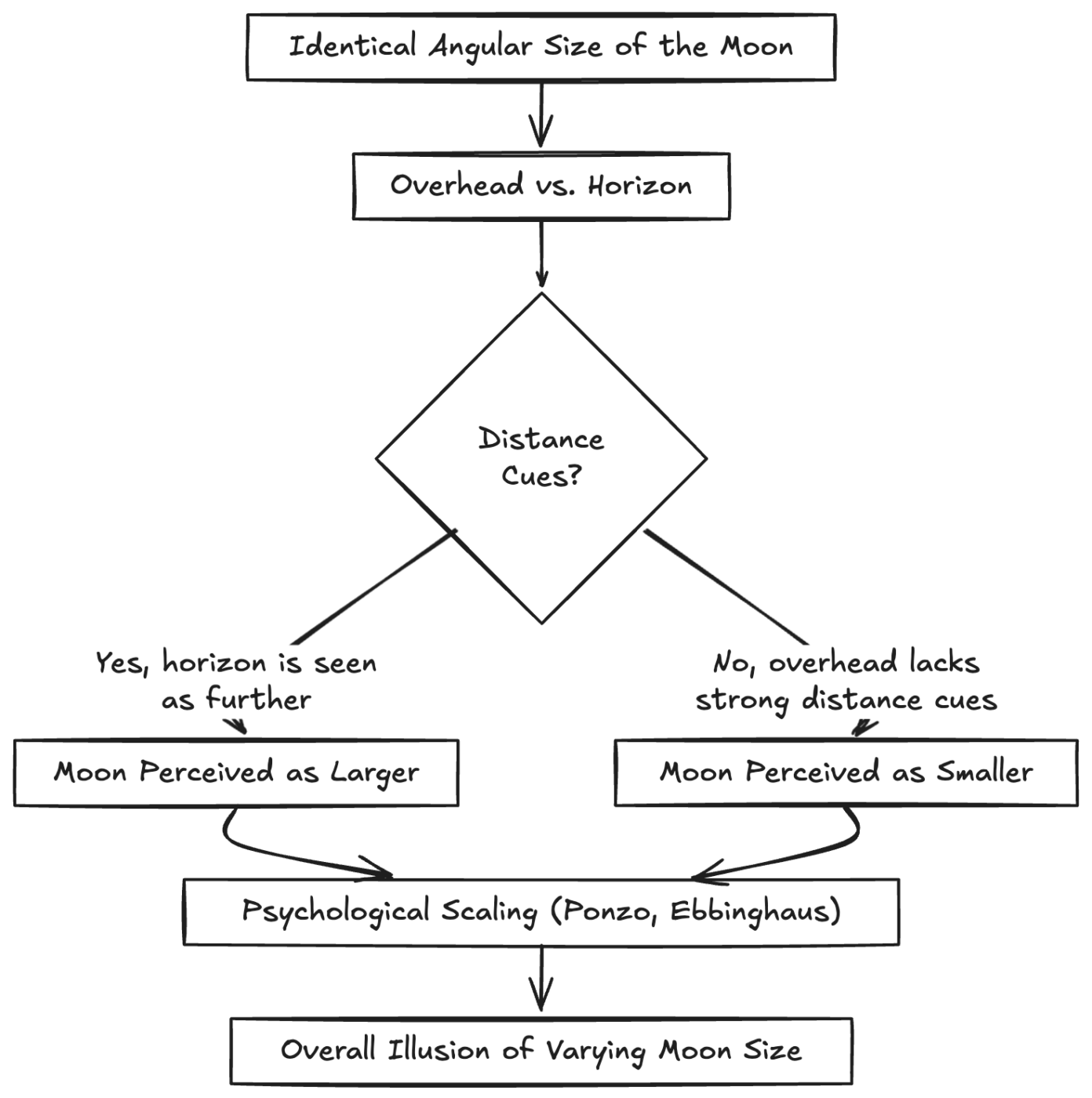

Diagram: Main Causes of the Moon Illusion

Diagram: The Interplay of Visual and Cognitive Factors

Here, the center question is whether strong distance cues are present. When the Moon is near the horizon, yes, we have strong distance references—so it looks bigger. Overhead, no, there are fewer reference points—making the same angular size appear smaller.

Debunking the “Atmospheric Magnification” Myth

Myth: The Earth’s atmosphere acts like a giant lens, magnifying the Moon when it’s near the horizon.

Reality: While the atmosphere refracts light, it doesn’t act like a magnifying glass that significantly enlarges the Moon. In fact, atmospheric refraction can slightly flatten the Moon’s lower edge at the horizon, but the overall size change from refraction is minimal—around 1-2% at most.

