TL;DR: Woodpeckers protect their brains using unique skeletal adaptations, tight muscles, and efficient shock absorption mechanisms that prevent headaches or injury despite rapid, repeated pecking.

Astonishing Impact: Woodpeckers and Their Head-Banging Feats

When a woodpecker hammers away at tree bark, it experiences deceleration forces up to 1,000 g—far more than what astronauts feel during rocket launches. Yet these birds carry on, peck after peck, without showing signs of headache or brain damage. How is that possible?

They have a variety of natural design tweaks that act like built-in shock absorbers. Their special skull bones, beak structure, and thick neck muscles distribute and cushion the forces. Understanding these adaptations helps explain how they can do repetitive, high-speed drilling all day long with no apparent ill effects.

How Fast and Forceful Is a Woodpecker’s Peck?

A woodpecker can strike the wood at up to 20 pecks per second, with each peck lasting only a few milliseconds. This quick, forceful motion is roughly equivalent to a person smashing their face into a tree trunk thousands of times a day—an unimaginable feat for humans, but ordinary life for woodpeckers.

Pecking Rates and Energy

Woodpeckers are not just lightly tapping. Many species can generate around 600-700 g of force—some might reach close to 1,000 g in short bursts. For comparison, in a car crash, humans typically sustain injuries at around 50-100 g if unprotected. The difference is that woodpeckers are built to handle these frequent “crashes” with minimal harm.

The Key Adaptations Protecting Woodpecker Brains

1. Specialized Skull Structure

Woodpeckers have a thick skull with dense but slightly spongy bone at key points. Unlike typical birds, they have:

- Trabecular (spongy) bone arranged in a tight mesh that absorbs shock.

- A short cranium that leaves less room for the brain to rattle around.

- Reinforced frontal bones that help dissipate impact forces outward, preventing too much direct energy transfer to the brain tissue.

In simpler terms, picture an advanced helmet that’s stiff in some areas and cushiony in others. It’s precisely engineered for regular collisions.

2. The Hyoid Apparatus: A Built-In Safety Belt

The hyoid bone is a remarkable structure that starts at the tongue, wraps around the head, and anchors near the nostrils or eyes. This bony/tendinous loop in a woodpecker can act like a seatbelt for the skull:

- Wraps around the back of the skull, helping distribute loads.

- Provides additional support so the bird’s head doesn’t whip back violently on impact.

- Some woodpeckers have hyoid extensions that cradle the skull almost like hooking around the entire cranium, further stabilizing the head-neck connection.

3. Beak Design for Impact Distribution

Woodpecker beaks are not uniform in density. The outer layer (rhamphotheca) is relatively stiff, while the inner structure has a bit more flex. This graded stiffness means the beak can absorb some of the force on initial contact. Additionally:

- The upper beak is usually slightly longer than the lower beak, guiding forces away from the brain.

- Micro-adjustments in the beak’s shape help channel force around, rather than into, the cranium.

4. Tight Neck Muscles

The neck muscles in woodpeckers are super strong and highly coordinated. These muscles:

- Keep the head aligned just before impact, reducing twisting or bending that might cause injury.

- Provide a rigid but controlled posture.

- Counterbalance each strike so that the bird’s body and head move as one integrated system.

Imagine a well-trained boxer bracing for a punch—the woodpecker’s neck does something similar but at lightning speed, every peck.

5. Small, Lightweight Brain

While a woodpecker’s brain is proportionally large for a bird, it’s still relatively small and is packed tightly within the skull. A smaller mass experiences lower inertia, meaning it moves less within the skull on impact. If Earth were the size of a basketball, the woodpecker’s brain might be the size of a pea inside that ball—tiny but snug, limiting harmful movement.

Diagram Explanation: The beak (A) first encounters the impact. Force is redirected (C) through dense skull bones (D) and further stabilized by the hyoid apparatus (E). The small, snug brain (G) minimizes harmful shifting, resulting in minimal or no brain injury (I).

Is There Really No Headache Risk?

