TL;DR: Water transforms into a solid (ice) when temperature drops low enough for its molecules to arrange in a stable crystalline pattern.

Why Water Turns Solid

Water freezing is more than just a chilly inconvenience—it’s a glimpse into the deeper physics and chemistry of our world. When you place liquid water in a freezer or leave it outside on a frigid day, you trigger a fundamental transformation in the molecular behavior of H₂O.

All substances can exist in different phases: solid, liquid, or gas. But water stands out because it has unique hydrogen bonds—tiny, attractive forces between molecules that become especially important when temperatures approach freezing. At high temperatures, water’s molecules zip around too fast to form a rigid network. As they cool down, they slow, and these hydrogen bonds lock them into place, creating the familiar lattice of ice.

It’s helpful to visualize these molecules as energetic dancers, moving freely in the warmth. As the music (heat) fades, their movements slow, and they gather into an orderly formation, “holding hands” with their neighbors. The result is water in its solid state: ice.

The Science Behind Freezing Temperatures

While you’ve probably heard that 0°C (32°F) is water’s freezing point, that statement glosses over fascinating details. The precise moment water freezes depends on factors like pressure, impurities, and even the presence of surfaces where ice can begin to form (called nucleation sites). Under standard atmospheric pressure—roughly 101.3 kilopascals (14.7 psi)—water transitions into ice around 0°C. Yet in reality, the process can start slightly above or below that temperature if conditions are just right.

Thermodynamic Stability

We can think of water freezing as nature’s quest for energetic stability. Molecules in ice are more organized; they form a stable, crystalline arrangement that requires less energy to maintain at low temperatures. When water is above 0°C, the jostling of molecules is simply too energetic to allow a fully frozen lattice to persist. But once the heat content decreases, the system “finds” a lower-energy configuration: solid ice.

A Snapshot of Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding is a special kind of attraction that arises because the water molecule has a partially positive side (near the hydrogen atoms) and a partially negative side (near the oxygen atom). These slight electrical charges act like magnets, pulling molecules closer together.

In liquid form, water molecules constantly break and form new hydrogen bonds, leading to fluid movement. In ice, most hydrogen bonds remain intact, creating a more fixed shape. This fixed shape is why ice has a hexagonal structure, which is also why snowflakes always exhibit six-fold symmetry.

