**TL;DR: Because Mars lost its protective atmosphere and stable water supply long ago, its surface became too harsh and inhospitable for life as we know it to flourish.

How Mars Lost Its Once-Promising Conditions

Scientists often call Mars the Red Planet, but billions of years ago, it might have been more of a blue-gray sphere. Evidence shows Mars had running water on its surface—rivers and lakes that could have supported microbial life. If you imagine Mars back then, you’d see a planet not too different from a dusty, desert-like Earth.

Yet, fast forward a few billion years and Mars is a frigid desert with a thin, unbreathable atmosphere. The once-flowing rivers are gone, the lakes are dried up, and the surface is blasted by solar radiation. What changed so dramatically? In short, Mars couldn’t hold onto the environmental factors that allow life to flourish—namely, liquid water and a stable atmosphere.

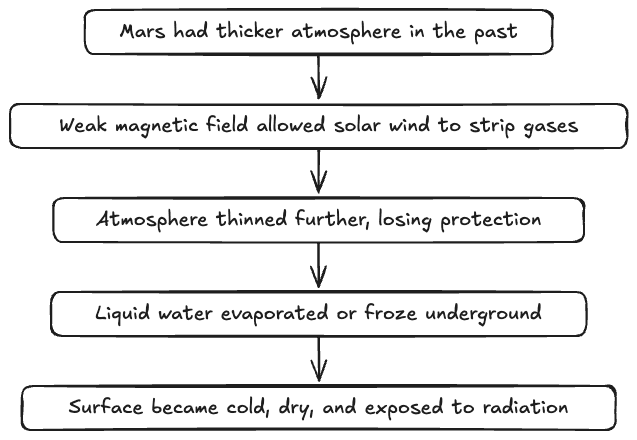

The Importance of a Protective Atmosphere

Every time you step outside on Earth, you’re shielded by a thick envelope of nitrogen, oxygen, and traces of other gases. This protective blanket keeps you safe from harmful radiation while maintaining a comfortable temperature range. Mars, on the other hand, possesses a thin atmosphere composed mostly of carbon dioxide.

Thinness matters because an atmosphere acts like a thermal jacket. Mars’s “jacket” is so light and hole-ridden that it can’t retain enough heat. Daytime temperatures near the equator might get briefly warm, but the heat quickly radiates back into space at night. For life to flourish on a planet’s surface, temperature swings must be relatively mild. On Mars, extreme daily shifts make it challenging for living organisms to survive.

An additional point: a dense atmosphere also helps keep liquid water from evaporating into space. Because Martian air pressure is so low, liquid water readily sublimates (turns from ice to vapor) or evaporates in the near-vacuum conditions. Even if ice melts briefly on a sunny day, it won’t stay liquid for long under current Martian atmospheric pressure.

Diagram: Martian Atmosphere Loss

Diagram: How Mars’s atmosphere dwindled over time, leaving its surface inhospitable

Magnetic Field: Earth’s Invisible Guardian vs. Mars’s Weak Defense

A planet’s magnetic field is like an invisible force field that deflects charged particles streaming from the Sun. Earth’s magnetic field is generated by a molten iron core that’s in constant motion. This field extends far into space, shielding our atmosphere from solar wind erosion.

Mars once had a magnetic field, but it weakened early in the planet’s history, possibly because its core cooled or became geologically inactive. Without this protective bubble, solar particles directly bombarded the Martian atmosphere, “sandblasting” away lighter gases and water vapor. Over eons, Mars lost much of the atmospheric thickness that could have kept its surface warm and wet.

When you lose a magnetic field, you lose a significant layer of protection against cosmic rays and solar wind, both of which can damage or kill living organisms. So if you were to stand on the Martian surface today without a spacesuit, you’d be bathed in higher doses of radiation than on Earth—certainly not conducive to thriving life.

Water: The Lifeblood That Vanished

On Earth, water is everywhere: oceans, rivers, aquifers, and moist air. On Mars, liquid water is scarce on the surface, mostly locked up as ice at the polar caps or in subsurface reservoirs. There’s strong evidence, including images of dried-up riverbeds and mineral deposits, that Mars was once awash with water.

