TL;DR: Plants are green because their main light-harvesting pigment, chlorophyll, reflects green wavelengths of sunlight rather than absorbing them.

Why Are Plants Green?

Why do plants wear their lush green costumes, blanketing fields, forests, and gardens in a signature emerald glow? If you’ve ever wondered why every blade of grass, leaf on a maple tree, or weed poking through a sidewalk crack shares this vibrant hue, the answer begins with photosynthesis—the process by which plants convert light energy from the Sun into chemical energy to power their lives.

In essence, the green color we see is the leftover light bouncing back into our eyes, while the more useful wavelengths are pulled in and used by the plant’s tiny energy factories. Chlorophyll, the star pigment, soaks up mostly red and blue light, reflecting green light back. This seemingly simple explanation unravels into a tale of evolutionary compromises, energy economics, and the interplay between plant biology and ancient atmospheric conditions.

Understanding the Light Environment

Light and the Solar Spectrum

The Sun showers Earth with a broad blend of electromagnetic radiation, from high-energy ultraviolet (UV) rays to the visible rainbow and into the infrared. Plants focus on photosynthetically active radiation (PAR)—mostly red and blue wavelengths. Our atmosphere also shapes what reaches the ground, filtering out some radiation and leaving a balanced spectrum that plants evolved to utilize.

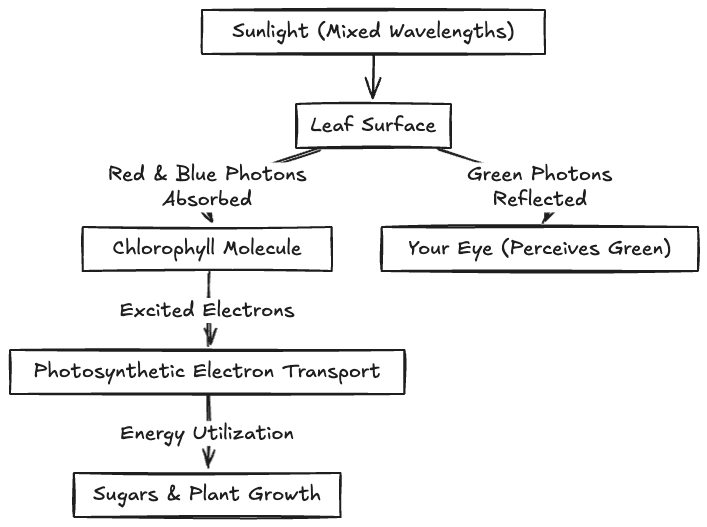

Chlorophyll: The Ultimate Green Pigment

Chlorophyll sits within chloroplasts, the plant’s miniature solar panels. It absorbs red and blue light efficiently, yet sends green light back out. To human eyes, leaves appear green, even though the plant is selectively absorbing and using other parts of the spectrum to build sugars and fuel growth.

From Photon to Sugar

When a red or blue photon hits chlorophyll, it boosts an electron to a higher energy level. This excited electron travels along an electron transport chain, ultimately helping to convert carbon dioxide and water into sugars. Green photons don’t fit this energetic lock-and-key, bouncing away and painting the world green.

Diagram: How Chlorophyll Absorbs Light

Evolutionary and Ecological Context

Why Not Absorb Green Too?

A longstanding question: Why haven’t plants evolved to use green light more effectively? Evolution often chooses “good enough” solutions. Chlorophyll’s stable structure and reliable performance at capturing red and blue photons might outweigh any benefits of altering its absorption profile. Reflecting green could also guard against energy overload, protecting delicate cellular machinery.

Evolutionary Legacy of Pigments

Ancient photosynthetic bacteria predate the chlorophyll we know today. Over billions of years, pigment systems evolved amid changing atmospheric conditions and competition. The green reflection may be a historical echo of evolutionary paths taken long ago, locked into place by the success of chlorophyll-based photosynthesis.

Alternative Pigments in Other Organisms

Algae, cyanobacteria, and other microbes have a rainbow of pigments, from reds to browns and golds. They evolved in different environments—dimmer waters, unique light conditions—and found evolutionary niches by capturing wavelengths that green plants neglect. This shows green is not the only path to photosynthetic success, just the dominant one on land.

Could Plants Be Another Color Elsewhere?

On distant worlds orbiting dimmer stars or with different atmospheric filters, photosynthetic life might favor other wavelengths. There, “plants” might be red, black, or purple, highlighting that our green vegetation is only one solution. Life can tune into starlight in various ways.

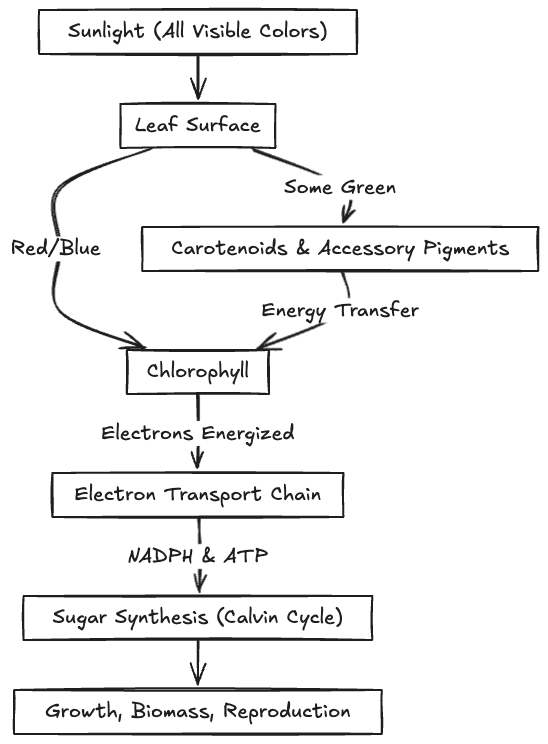

Fine-Tuned Biochemistry: The Role of Accessory Pigments

Plants don’t rely on chlorophyll alone. Carotenoids and xanthophylls broaden the usable spectrum and protect against energy overload. These accessory pigments pass captured light energy to chlorophyll or help dissipate excess energy safely.