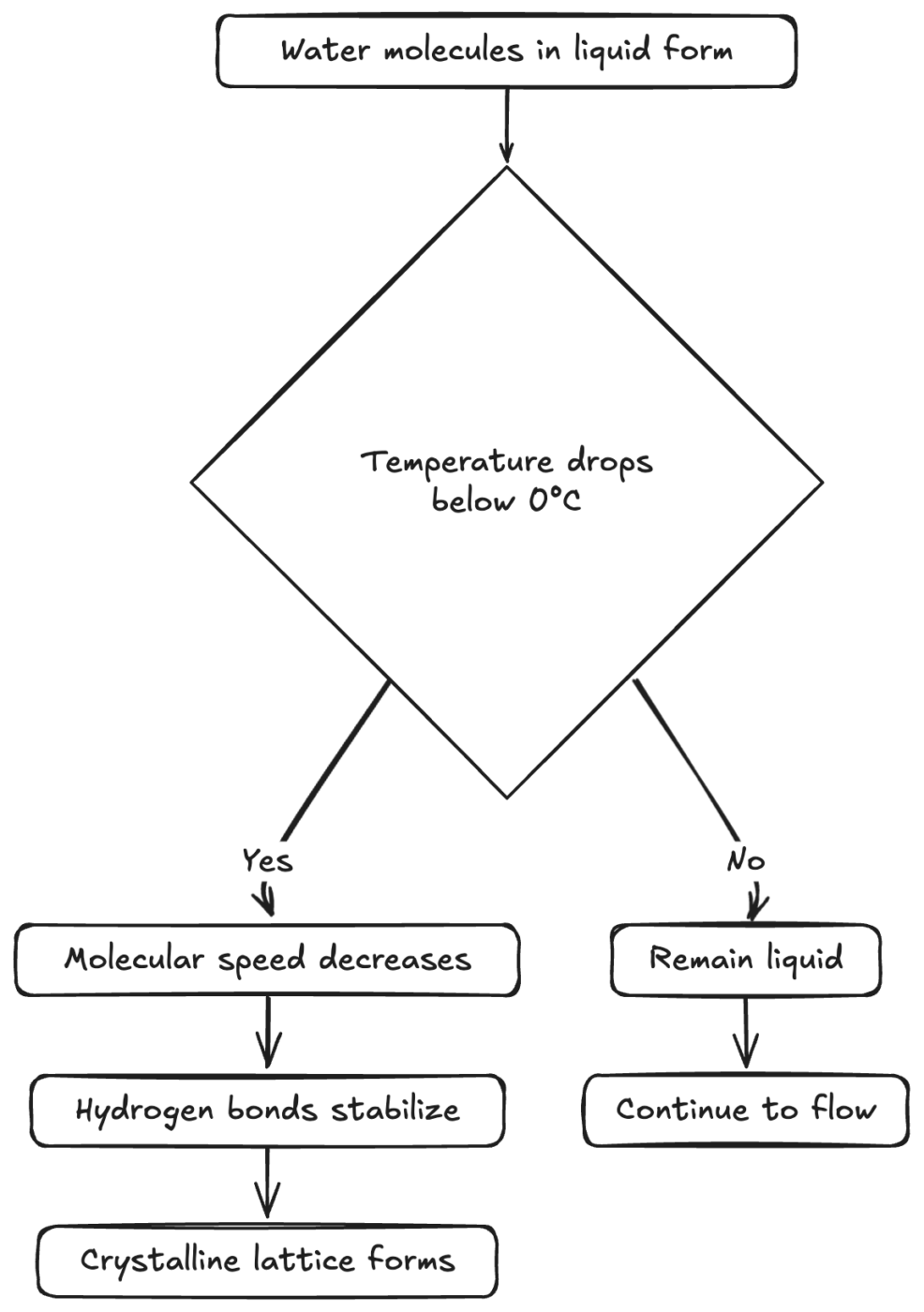

Visualizing the Freezing Process

Below is a simplified diagram showing how water molecules respond to dropping temperatures, ultimately forming ice crystals.

Diagram: The Path to Freezing

As you can see, the critical threshold is around 0°C under normal conditions. Below this point, water molecules have less kinetic energy and are able to lock into a crystalline arrangement.

How Energy Moves During Freezing

Even though water’s temperature drops as it approaches freezing, there’s an intriguing plateau in the cooling process known as the latent heat of fusion. This phenomenon describes the energy required to change water from liquid to solid without further lowering the temperature. In practical terms, you might see a glass of water sit at about 0°C for quite a while before finally turning into ice.

That pause is the water shedding its latent heat. Only after enough heat energy is released can the water fully transition to ice. This explains why lakes and ponds don’t instantly freeze in winter—they must first lose a massive amount of heat to the surrounding environment.

The Role of Pressure and Impurities

Pressure Matters

Water’s freezing point can shift under high-pressure or low-pressure conditions. If you increase the pressure significantly, ice can actually melt instead of freeze, depending on the ice “phase” you’re dealing with (ice can have multiple crystalline forms, each stable under different temperature and pressure conditions). This leads to fascinating phenomena like ice skating, where the pressure from your skate’s blade slightly melts the ice, creating a thin layer of water that reduces friction.

Impurities and Freezing Point Depression

Dissolved substances—such as salt—lower water’s freezing point, a process known as freezing point depression. This is why sidewalks are salted in winter. The presence of salt disrupts the formation of a stable ice lattice, effectively keeping liquid water at temperatures below 0°C. As a result, salted roads and walkways remain slushy rather than icing over.