Why It Matters: Lessons About Perception

The Moon Illusion isn’t just a party trick; it showcases how our brains actively shape what we see. This phenomenon reminds us that perception is not just raw data from our eyes; it’s an interpretive process combining sensory input, memory, context, and expectation.

We see illusions in daily life all the time, from perspective drawings that fool us into perceiving 3D depth on a 2D page, to illusions in architecture where buildings look taller or shorter based on design. The horizon Moon is simply a dramatic and universally accessible example of how powerful these perceptual effects can be.

The Role of Beliefs and Expectations

Interestingly, cognitive expectation can enhance the illusion. When people know the Moon is “rising” and anticipate it might look big, they may pay extra attention to its size. Overhead, perhaps they’re used to seeing the Moon and don’t think twice, so their brain defaults to a more “normal” interpretation.

In some cultures, the “rising Moon” is an event—people watch it come up behind hills or over a lake. The cultural emphasis on the event can reinforce the impression that the Moon is supposed to be large and majestic at that time, heightening the psychological effect.

Relative Distances in Space

In reality, the Moon is about 384,400 kilometers (238,900 miles) away from Earth, whether it’s at the horizon or overhead. That distance doesn’t fluctuate significantly over a single night. In fact, the Moon does have a slightly elliptical orbit, which can cause some change in its actual size over the course of a month, but that’s a separate phenomenon. The difference there is about 14% between the closest (perigee) and farthest (apogee) approaches, and it occurs gradually—much less dramatic than the nightly horizon illusion.

If Earth were the size of a basketball, the Moon would be about the size of a tennis ball and placed roughly 7.3 meters (24 feet) away. This scale remains the same whether the Moon is at the horizon or high in the sky.

FAQs

Why do I see the Moon as bigger near the horizon even when I know it’s an illusion?

It’s a cognitive illusion deeply wired into how our brains perceive distance and size. Even if you logically know the Moon isn’t growing, your visual system still applies automatic scaling rules based on distance cues. Knowledge alone doesn’t override the effect.

Is there a way to “shrink” the horizon Moon on command?

Yes. Some people find that looking at the Moon upside down (bending forward and looking through their legs) or viewing it through a camera lens eliminates the contextual cues. The Moon can suddenly appear smaller because your brain no longer applies the same distance references.

Does the color of the Moon near the horizon affect how big it looks?

While the reddish or yellowish color near the horizon can make the Moon stand out more, the color itself doesn’t directly change perceived size. However, when something is bright or uniquely colored, our attention and emotional response might amplify the illusion.

Is there any actual difference in brightness or clarity?

The Moon can appear dimmer near the horizon because you’re looking at it through more atmosphere, which scatters light. But this doesn’t affect how large it looks. In fact, the contrast between a slightly dimmer Moon and the horizon backdrop can sometimes make it seem more dramatic.

Do other celestial objects show a similar illusion?

Yes, the Sun also appears larger at sunrise and sunset for the same psychological reasons. In certain circumstances, even large constellations or planets near the horizon can look more imposing, though the effect is most noticeable with the Moon and Sun because they have more substantial apparent diameters.

Myth-Busting

Myth: “The Moon really is bigger on the horizon.”

Reality: The Moon’s actual angular size in the sky doesn’t change enough to account for what we see. It’s the same Moon, same distance. The difference is perception.

Myth: “Atmospheric lensing significantly enlarges the Moon at the horizon.”

Reality: Refraction is mild and mostly noticeable as a flattening or slight distortion, not a big magnification. The human brain, not the atmosphere, is the main reason for the Moon Illusion.

Myth: “If you measure the Moon with your finger near the horizon vs. overhead, it’ll be bigger.”

Reality: Try it! Hold out a ruler or use your thumb’s width. You’ll see no significant difference in how many millimeters cover the Moon’s disk. Any small change is overshadowed by the psychological “wow factor.”

How to See It in Action

- Watch the Rising Moon: Pick a night when the Moon is full or nearly full, and watch it ascend over a distant landscape. Note how large it appears.

- Wait an Hour: As it rises higher, notice how it “shrinks.”

- Use a Reference: Cover the Moon with a small object at arm’s length, both near the horizon and again overhead. Observe how the coverage needed doesn’t really change.

This hands-on approach often solidifies the concept that the Moon Illusion is mostly in your mind’s eye.

Atmospheric Effects: A Side Note

Though the primary cause of the horizon Moon’s bigness is psychological, the atmosphere can add a dash of drama:

- Scattering of short-wavelength light (the reason sunsets are red) can give the Moon a reddish hue near the horizon.

- Refraction can create a slight oval shape.

- Haze or humidity might diffuse the Moon’s brightness.