Water is essential for known life because it dissolves nutrients and chemicals, facilitating biochemical reactions. If life ever started on Mars when water was plentiful, it would have depended on that watery environment to survive. As the planet dried up, any potential microbes would face desiccation and freezing temperatures. Imagine placing a houseplant in a sealed vacuum chamber—without water, it quickly withers.

A Once-Milder Climate and the Faded Greenhouse Effect

For a planet to maintain liquid water, it needs not just water itself but the right range of surface temperatures. Earth uses its thick atmosphere to trap heat via the greenhouse effect, a process by which certain gases (like carbon dioxide and water vapor) hold in warmth. Mars does have carbon dioxide, but in amounts too small and too poorly retained to keep the planet warm.

When Mars was young, scientists believe volcanic activity spewed massive amounts of gas into the atmosphere, which helped trap heat. Over time, as volcanoes became inactive and the atmosphere drifted off into space, the greenhouse effect collapsed. Today, temperatures on Mars can plunge below -100°C at night in many regions, a setting harsh for liquid water or typical Earth-based life.

Analogy: The Leaky Greenhouse

Think of Mars’s atmosphere as a greenhouse with broken windows. Sure, there’s some carbon dioxide inside, but the structure is too compromised to keep the heat in. Even if you tried to run a heater inside this greenhouse, most of the heat would leak out. For robust ecosystems to thrive—like the diversity we see on Earth—you need a greenhouse that works properly. Mars’s structure is simply too damaged.

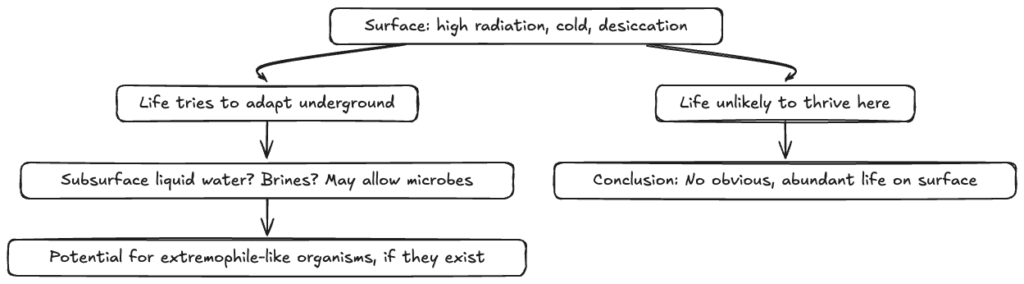

Cosmic Radiation and the Tough Lives of Extremophiles

Earth’s surface is protected by an ozone layer and a magnetic field that filter out UV radiation and cosmic rays. Organisms on Earth also evolved strategies to cope with moderate radiation. On Mars, direct exposure to intense cosmic rays presents a major obstacle.

That said, some organisms on Earth, called extremophiles, thrive in hostile conditions—like deep-sea hydrothermal vents or polar glaciers. Could such hardy microbes survive beneath the Martian surface? Possibly. Scientists suspect pockets of liquid water or brine may lurk below ground, offering refuge from radiation. If Martian life exists today, it’s likely hidden in these shadowy subsurface niches, not teeming on the surface in lush ecosystems as we once imagined.

Diagram: Possible Martian Life Pathways

Diagram: How environmental barriers funnel any hypothetical Martian life into subsurface refuges

Soil Chemistry: Toxic Perchlorates and Harsh Salts

Mars’s soil isn’t just ordinary dirt. It contains high concentrations of perchlorates, chemical compounds that can be toxic to many terrestrial life forms. Perchlorates can wreak havoc on cellular processes, although certain microbes can use them as an energy source under specialized conditions.

For human explorers or typical Earth-based organisms, these chemicals present serious hurdles. You’d need thorough filtration or protective measures to avoid contamination. This chemical hostility in the soil further explains why we don’t see fields of Mars plants or thriving bacterial colonies on the surface.

The Temperamental Climate

Even if we ignore the thin atmosphere, radiation, and soil chemistry, Mars experiences wild seasonal variations. The planet’s eccentric orbit and tilt cause temperature extremes from equator to pole. Dust storms regularly sweep across the planet, sometimes enveloping it entirely. These storms can last for weeks or months, blocking sunlight and dropping temperatures. For photosynthetic life forms, that’s a massive challenge—imagine living under a perpetual dust cloud that denies you energy from the Sun.