Comparing Water to Other Liquids

Not all liquids freeze at 0°C. Ethanol, for example, stays liquid down to about -114°C (-173°F). Liquid mercury doesn’t freeze until around -39°C (-38°F). The reason water has a relatively high freezing point is tied to the strength of its hydrogen bonds. Without them, water would freeze at a much lower temperature and boil at a much lower temperature, drastically changing the climate and life on Earth as we know it.

Supercooling: Water Below 0°C That Stays Liquid

You may have seen mesmerizing videos where someone takes a bottle of purified water out of the freezer, gives it a quick tap, and the water instantly freezes before your eyes. This phenomenon is supercooling. Water can remain in a liquid state below 0°C if there are no nucleation sites for ice crystals to form and if the water is extremely pure.

When a disturbance—like tapping the bottle—creates a starting point for crystal growth, ice rapidly propagates through the supercooled liquid. Think of it as a domino effect: once one crystal forms, the rest follow suit in a chain reaction.

How Water’s Density Changes

Unlike most substances, water expands upon freezing. In liquid form, water is densest at about 4°C (39°F). Below this temperature, as water approaches the formation of ice, the molecular arrangement creates spaces between molecules, making ice less dense than liquid water.

This expansion is why icebergs float and why a bottle of water left in the freezer might burst. It also has crucial ecological implications, ensuring that lakes freeze from the top down. Fish and other aquatic life can survive under the ice layer because the denser, slightly warmer water stays beneath.

Why Water’s Solid State Is So Special

Water ice is more than just “solid water.” It’s a crystalline wonder that helps moderate our planet’s climate, shapes geological processes, and influences weather patterns. Our world is teeming with water-based life, partly because ice forms a protective layer on lakes and oceans, reducing further heat loss.

If Earth were the size of a basketball, you could think of its water—liquid and frozen—as a thin shell of paint on its surface. Despite this small fraction, ice caps and glaciers reflect sunlight, helping regulate global temperatures. The fact that water freezes near a temperature comfortable for life (0°C) is one of the many remarkable coincidences that make Earth habitable.

The Journey of Heat Transfer

To understand why water freezes in a specific environment, think about heat transfer—the movement of thermal energy between systems. Heat can move via:

- Conduction: Direct contact between objects.

- Convection: Circulating currents in fluids like air or water.

- Radiation: Transfer of heat through electromagnetic waves, such as infrared radiation from the Sun or even your body.

When you place water in a cold environment (like a freezer), heat flows from the water to the colder surroundings. Once enough energy leaves, the water’s internal temperature plummets to the point where the molecules can no longer move freely, forming ice.

Connections to Everyday Life

You probably deal with freezing water all the time:

- Ice cubes in a drink.

- Frost on a window.

- A frozen lake in winter.

- An ice pack for injuries.

In each case, the fundamental science remains the same: slow the molecular motion enough, and those molecules crystallize. The difference is mainly how quickly the environment removes heat. An ice cube in a freezer, for example, forms faster if you place it in direct contact with a cold metal tray rather than a plastic one—metal conducts heat away more quickly, speeding up the freezing process.

Molecular Arrangements in Ice

Scientists have identified at least 17 different crystal forms (or polymorphs) of water ice, labeled ice I, ice II, ice III, and so on. The ice in your freezer is ice Iᵕ (pronounced “ice I-h”), which has the classic hexagonal structure. Under extreme pressures and super-cold temperatures, you can get exotic forms like ice II or ice VIII, each with a different arrangement of molecules. These forms mostly exist in laboratory conditions or in extreme planetary environments, such as on the moons of Jupiter or Saturn.

The Freezing Process in Nature

Lakes and Rivers

In colder climates, you’ll notice that ice develops on the surface of lakes, not the bottom. Because water reaches maximum density at 4°C, it sinks below the cooler water that is approaching 0°C at the surface. Eventually, the topmost layer freezes, forming an insulating layer that slows further cooling of the water below.

Oceans

Ocean water has a high salt content, which lowers the freezing point to around -1.8°C (28.8°F). Because of its saltiness, ocean ice forms more slowly, and its texture can be quite different from freshwater ice. Polar seas experience large expanses of sea ice, crucial to marine ecosystems and Earth’s climate.