Studies on Brain Damage

Researchers have dissected woodpecker specimens and found relatively few signs of trauma in the brain. Older studies speculated that maybe they did get mild trauma over a lifetime, but newer imaging suggests they are largely protected. More recent data even hint that some proteins associated with brain injury (such as tau proteins) might accumulate in a woodpecker’s brain, but not to the extent that it causes noticeable functional damage. The consensus is that woodpeckers handle shock far better than we do.

Pressure-Related Factors

Another factor is the cerebrospinal fluid pressure. In woodpeckers, the fluid volume around the brain is limited. With less fluid, the brain has less room to jiggle or bounce against the skull. It’s like having extra padding in the exact right places.

Myth-Busting: Do Woodpeckers Ever Get Concussions?

Myth: Woodpeckers are immune to concussions.

Reality: While it’s rare, severe collisions with unusually hard surfaces—like metal or glass—could pose a risk. However, in their natural habitat (trees), woodpeckers rarely experience enough force to cause a “knockout.” Their specialized anatomy is well-suited to wood, but if a woodpecker repeatedly pecked something extremely rigid, there could be some level of injury risk, though it remains low compared to other birds.

The Role of Behavior and Pecking Technique

Wood Selection

Woodpeckers are picky about which wood to target. They generally peck at:

- Decaying or softer wood for nesting cavities, making it easier to excavate.

- Thinner bark areas to find insects.

- Resonant surfaces for drumming to communicate territory or mating status.

They typically avoid rock-hard surfaces. This behavioral choice further reduces the chance of dangerous shocks.

Hitting the Trunk Squarely

Woodpeckers also prefer to strike with a straight, linear motion. Their body often aligns with the trunk, ensuring the head doesn’t twist or jerk sideways. Minimizing rotational forces is crucial to avoiding injuries that might occur with an off-angle strike.

Evolutionary Insights: A Co-Evolution of Neck, Skull, and Behavior

Gradual Optimization

Over millions of years, woodpeckers’ ancestors that managed to drill effectively without injuring themselves were more successful in feeding and nesting. Their stronger necks, denser skulls, and better beak geometry gave them an edge in survival. It’s a striking example of natural selection shaping a suite of traits that work together seamlessly.

Convergent Evolution in Drilling Birds

Some other birds (like sapsuckers or certain tropical species) also exhibit aspects of this adaptation, though woodpeckers are the best-known example. Not all “drilling” birds are as specialized, but they share certain protective strategies, hinting that strong selection pressures favor shock-absorbing features whenever repeated, high-impact pecking is needed.