Compared to Earth’s stable climate cycles, Mars’s environment is more like an unpredictable roller coaster. Without a robust atmosphere to buffer changes, life forms need extraordinary adaptations to endure such extremes.

Myth-Busting: Mars as a “Dying” Planet

Myth: Mars was lush with forests and advanced life that slowly perished

Some early sci-fi stories depicted a dying civilization on Mars. While captivating, the evidence suggests any warm, watery period on Mars was extremely early—billions of years ago—long before advanced life could have evolved to a complex, forested stage.

Reality

Current data points to a planet that had a brief (in geologic terms) window of habitability. If life existed, it was likely microbial and short-lived. There’s no sign of advanced ancient civilizations or massive plant-filled landscapes. The combination of atmospheric loss, drying conditions, and radiation exposure steered Mars away from supporting complex ecosystems.

Searching for Ancient or Buried Martian Life

Despite the harshness, NASA and other space agencies aren’t giving up. Rovers like Perseverance and Curiosity are equipped with sophisticated instruments to hunt for biosignatures—chemical signs that living organisms once existed. They scrutinize rock layers, analyze soil composition, and even collect samples for potential return to Earth in the future.

If Earth were the size of a basketball, Mars would be about the size of a softball—smaller planet, smaller internal heat reservoir, and thus a shorter geologic lifespan for active processes like volcanism and magnetic field generation. This planetary “underdog” status gave Mars less time to nurture life’s development before environmental conditions deteriorated.

The Role of Planetary Size

In the cosmic real estate market, size often determines how well a planet can hold onto its atmosphere and sustain internal geological processes. Mars’s smaller mass means:

- Lower gravity, easier for gases to escape into space.

- Faster cooling of the planet’s interior, leading to a weaker or non-existent magnetic field.

- Reduced volcanic activity over time, meaning less outgassing to replenish the atmosphere.

All these factors accelerate atmospheric loss and hamper the creation of stable, life-friendly conditions. Think of Earth as a large pot that keeps simmering, releasing steam and staying hot, while Mars is a smaller pot that rapidly loses heat and evaporates water.

Could We Terraform Mars?

The idea of terraforming—transforming Mars into a second Earth—fascinates visionaries. The concept usually involves releasing greenhouse gases, thickening the atmosphere, and creating a stable temperature regime for liquid water. However, research suggests that Mars simply doesn’t have enough easily accessible CO2 or other volatiles to generate a robust greenhouse effect.

Even if we used today’s technology to heat Mars, the lack of a global magnetic field remains a roadblock. Solar wind would continue stripping away any newly thickened atmosphere. Without a continuous process of atmosphere replenishment (like Earth’s volcanic or biological cycles), terraforming might be an ongoing battle rather than a one-time fix.

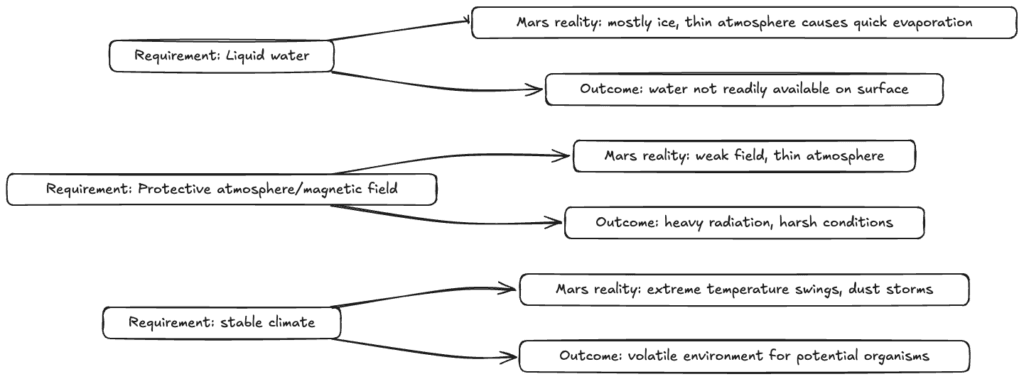

Life’s Fragile Recipe: Water, Stability, and Protection

When discussing “Why isn’t Mars teeming with life?”, it helps to revisit what life typically needs:

- Liquid Water: A solvent that enables chemistry to flow.