Atmosphere

Water in the atmosphere can freeze as well, forming snow and hail. Snow forms when ice crystals gather around tiny particles of dust or other aerosols. Hail requires more turbulent conditions inside storm clouds. Each scenario hinges on temperature drops and the availability of nucleation sites.

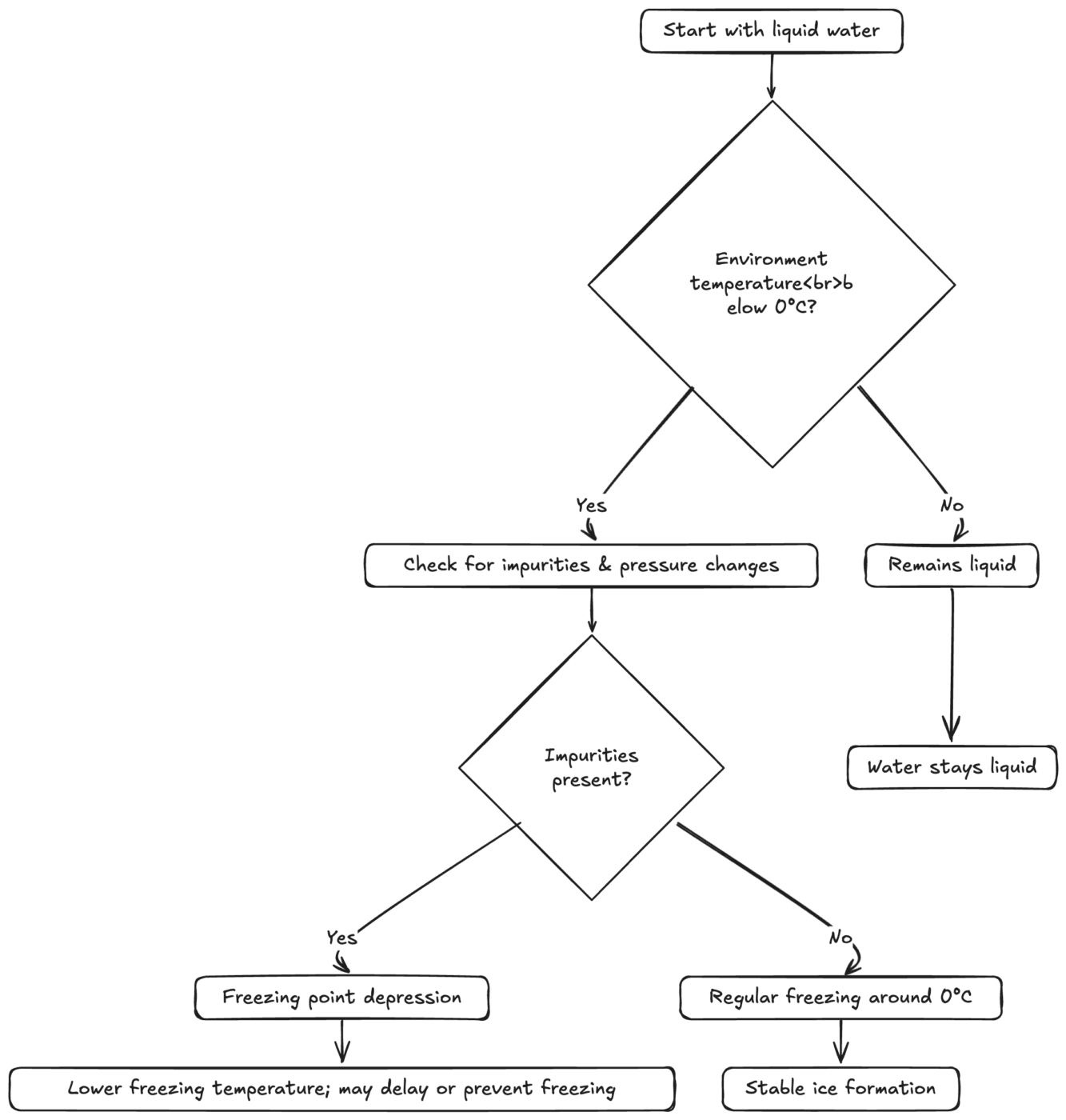

Diagram of Freezing Pathways

The freezing process can vary depending on temperature, impurities, and pressure. Here’s a simplified look at some branching possibilities:

Diagram: Various Pathways Toward Ice Formation

From this, you can see how different factors—temperature, impurities, and pressure—all interact in determining if and when water solidifies.

Myth-Busting: Common Misconceptions About Freezing

Myth #1: Hot Water Always Freezes Faster Than Cold Water

This idea is known as the Mpemba effect, stemming from experiments where hot water sometimes appears to freeze faster than cold water under specific conditions. While intriguing, it’s not as simple as saying “hot water freezes faster.” Differences in evaporation, convection currents, or container shape might cause hot water to lose heat in unexpected ways. Scientific consensus holds that if every variable is controlled, cold water generally freezes sooner because it has less energy to lose.

Myth #2: Distilled Water Doesn’t Freeze

Distilled or pure water definitely can freeze. It just might need a nucleation site—a surface or impurity around which ice can form. In extreme purity conditions, water may supercool below 0°C before crystallizing. The freeze will still occur; it just requires the right trigger.

Myth #3: Freezing Kills All Bacteria

While freezing can slow bacterial growth drastically, it doesn’t always kill all microorganisms. Some bacteria can survive at low temperatures, remaining dormant until conditions warm up again. This is why frozen food can still spoil if not handled properly after thawing.

Real-Life Examples of Freezing Phenomena

Making Ice Cream

Ice cream production leverages the latent heat concept to create a creamy texture. By lowering the mixture’s temperature rapidly—often using salt on ice to achieve temperatures below 0°C—small ice crystals form, preventing a grainy mouthfeel. This approach harnesses freezing point depression to pull heat from the ice cream mix more efficiently.

Freezing Rains and Black Ice

Sometimes rain droplets fall through a subfreezing layer of air just above the ground. The drops become supercooled, freezing upon contact with roads and sidewalks. This is how black ice forms—an often-invisible sheet of ice that poses a hazard to drivers and pedestrians alike.

Frost Formation on Windows

On a frosty morning, you might see intricate crystal patterns on your car’s windshield. These patterns are the result of water vapor in the air coming into contact with a supercooled surface, turning directly into ice crystals in a process known as deposition. Small dust particles or scratches on the glass can act as nucleation sites, leading to gorgeous symmetric designs.

Water’s Freezing in the Cosmos

Water freezing isn’t limited to Earth. Throughout the solar system and beyond, water ice is found on moons, comets, and even in interstellar clouds. For example, Jupiter’s moon Europa is believed to harbor a subsurface ocean beneath a thick crust of ice. Understanding freezing processes on celestial bodies can offer clues about possible extraterrestrial life and the history of water in space.

Why 0°C Is Crucial for Life

On Earth, the threshold of 0°C is more than a random benchmark. This temperature shapes our climate and ecosystems in fundamental ways. Because ice is less dense, it floats, insulating bodies of water so marine organisms can survive in cold regions. Seasonal freezing and thawing also affect nutrient cycles, animal migration, and agriculture.

If the freezing point of water were significantly lower, Earth’s climate dynamics would shift dramatically. Polar caps might not form in the same way, affecting global temperature regulation. In essence, water’s behavior at freezing is a cornerstone of the planet’s habitability.

Real-World Applications

Cryopreservation

In cryopreservation, cells, tissues, and even organs are stored at ultra-low temperatures to keep them viable for future use. The challenge is to prevent ice crystals from damaging delicate cell structures. Researchers often use special solutions called cryoprotectants to inhibit large crystal formation, which can puncture cell membranes.