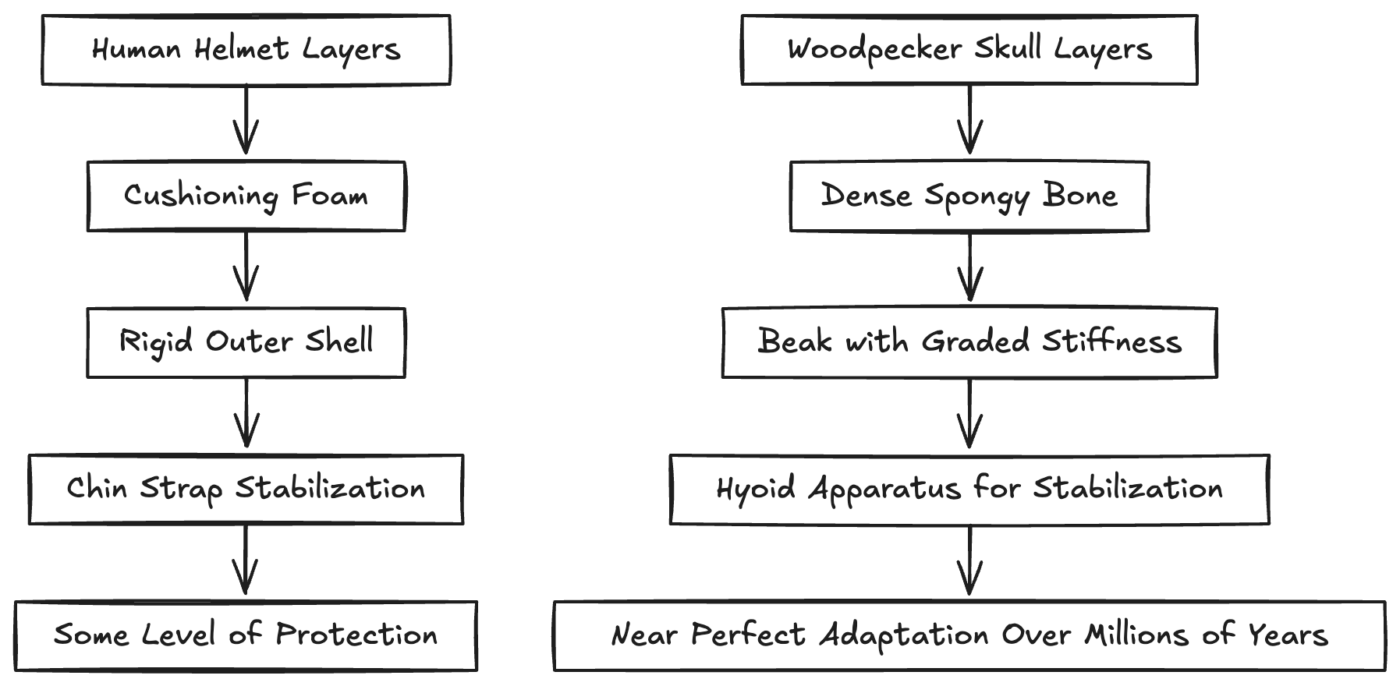

Real-World Comparisons: Human Athletes and Helmets

If a human boxer experienced the same rapid deceleration of a woodpecker’s head, they’d likely suffer severe concussions without protective gear. Helmets in sports like American football or ice hockey try to replicate what a woodpecker’s skull does naturally:

- Padding to distribute shock.

- Rigid shell to prevent direct impact.

- Chin straps to keep the head stable (akin to the hyoid apparatus).

Even with the best helmets, humans remain nowhere near as protected as a woodpecker’s built-in system.

Diagram: Human Helmet vs. Woodpecker Skull

Diagram: Similarities and Differences in Impact Protection

In humans, we rely on artificial layering (A, B, C). Woodpeckers have evolved a biological system (E, F, G, H). Helmets reduce risk (I), but woodpeckers show an even more integrated solution (J).

Common Questions About Woodpeckers

Why do woodpeckers peck in the first place?

They peck for three main reasons:

- Foraging: Drilling into wood to reach insect larvae.

- Nesting: Creating cavities in trees for laying eggs.

- Communication: “Drumming” on resonant surfaces to mark territory or attract a mate.

Do woodpeckers only eat bugs?

Many species primarily eat insects, but some also consume nuts, seeds, and even tree sap. A broad diet helps them survive in various habitats.

Can a woodpecker damage a house?

Yes, sometimes woodpeckers drill into wooden siding or eaves—often seeking bugs or creating a resonant drumming spot. While it’s usually superficial, it can become a nuisance if they persist. Homeowners often use deterrents like reflective tape or special devices to discourage them.

Is there a maximum time they can peck without rest?

Woodpeckers can peck rapidly for short bursts—often a few seconds at a time—but they take breaks between sessions. They typically vary their tapping speed and intensity based on the hardness of the wood and the purpose of pecking.

Are woodpeckers found worldwide?

They occur on most continents except Australia and Antarctica. Different species have adapted to forests, woodlands, deserts, and even urban areas, as long as they find suitable trees or structures.

Does a Woodpecker’s Brain Move at All?

Minimal Motion

Even though some minute internal movement might happen, it’s drastically less than what a human would experience under similar forces. The snug fit and spongy bone create a near-zero slack environment inside the skull.

Protective Fluid Dynamics

A small layer of cerebrospinal fluid still exists, but it’s fine-tuned to the bird’s constant pecking activity. Instead of a large fluid cushion that could cause the brain to slosh, woodpeckers have just enough to keep the tissue nourished without giving it much room to jolt around.

The Fascinating Hyoid Apparatus in Detail

The hyoid is an arc-shaped bone that typically supports the tongue in vertebrates. In woodpeckers:

- It extends from the mouth cavity, loops up around the base of the skull, sometimes ending near the orbital region (around the eyes).