These factors can enhance the “wow” factor but do not account for the large difference in perceived diameter.

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings

In many cultures, a large low-hanging Moon is viewed as mysterious or magical, giving rise to harvest festivals or romantic imagery. Sometimes, these cultural beliefs reinforce the idea that the Moon actually changes size, embedding the illusion deeper into collective consciousness.

Folklore might claim the big orange Moon on the horizon signals a change in weather or a time for planting. Though these can be endearing tales, they don’t hold scientific weight. The Moon’s color and apparent size simply coincide with certain atmospheric conditions and the vantage point at the horizon.

Step-by-Step Breakdown

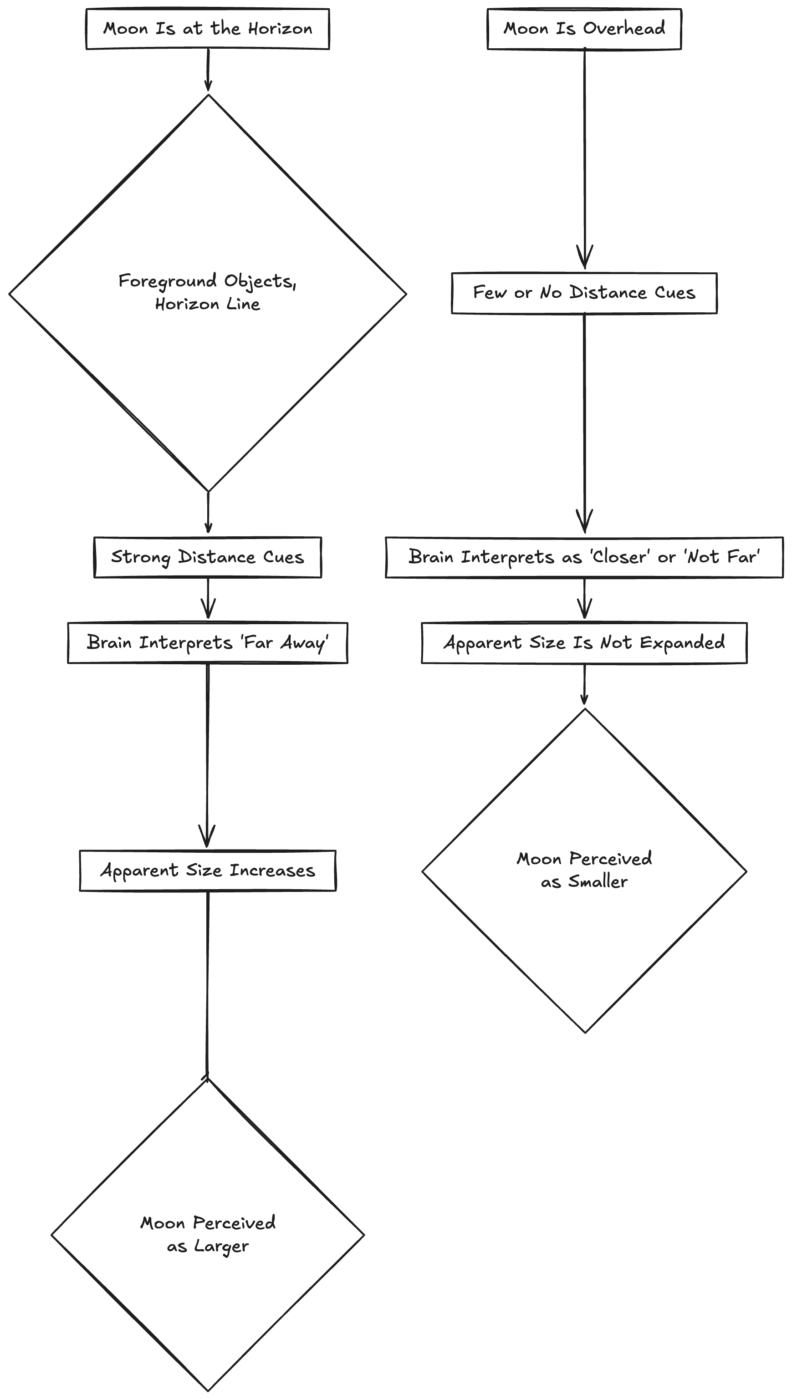

Below is a flowchart capturing the main reasons for the Moon Illusion:

Diagram: Why the Horizon Moon Looks Bigger

- When the Moon is at the horizon (A), we see it near foreground objects or a distinct horizon line (B).

- Our brain registers strong distance cues (C), concluding the Moon is “far away” (D).

- This leads to an increased apparent size (E), making the Moon “seem bigger” (F).

- Overhead (G), we lack strong reference points (H).