Industrial Cooling

Large industrial processes—like those in power plants—require massive cooling systems. Water that transitions to ice can absorb huge amounts of heat (the latent heat of fusion), so some systems take advantage of this phase change to regulate temperatures. When the temperature rises, the stored ice melts, absorbing heat.

Food Preservation

Beyond the home freezer, the global food industry relies on freezing technology to preserve a wide range of products. Freezing slows enzymatic reactions and microbial growth, extending shelf life. Flash-freezing techniques can create smaller ice crystals, preserving the texture and quality of fruits, vegetables, and meats.

The Physics of Crystals

At the heart of water’s freezing process is the broader physics of crystallization. This process occurs whenever molecules or atoms settle into a repeating, orderly pattern. Substances ranging from metals to salts to certain polymers all undergo crystallization under the right conditions. Water happens to be one of the most common and vital examples, touching every facet of life and environment on Earth.

Energy, Entropy, and Order

From a broad physics standpoint, you might wonder: “Why would nature choose an ordered solid over a more disordered liquid, especially when the universe tends toward disorder, also known as entropy?”

The answer lies in how energy and entropy balance each other at different temperatures. At higher temperatures, the gain in entropy (disorder) from staying liquid is favorable. But as temperature drops, the system can reduce its overall energy by forming a tightly bonded crystal, and that energy saving outweighs the entropy cost of becoming more ordered. This is the essence of thermodynamics in freezing.

The Role of Air and Evaporation

When water evaporates, it requires a significant amount of energy to transition from liquid to gas, called the latent heat of vaporization. This effect can cool the water left behind, occasionally helping it reach freezing temperatures faster if conditions allow for rapid evaporation. That’s part of why some people see the Mpemba effect—hot water might evaporate more quickly, losing mass, and therefore has less total heat content to shed overall.

FAQ Section

Does pure water always freeze at 0°C?

It usually does under normal pressure conditions, but supercooled water can stay liquid below 0°C if it lacks nucleation sites. Once a crystal forms, the freezing process becomes almost instantaneous.

Why does ice float?

Ice is less dense than liquid water due to the open lattice structure formed by hydrogen bonds. This extra space between molecules increases the volume while lowering the mass density, causing ice to float.

Can water freeze instantly?

In rare cases, supercooled water may appear to freeze instantly when disturbed. The reality is that once the first ice crystal forms, the rest of the liquid quickly follows suit in a chain reaction.

What about saltwater or sugary solutions?

Both salt and sugar can lower water’s freezing point, making it harder to form ice at 0°C. This phenomenon is used in cooking, ice cream making, and de-icing roads in winter.

Why do freezing pipes burst?

As water inside a pipe freezes, it expands. Since ice takes up more volume than the same mass of liquid water, the pressure inside the pipe can become enormous, causing the pipe to crack or burst.

Is the freezing process reversible?

Yes. Once ice warms above 0°C (under normal pressure), it melts back into liquid water. The transition is reversible as long as you stay within water’s stable temperature and pressure ranges.

Does boiling water freeze faster than cold water?

Not generally. Under typical, controlled conditions, cold water freezes faster because it has less heat energy to lose. The Mpemba effect is context-dependent and not a universal rule.

How do I avoid large ice crystals when freezing food?

Use rapid freezing methods (such as placing items in the coldest part of the freezer) so that water in the food forms smaller crystals, preserving texture and flavor.

Read More

For those fascinated by the interplay of temperature, physics, and everyday life, the following books and references offer deeper insights:

- Stuff Matters by Mark Miodownik

- The Disappearing Spoon by Sam Kean

- Markus Buehler’s Research Publications on material science and protein crystallization

- NOAA Water Science Resources detailing freezing phenomena in Earth’s water systems

Understanding why water freezes not only enriches your appreciation for everyday phenomena—like ice in your drink or snow on your windowsill—but also opens a window into the deeper principles governing our planet. Whether it’s the mesmerizing structure of snowflakes or the thick ice sheets at the poles, the freezing of water is a foundational process that keeps our world thriving.