- Chemical Building Blocks: Elements like carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur. Mars has some of these, but not in the right states or concentrations for easy use.

- Energy Source: Sunlight or chemical energy. Mars gets sunlight, but dust storms and cosmic radiation complicate matters.

- Stability: Temperatures and environments that remain within tolerable ranges. Mars’s environment is too extreme and variable.

- Protection: A shield from harsh radiation, often provided by a planetary magnetic field or thick atmosphere.

Diagram: Requirements for Life vs. Mars’s Realities

Diagram: Contrasting what life needs vs. what Mars offers today

A Timeline of Martian Evolution

- 4.5 billion years ago: Mars forms from the solar nebula. It’s smaller than Earth but still experiences volcanic activity and possibly a global magnetic field.

- 3.7–3.5 billion years ago: The Noachian period—Mars is bombarded by asteroids, but also sees flowing rivers, lakes, and possibly an early ocean. Atmospheric pressure is higher, temperatures are milder.

- 3.5–3.0 billion years ago: The Hesperian period—volcanic activity wanes, atmosphere starts thinning, water bodies shrink or freeze.

- 3.0 billion years ago–present: The Amazonian period—Mars becomes the cold, dry desert we recognize, with sporadic volcanic eruptions, scattered ice deposits, and ephemeral signs of water flow in localized regions (like recurring slope lineae).

Each step in this timeline chipped away at Mars’s habitability. By the time large, complex life could have evolved (as it did on Earth), Mars was already locked in as a frigid desert with minimal atmosphere.

Could Ancient Life Have Thrived?

There’s a non-zero chance that microbial life once inhabited Martian lakes or subsurface aquifers. Researchers keep discovering new hints—like certain carbon isotopes or fleeting methane plumes. These signals might indicate geological or biological processes.

Still, these clues are ambiguous. Methane could be produced by chemical reactions between rock and water (called serpentinization) rather than by living microbes. Similarly, certain carbon signatures can have non-biological explanations. Thus far, no “slam dunk” proof exists that Mars was ever brimming with bacteria or algae. If life did emerge, it probably never got beyond the microscopic realm, and it may have perished once conditions turned hostile.

FAQ Section

Why do we think Mars once had water?

Satellite images show valley networks and outflow channels resembling dried-up riverbeds. Rovers have found minerals (like clays and sulfates) that form in liquid water. These lines of evidence confirm Mars had flowing water in the distant past.

Could there still be life underground?

Possibly. Underground regions may hold pockets of liquid brine or ice that melt periodically. In these sheltered environments, radiation levels are lower, and temperatures may be slightly higher. Researchers hope future missions will drill deeper to search for definitive signs of subsurface life.

How bad is the radiation on Mars?

Without a strong magnetic field or thick atmosphere, cosmic radiation and solar wind are significant. Measurements by the Curiosity rover show radiation levels that could be harmful over long periods, posing challenges for both microbial life and human explorers.

Is it feasible to terraform Mars in the near future?

Current studies suggest insufficient CO2 is readily available to create a robust greenhouse effect. Even if we managed to warm Mars temporarily, the lack of a global magnetic field means the solar wind can continue stripping away the atmosphere. Major breakthroughs would be needed to make terraforming a realistic endeavor.

Why is Mars colder than Earth, even though both are in the “habitable zone”?

Being in the habitable zone simply means a planet can theoretically host liquid water given the right conditions. Mars’s smaller size, thinner atmosphere, and lack of a strong magnetic field lead to rapid heat loss and low surface pressures, making it much colder than Earth.

Did NASA find definitive proof of Martian life with the Viking landers?

The Viking missions in the 1970s ran experiments that initially hinted at possible metabolism. However, most scientists now believe those results had non-biological explanations—chemical interactions with the perchlorate-rich soil. No consensus exists that Viking definitively detected life.

Why Are We Still Fascinated by Mars?

Mars has always been a mirror for humanity’s imagination. It’s close enough to observe in detail and shares some intriguing similarities with Earth—day length, polar caps, and historical evidence of water. If an alien planet next door did harbor life, it would dramatically reshape our understanding of biology, evolution, and our place in the cosmos.