- Our brain sees the Moon as not far away (I), and doesn’t enlarge it in our perception (J).

- So we think it’s “smaller” (K), even though its actual angular size is essentially the same.

A Word on Optical Illusions

Optical illusions highlight the flexibility and complexity of human vision. We’re constantly integrating numerous cues—shadows, perspective lines, relative sizes, emotional emphasis—into a cohesive image of the world. Sometimes, these cues conflict or lead to surprising interpretations. The Moon Illusion is a wonderful testament to how vision isn’t a perfect reflection of reality, but rather a skilled interpretation by our brains.

Scientific Consensus

Most astronomers, psychologists, and vision scientists agree that no single factor perfectly explains the phenomenon. Instead, it arises from multiple influences:

- Depth cues: The horizon is perceived as farther away.

- Relative size: Comparing the Moon to known objects (trees, buildings).

- Cognitive illusions: Ponzo, Ebbinghaus, and other illusions that trick our size perception.

- Slight atmospheric effects: Refraction, color changes, or haze that can accentuate the illusion.

While debates persist about the exact contributions of each component, the general consensus remains that psychological factors are the primary drivers.

Final Takeaways

- The Moon’s actual size doesn’t balloon or shrink as it traverses the sky.

- The effect is strongly tied to perception—our brains interpret the Moon differently depending on contextual cues.

- Simple experiments (like comparing the Moon to a coin at arm’s length) confirm that its angular diameter stays roughly constant.

- Atmospheric lensing is minor and cannot explain the robust illusions we see.

- This phenomenon reveals how powerful and, at times, misleading our visual interpretation of distance and size can be.

FAQ

Does the Supermoon make this illusion stronger?

During a Supermoon—when the Moon is slightly closer to Earth (perigee)—its actual angular size is larger by a small percentage (around 7% to 14% compared to a typical Full Moon). This can slightly enhance the horizon illusion, but the biggest factor remains our psychological perception.

Will taking a photograph show the larger Moon near the horizon?

Usually, photographs show the Moon’s true angular size, which can look disappointingly small. Our eyes and brains ramp up the illusion, but a camera lens lacks that psychological context. If you want the photo to match what your eyes see, you might use a telephoto lens, but that’s artificially magnifying the image.

Can the Moon Illusion happen at other moon phases?

Yes, the Moon Illusion can occur during any phase, though we most commonly notice it when it’s full or nearly full, as the disk is brighter and more striking near the horizon. You can observe a larger crescent Moon at the horizon too, just not as dramatically as a full one.

Does Earth’s curvature matter?

Earth’s curvature affects the distance to the horizon, but that’s not the main driver of the Moon Illusion. Whether you’re on a high mountain or at sea level, the phenomenon persists.

Can children or animals see the Moon Illusion?

Children do perceive a larger Moon at the horizon, though their explanations might be more imaginative. As for animals, it’s less clear whether they have the same illusions, since illusions rely on interpretations rooted in visual psychology and conceptual distance cues. Without language or abstract spatial reasoning, animals likely don’t experience the same phenomenon in the same way.

Myth-Busting: Do Our Eyes Change Focus?

Some suppose that eye focus or lens shape might be different when looking at the horizon vs. overhead. While focusing distance can shift slightly, experiments show that those changes don’t cause the large effect we see. The crux of the phenomenon lies in mind-set rather than eye-set.

Relatable Comparison: Car Headlights on a Highway

Imagine driving on a dark highway at night and seeing oncoming headlights in the distance. They can appear smaller or dimmer at first, then bigger as you draw near. Even though the actual intensity of the headlights doesn’t change much, your context—knowing you’re approaching a car—makes them seem brighter and larger. Similarly, the horizon fosters the impression that the Moon is further away, thus we perceive it as bigger to make “visual sense” of the environment.

Understanding Our Cosmic Perspective

Being mindful of how we perceive the Moon and sky can deepen our appreciation of both astronomy and psychology. Each time you see that looming, enormous Moon climbing above the rooftops, you can marvel at the subtle interplay between celestial mechanics and the human brain.

Read more

- The Moon Illusion by Maurice Hershenson.

- An insightful deep dive that explores various experiments and theories explaining why the Moon Illusion fools us so effectively.

- Foundations of Vision by Brian Wandell.

- An authoritative resource on how human vision and perception works, shedding light on illusions like the one we see with the Moon.

- Visual Intelligence: How We Create What We See by Donald D. Hoffman.

- Investigates the science behind our visual system and how our brains construct our reality, including instances of deceptive perception.

Each of these books delves deeper into the psychological and neurological mechanics that enable illusions like the Moon Illusion, blending fascinating experiments with robust theories of human perception.