Diagram: Energy Flow in a Leaf

Efficiency and “Wasted” Light

Reflecting green might seem wasteful, but nature values balance over perfect efficiency. Overly intense energy capture can harm photosynthetic systems. “Good enough” solutions—like primarily using red and blue—ensure stable, widespread success.

A Historical Perspective: Cyanobacteria and Beyond

Modern plants descend from ancient cyanobacteria, which harnessed light using a precursor to chlorophyll. Over time, these merged with other cells to form algae, and eventually terrestrial plants. The chlorophyll blueprint prevailed, passing through countless generations as Earth’s landscapes turned green.

The Sun’s Output and the Green Gap

The Sun emits lots of energy in the green-yellow range. Yet plants leave much of this color unused. One hypothesis is that early photosynthetic organisms adapted to specific niches, and by the time green plants rose to dominance, the chlorophyll system was deeply entrenched.

If Earth Were the Size of a Basketball…

If Earth were a basketball, the green plant layer would be like a thin layer of paint—a fragile film that, despite its delicacy, sustains entire ecosystems. This perspective shows the astonishing efficiency of green photosynthesis at a planetary scale.

The Biochemistry of Absorption: A Closer Look

Chlorophyll’s structure—a porphyrin ring with a magnesium ion—perfectly supports red and blue absorption. Absorbing green light would require altering the pigment’s electronic structure, potentially destabilizing a finely tuned system.

Human Perspective and Vision Bias

Human eyes evolved to detect green well, as plants became central to our food and environment. To us, plants appear green, but other creatures with different vision systems might see leaves in unfamiliar ways. Our interpretation of “green” is partly about our own biology.

Myth-Busting

Myth: More Green Light Means Healthier Leaves

A greener leaf isn’t always healthier. Leaf color can shift with nutrient availability, sunlight intensity, and seasonal changes. The relationship between greenness and health is more nuanced than the simple “more green = better” assumption.

Myth: Autumn Colors Are a Sign of Plant Failure

When leaves turn yellow, orange, or red in autumn, it’s not failure—it’s strategy. Plants break down chlorophyll to reclaim nutrients, revealing vibrant accessory pigments. The leaf drop is a controlled, beneficial process to prepare for winter dormancy.

Myth: All Plants on Earth Are Green

Most land plants are green, but not all. Some ornamental plants carry purples or reds. Parasitic plants lack chlorophyll altogether. In oceans, algae range in shades beyond green. So, while green dominates, nature’s palette is wider than you might think.

The Future and Further Inquiries

Could Genetic Engineering Make Plants Less Green?

Biologists could theoretically engineer pigments to broaden absorption. But the risk is destabilizing a proven system. Evolution locked in chlorophyll for a reason: it works. Radical changes might lead to unintended consequences, so don’t expect red forests soon.

An Energetic Puzzle Yet Unsolved

Scientists still debate the precise reasons plants reject green photons. Multiple factors—evolutionary history, ecological competition, biochemical stability—likely intertwine. Ongoing research, from quantum chemistry to genetic studies, seeks definitive answers.

Lessons from Nature’s Design

Green leaves reflect a balance between capturing energy and maintaining stability. The billions of years it took to refine photosynthesis show that nature doesn’t chase perfection—it pursues sustainability. The green world is proof that “good enough” can reshape a planet.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are plants green because they contain chlorophyll?

Yes. Chlorophyll absorbs red and blue light, reflecting green, which is why plants appear green.

Do plants absorb any green light at all?

They do absorb some green photons, but less efficiently than red or blue. Accessory pigments help capture a portion of green light, though much is still reflected.

If plants reflect green light, does that mean they waste energy?

Not necessarily. Plants balance energy capture and stability. Too much absorption could damage the photosynthetic apparatus, so reflecting green light is part of maintaining a steady, effective system.

Can plants evolve to absorb green light better?

It’s possible in theory, but chlorophyll-based photosynthesis is already highly successful. Altering fundamental pigments would require major biochemical changes that may not yield evolutionary advantages.

Why do some plants have red or purple leaves?

These colors often come from accessory pigments like anthocyanins. Such pigments can serve protective roles against intense light or help deter herbivores. The green chlorophyll is still there, just overshadowed.

Are there places where green is not the dominant color of photosynthetic life?

Yes. In marine environments, red and brown algae, as well as cyanobacteria, thrive using different pigments. Conditions like water depth, temperature, and available nutrients shape their coloration strategies.

Does the Sun’s spectrum influence plant color?

Absolutely. Earth’s sunlight and atmospheric conditions steered the evolution of chlorophyll-based photosynthesis. A different star or planetary atmosphere might favor other pigments, producing forests of entirely different hues.

Can artificial lights change the color of plants?

Certain grow lights emphasize red or blue wavelengths, influencing leaf pigment concentration. While you won’t easily make plants non-green, tailored lighting can shift leaf coloration and affect growth patterns.

Read More

- “Photosynthesis” by David Walker (Amazon)

- “Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis” by Robert E. Blankenship (Amazon)

- “Life Ascending: The Ten Great Inventions of Evolution” by Nick Lane (Amazon)

- USDA Agricultural Research Service

- Journal of Experimental Botany for insights into current plant physiology research.