Moreover, Mars remains our best candidate for manned missions beyond the Moon. Despite the planet’s hostility, it’s still more accessible than other potentially habitable worlds like Europa or Enceladus (moons of Jupiter and Saturn). With each rover that touches down, we edge closer to unveiling Mars’s secrets, hoping to find traces of past or present life.

Climate Change vs. Planetary Fate

People sometimes ask if what happened to Mars could happen to Earth—losing an atmosphere, drying up, and becoming lifeless. Earth, thanks to its robust mass, active geological cycle, and protective magnetic field, is unlikely to follow Mars’s path anytime soon. However, studying Mars’s fate does underline how precarious planetary habitability can be if key protective systems (like magnetic fields) fail.

Did Volcanic Activity Play a Role?

Volcanoes help recycle carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. During Mars’s early days, massive shield volcanoes like Olympus Mons (the largest volcano in the solar system) likely contributed to warming the planet. As Mars cooled internally and volcanic activity lessened, atmospheric replenishment slowed, hastening the planet’s transition into an arid state.

The Mystery of Martian Methane

Methane can be broken down quickly in the presence of sunlight or certain chemical processes. So, if we detect methane spikes on Mars, something must be generating it. Some possible explanations:

- Geological: Rock-water interactions known as serpentinization.

- Biological: Microbes releasing methane as a metabolic byproduct.

- Clathrate Release: Methane trapped in ice-like structures that occasionally vent to the surface.

None of these scenarios by themselves indicate a bustling ecosystem, but the presence of methane is intriguing enough to keep astrobiologists engaged. The fact that methane levels seem to vary seasonally also points to dynamic processes in the Martian subsurface.

Comparisons to Earth’s Early Microbes

Earth’s earliest known life forms were microbial, appearing around 3.8 billion years ago. These organisms flourished in oceans protected from harsh ultraviolet light, feeding on chemical gradients near volcanic vents or using sunlight. Mars may have once offered similar conditions but for a shorter duration.

If Martian microbes arose, they might have been forced underground as the atmosphere dwindled. Over time, these microbes would have had to adapt to severe dryness, high salt levels, and temperature extremes. The question is whether they survived or died off in the face of unstoppable planetary changes.

Potential Clues from Polar Ice Caps

Mars’s polar caps are made of water ice and frozen carbon dioxide (dry ice). In the winter, CO2 from the atmosphere condenses onto the poles, thinning the already meager atmosphere further. Beneath these polar layers could lie ancient ice that records climate changes over millions of years—like rings in a tree trunk.

Studying these layers might reveal episodes when Mars was slightly warmer or wetter. Such data could point researchers to times when microbial life had a fleeting chance to persist. NASA and ESA (European Space Agency) are keen on radar surveys and drilling missions to delve into these ice caps.

The Psychological Draw of Finding Even a Single Microbe

A common joke in astrobiology is that finding a single bacterium on Mars—no matter how tiny—would be as significant as discovering a city of aliens. The reason is that it would confirm life isn’t unique to Earth. Even if that life were extinct or very primitive, it would revolutionize biology.

The fact that we haven’t yet found that microbe, even with advanced rovers, strongly suggests no widespread biosphere remains on Mars’s surface. If life does linger, it’s hiding deep below ground or in microenvironments that rovers have yet to explore.

Mars vs. Other Potential Life Havens

When pondering why Mars isn’t teeming with life, it’s enlightening to compare it to other places in our solar system:

- Europa (Jupiter’s moon): Has a global ocean beneath an icy crust, likely more stable than anything on Mars today.

- Enceladus (Saturn’s moon): Geysers spew water vapor into space, hinting at a subsurface ocean.

- Titan (Saturn’s moon): Dense atmosphere, liquid methane lakes—exotic chemistry but definitely more robust than Mars’s environment in some respects.

Mars remains a priority for exploration because it’s a relatively easy neighbor to land on compared to the outer solar system. Still, icy moons may hold better chances for extant life than the radiation-baked surface of Mars.