- Some species have the tips of the hyoid near the nasal opening; others even have it hooking near the nape.

- This unusual length and route provide mechanical reinforcement that can absorb shock.

Think of it like a built-in safety harness—keeping everything aligned during high-impact moments.

Behavioral Intelligence: Pecking with Precision

Beyond anatomy, woodpeckers also use precision:

- They angle each strike so that the force is channeled primarily along the axis of the neck.

- They momentarily close their eyes just before contact to protect them from flying debris (and possibly reduce jarring).

- They adjust pecking velocity based on the hardness of the wood, so they don’t overdo force beyond what their body can handle.

All these behaviors supplement their physical adaptations, ensuring minimal stress on the brain.

Are There Limits to This Adaptation?

Even with these features, woodpeckers do have thresholds. Extreme scenarios—like repeated, forceful impacts on metal—may cause micro-stresses. Yet in the typical forest environment, the tree trunk’s density matches well with the woodpecker’s capabilities.

Myth-Busting: “They Never Feel Any Discomfort”

Myth: Woodpeckers never feel pain or discomfort.

Reality: While they likely don’t experience constant headaches, they have nerves and can feel pain if injured. Their adaptations prevent serious trauma, but if a woodpecker has an underlying health issue or if it collides with a glass window at high speed, it can be hurt like any bird. They’re simply far more resilient against repetitive pecking forces than other species.

Could Humans Learn from Woodpeckers to Prevent Concussions?

Bio-Inspired Technology

Engineers study woodpeckers to design better shock-absorbing materials and helmet technology. By mimicking the layered approach—rigid exteriors with flexible, spongy interiors and specialized bridging—scientists hope to create safer gear for sports and transportation.

Potential for Medical Devices

The idea of a “hyoid-like harness” to stabilize the head in high-impact activities has intrigued some innovators. While a direct replication might be impractical for humans, the concept of distributing force along a broader skeletal route is powerful.

FAQ

Q: Do woodpeckers get headaches?

A: There’s no evidence that woodpeckers suffer headaches like humans do, thanks to their specialized anatomy and shock-absorbing features.

Q: How often do woodpeckers peck each day?

A: It varies by species and season. Some may peck a few hundred times per day, especially during nesting or drumming season, while others may only do intense pecking sessions sporadically.

Q: Are bigger woodpeckers more prone to brain damage?

A: Generally, no. Larger species like the Pileated Woodpecker have proportionally robust adaptations. Their entire skeletal and muscular systems scale up to handle forces in line with their body size.

Q: Do woodpeckers only peck in daylight?

A: Most do. Woodpeckers are diurnal (active during the day). They rest at night, often roosting in tree cavities or similar safe spots.

Q: Why don’t other birds adopt the same approach?

A: Different birds occupy different niches. Woodpeckers evolved these traits specifically for vertical foraging and drumming. Most birds don’t need to drill wood, so they lack the specialized skull and muscle structures.

Summarizing the Science

In short, woodpeckers avoid headaches or brain damage by combining:

- Spongy skull bones that absorb and redirect impact forces.

- A hyoid apparatus acting like an internal seatbelt.

- Carefully graduated beak design that channels shock away from the brain.

- Strong, well-coordinated neck muscles that prevent unnecessary wobble or rotation.

- A compact, snug-fitting brain leaving minimal room for dangerous movement.

These features, refined over countless generations, allow a woodpecker to peck vigorously at tree bark without fear of chronic concussions or neurological damage.

The Marvel of Avian Engineering

Woodpeckers epitomize bio-inspired brilliance—a living demonstration that nature has remarkable solutions for extreme physical challenges. Whether they’re drumming to announce territory or excavating insects, these birds rely on an integrated synergy of anatomical and behavioral strategies. For them, it’s just another day’s work—no headache required.

Read more

- Biomechanics: Structures and Systems by A. A. Biewener.

Offers insights into how organisms like woodpeckers evolve shock-absorbing systems, providing a broader look at functional anatomy in the animal kingdom. - Avian Architecture: How Birds Design, Engineer, and Build by Peter Goodfellow.

Delves into the varied building and drilling methods used by birds, showcasing the remarkable engineering solutions they employ in their daily lives.