Earth vs. Mars: The Basketball Analogy

If Earth is the size of a basketball, Mars is roughly a softball. That difference in diameter underscores why Earth can sustain plate tectonics, volcanoes, and a strong magnetic field for billions of years, while Mars cannot. A larger planet holds more internal heat, fueling the dynamo that maintains a magnetic field and volcanism. A smaller planet like Mars loses heat faster, its core solidifies or partially solidifies, and its global magnetic field shuts down.

Without a continuing cycle of atmospheric renewal and protection, any early habitability window on Mars was destined to slam shut far sooner than Earth’s.

The Volcano-Atmosphere Connection

Volcanic eruptions release gases like CO2, water vapor, and sulfur dioxide. On Earth, these emissions help regulate climate over geologic timescales, especially through interactions with oceans and life. Mars did have epic volcanic eras—Olympus Mons remains a colossal reminder. But once that volcanism declined significantly, so did the planet’s ability to replenish its atmosphere.

The relationship between a planet’s internal heat (which drives volcanism) and its surface conditions is a critical piece of why Mars fell behind in the “habitability race.” Earth, by contrast, remains geologically active, steadily reshaping its crust and outgassing materials that keep its environment relatively stable.

Human Exploration: Risks and Realities

If there’s no teeming life on Mars today, could humans eventually settle there and bring our own ecosystems? Possibly, but the challenges are enormous:

- Radiation: Astronauts on the surface would need robust shielding.

- Lack of Air: Mars’s air is mostly CO2 at extremely low pressure.

- Extreme Cold: Average temperatures around -60°C, plunging much lower at night.

- Toxic Dust: Perchlorates and fine dust that could damage lungs.

While a robotic outpost or research station is likely feasible, turning Mars into a “shirt-sleeve environment” like Earth seems far beyond current capabilities. Even if humans manage to build closed habitats and produce food in controlled environments, that’s not the same as Mars spontaneously sprouting forests or farmland.

Unfolding the Subsurface Secrets

Rovers and orbiters so far have mostly analyzed surface rocks and near-subsurface material. But we know that Earth’s deep crust harbors entire “deep biospheres” of microbes. There’s a chance Mars also has underground pockets where liquid water could remain stable, heated by residual geothermal energy or geochemical reactions.

Future missions—like the planned ExoMars rover from the European Space Agency—aim to drill deeper and look for biomolecules directly within subsurface layers. If we ever find Martian microbes, they might be living (or once lived) in these darker realms, shielded from the harsh surface environment.

Cosmic Perspective: Mars’s Significance

Even though Mars isn’t teeming with life, its story is crucial for understanding planetary evolution and the fragility of habitable conditions. By piecing together Mars’s puzzle, we learn more about how life might arise or falter in the universe. We also gain insights into exoplanets orbiting other stars—some might face similar fates if they lose their atmospheres or magnetic fields.

Mars teaches us that habitability is not guaranteed. A planet can start with the right ingredients but still fail to nurture a flourishing biosphere if key protective factors vanish. Earth appears exceptional in its longevity as a life-bearing world, at least in our solar neighborhood.

Summary: Why Isn’t Mars Teeming with Life?

- Atmospheric Loss: Mars’s magnetic field weakened, allowing solar wind to strip away much of its atmosphere.

- Thin, CO2-Dominant Air: Not enough pressure or greenhouse gas retention to sustain liquid water or moderate temperatures on the surface.

- Lack of Stable Water: Surface water evaporates or freezes quickly in the low-pressure environment, leaving no large bodies of liquid water.

- High Radiation: No magnetic shield means cosmic rays bombard the surface, a major barrier to life.

- Smaller Planet Size: Less internal heat, fewer volcanic eruptions, and a shorter-lived magnetic dynamo.

- Shorter Warm Period: Mars likely had a brief habitable window billions of years ago but has been cold and arid for most of its history.

No single factor alone dooms Mars to lifelessness, but the cumulative effect of these challenges results in a place where life—if it ever gained a foothold—struggled to hang on.

Read More

- The Case for Mars by Robert Zubrin (Amazon)

- Red Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson (fiction, but explores terraforming ideas) (Amazon)

- NASA’s Mars Exploration Program

- ESA’s ExoMars Mission

These resources explore the allure of Mars, the challenges of colonizing it, and the underlying science behind its transformation from a once more hospitable world to the barren landscape we observe today.